Mariners in the New Orleans area quickly become familiar with the traffic controls at the sharp and heavily trafficked bend in the Mississippi River at Algiers Point, Mile 94.5 AHP. The Governor Nicholls Street Wharf Traffic Control Light, or “Governor Nick” as it’s known, has been controlling traffic at the point for as long as probably any mariner alive today can remember.

But Governor Nick was not always there. Well into the 20th century, river pilots approaching Algiers Point had to keep a watchful eye on the horizon and look for a telltale masthead light above the trees and houses in Algiers.

It was a bad place to have to make quick changes in course and speed, especially during high water. A couple of pre-Governor Nick incidents can help illustrate the dangers.

C.H. Ellis/Galicia

The brand-new steamship C.H. Ellis arrived in New Orleans in the summer of 1904. A shipyard in Bergen, Norway, built the ship for the United Fruit Company, and sent it, ballasted, across the Atlantic. Although it sailed from Norway with no revenue cargo, it stopped at Puerto Limón, Costa Rica, to take on 30,000 bunches of bananas.

The Ellis arrived in New Orleans on June 30 to a loud and raucous welcome, virtually all the boats in port sounding their whistles for the shiny new entry in the Central American fruit trade. Local U.S. inspector Kelly and two assistant inspectors boarded the next day, and found the new ship to be in good condition and fully in compliance with all the requirements of the current marine statutes.

After a day and an evening of preparation and partying, the Ellis got underway from one of the fruit wharves just above Canal Street at 9:30 p.m. on July 2.

Capt. Hansen and pilot Robert Plant were on the bridge. The Ellis was once again ballasted down, there being no outbound cargo for the voyage to Colón, Panama. There was still a party atmosphere on board, with prominent passengers along for the ship’s first sailing out of New Orleans.

By about 10 p.m., the Ellis had topped around and was coming down on the Canal Street ferry crossing. One of the ferries was crossing to the Algiers side. The two vessels exchanged signals and Plant ordered the engines slowed. Once the ferry had crossed their bow, Hansen and Plant saw the masthead light of an upbound steamship below Algiers Point. Hansen ordered the engines stopped.

The upbound vessel was the Hamburg-American liner Galicia, with general cargo out of Hamburg, Germany. Capt. Hauer was down below, and pilot Schmidt was on the bridge as the Galicia appeared around the point. The Ellis blew one whistle, and the Galicia answered in kind. The Ellis proceeded one quarter speed ahead. Unfortunately, the Galicia swung around and ended up steering straight at the Ellis under full speed

Both ships backed down, but it was too late. The Galicia struck the Ellis hard on the port side about 50 feet aft of the bow, shearing hull plates from the main deck down to at least the water line.

One of the crew quarters in the forecastle was split in half, sending four crew members scrambling out of their bunks. In the confusion, one of the cooks on the Ellis, badly injured, actually ended up on the Galicia while the two ships were still in contact. He had to be reunited with his shipmates the next day.

During the lowering of the Ellis lifeboats, two passengers fell in the river and had to be retrieved. Meanwhile, the Ellis was starting to go under. The distress signal was sounded, but Hansen and Plant didn’t wait for tugs. They went full ahead and hard right to round up and drive the sinking ship onto the mud below Algiers Point. The bow deck was awash by the time the Ellis plowed into the bank between the wooden drydocks and the Algiers sawmill right below the point.

The tugs El Vivo and W.G. Wilmot were soon alongside, catching lines to keep the ship from sliding into the deep water off the point. At midnight, three more tugs were called, as well as a diver. It was well into the following evening before the pride and joy of the United Fruit Company fleet was stabilized and bulkheaded and very carefully towed to the new U.S. Navy drydock just downstream at the Algiers naval facility.

Right after the collision, the Galicia had continued under its own steam up to the Southern Pacific Railroad dock in Gretna, damaged but not in danger.

Kleber/Hugoma

Not quite three years later, another collision at the point involved yet another noteworthy ship whose arrival was eagerly awaited. The French Navy warship Kleber was an armored cruiser launched in 1902. It was paying a courtesy call, but became part of what was described then as “one of the most exciting and thrilling disasters in the history of the harbor of New Orleans.”

The river was high when the warship approached Algiers Point upbound on the evening of February 20, 1907. Capt. de St. Pern and pilot Patrice Arroyo were on the bridge, as was Adm. Albert Thierry, commanding officer of the French Atlantic fleet.

In the meantime, the freighter Hugoma had gotten underway from the Stuyvesant Docks, across the river from Harvey Lock, beginning a voyage to Puerto Rico. Captain Richard W. Lewis and pilot William F. Short were on the bridge, and the freighter headed down toward Algiers Point.

The collision happened at 7:15 p.m. As the Hugoma came abeam the fruit docks above Canal Street, and the Kleber started coming up around Algiers Point, the ferry Josie started crossing from Algiers to Canal Street. After proper signals and a safe crossing by the ferry, there was a confusion of signals between the two ships. The downbound freighter went for one whistle, but the upbound cruiser went for two.

Danger signals and full-astern orders notwithstanding, the sharp bow of the French cruiser hit the Hugoma’s port side, just aft of amidships, nearly slicing the freighter in two. The freighter began sinking so quickly, there was no time to lower lifeboats. Crew members jumped overboard, lastly Capt. Lewis—because he was the captain, but also because he couldn’t swim.

The Hugoma was carrying general cargo. The deck cargo consisted of almost 5,000 creosoted railroad ties, intended for a new railroad in Puerto Rico. Many of the wooden ties broke free, and they served as flotation devices for the crew in the water. Tugs scrambled to the scene, and all of the crew were rescued.

While the cruiser Kleber escaped with a few dents on the bow, the Hugoma sank in 120 feet of water.

The commander and pilot of the Kleber testified that they had blown two whistles, and that the Hugoma had improperly responded by blowing one whistle. There were suggestions that the pilot on the Hugoma may have been confused by the cacophony of horns and whistles and bells throughout the harbor welcoming the French warship.

U.S. inspectors Benjamin Kelly and Cecil Bean concluded otherwise. Their decision on March 14 was that the Hugoma had properly and successfully exchanged one-whistle signals with the ferry Josie, then had blown one whistle for the Kleber. The inspectors said that the Kleber had improperly responded with two whistles and, in violation of the Western Rivers pilot rules, steered to meet starboard-to-starboard. Kelly and Bean held “said cruiser Kleber to be entirely at fault.”

But it could be asked, why have a loaded steamship come barreling downstream during high water and at the same time have a foreign ship of war arrive with all the boats in the harbor blowing their whistles?

The answer is that there was no notion back then of vessel traffic control telling you when and where to meet—only a requirement to follow the pilot rules when you do happen to meet. Those days would eventually fade away, as traffic increased and steamships got bigger and heavier.

By the 1930s, traffic at Algiers Point was increasing noticeably. In October 1931, for instance, 193 ocean-going vessels arrived in port, and 200 departed. That translates to about a dozen ship movements per day, but the traffic situation was complicated by growing inland traffic from the new Intracoastal Waterway and other routes. That month, 1,362 vessels transited the new Industrial Lock, an increase of 733 compared to a year earlier. Overall there were 388 inland vessel arrivals at the Port of New Orleans in October 1931, a more than 200 percent increase over the previous October.

In February of 1932, a conference was called by R.A. Stiegler, superintendent of docks at the Port of New Orleans. The meeting included towboat captains, river pilots and steamship representatives. The conference of mariners brainstormed and debated, and came up with the idea of managing traffic at Algiers Point by erecting towers with some sort of signals, perhaps at Barracks Street opposite the point, and perhaps at Gretna in the vicinity of Gouldsboro Bend. Steigler said that the committee would make a careful study “as to the visibility of signals from such towers in foggy weather, to safeguard navigation with a minimum of interruption.”

New Signals

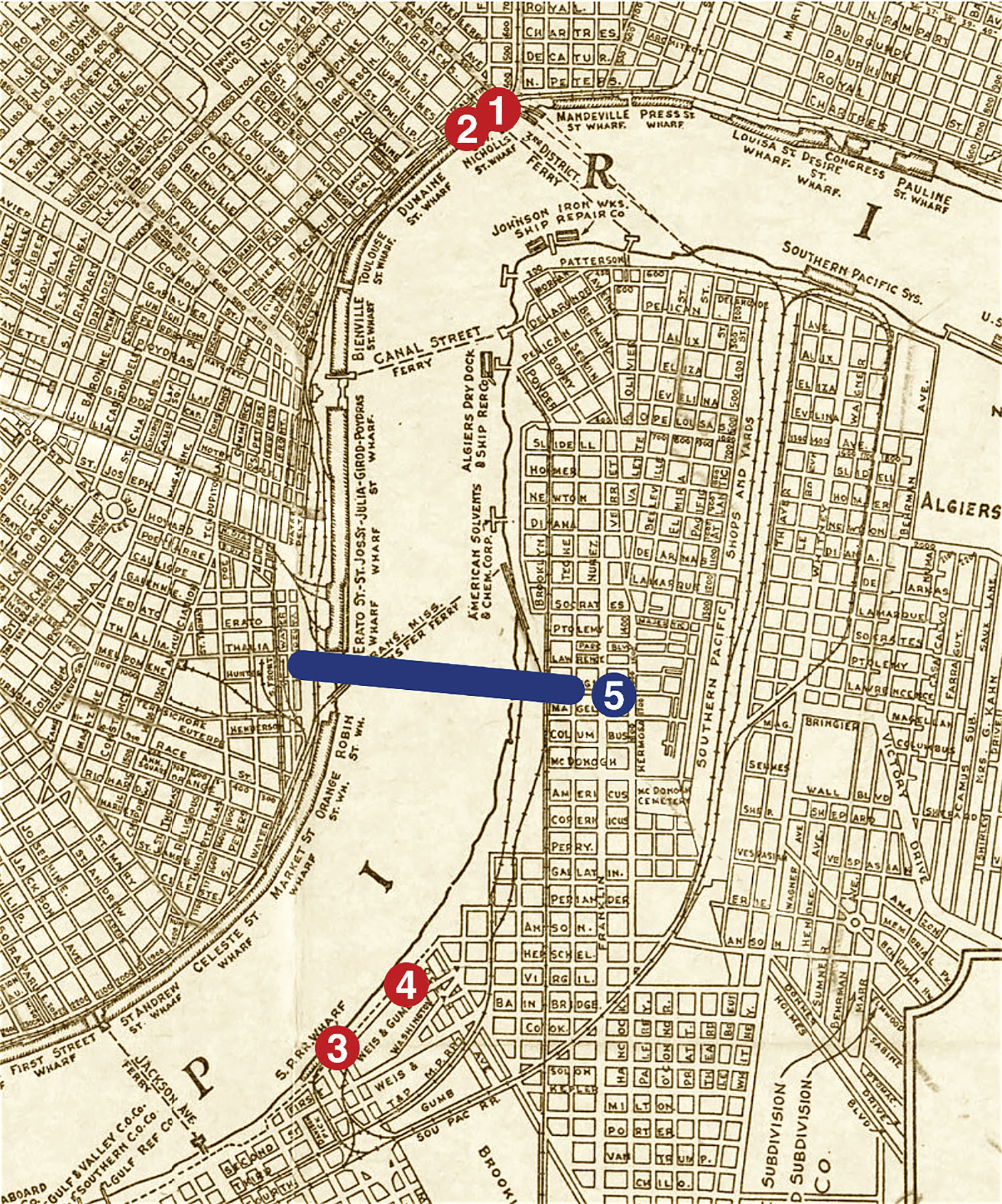

The mariners’ committee worked fast. They came up with a system of signals and arranged for the cost to be shared by the Dock Board and the Crescent Pilots. The plan was to build signal towers at Barracks Street Wharf (Mile 94.3L AHP) and at the Southern Pacific Railroad dock in Gretna (Mile 96.8R AHP, at the upper end of today’s John W. Stone Oil dock, just above the Gretna water intake).

The Crescent Pilots would operate the signals. In those days, the Crescent Pilots’ territory included the harbor above Algiers Point. The NOBRA Pilots were a limited group of no more than nine pilots, mostly engaged in piloting tankers to and from the Standard Oil refinery in Baton Rouge.

By the first week of March, makeshift towers had been constructed at both locations. They were more like scaffolds, with pulleys to hoist signals up by hand. Six Crescent pilots were assigned—Pettigrove, Loga and Morrissey at Barracks Street; and Vogt, Hansen and Hanley at Gretna. They would work eight-hour shifts, around the clock during high water.

The signals themselves at each location consisted of two white lights, plus two black balls for daytime use. The balls were 5 feet in diameter, made out of wire with painted canvas around the outside.

One black ball would indicate that Algiers Point was clear for a descending vessel. Two balls, one above the other, 8 feet apart, meant Algiers Point was clear for an upbound vessel. At night, lights replaced the balls in the same configuration, each flashing for two seconds with an interval of two seconds. The absence of signals, day or night, was to be considered a danger signal.

A pilot scheduled to leave any wharf in the harbor and intending to navigate the river between Julia and Desire Streets (including Algiers Point) was required to telephone the Barracks Street tower man before sailing.

The Barracks Street and Gretna traffic signals were first used at 7 a.m. Sunday, March 6, 1932. The installation was somewhat primitive, but it was apparently the first such waterway traffic control system anywhere.

Local harbor interests—pilots, other mariners, the Dock Board and shipping companies—had taken the initiative to create a traffic control system. Within a few months, though, the Army Engineers got involved, planning an improved system and drawing up navigation regulations. By the spring of 1935, they had installed improved towers with red and green lights to replace the single and double white lights. Manning of the traffic lights by river pilots continued, but under the aegis of the Army Engineers.

Traffic control at Algiers Point changed very gradually over the years. In 1947, the Barracks Street tower was rebuilt and relocated 250 feet upriver, atop the Governor Nicholls Street Wharf. The Gretna light moved from atop the Southern Pacific wharf to to a new location on the levee, a couple of city blocks downriver. And a repeater light was installed upriver at Westwego, to give downbound ships advance warning of a red light at Gretna.

By the early 1970s, use of radar and VHF marine radio had become standardized. Mariners could talk to the watchstander on the radio in addition to looking for the red or green light. Since “Governor Nicholls Street Wharf Traffic Control Light” is quite a mouthful to be repeating on the radio, it wasn’t long before the Algiers Point light and its pilot-operator acquired the nickname “Governor Nick.”

By the late 1970s, the traffic lights had come under the purview of the U.S. Coast Guard, rather than the Corps of Engineers. This dovetailed with the Coast Guard’s voluntary vessel traffic service (VTS) of the 1970s and 1980s. That VTS didn’t last, but the traffic lights remained under the umbrella of the Coast Guard.

By 2010, the Algiers Point traffic control operation was being incorporated into the Coast Guard’s new, mandatory VTS.

Mariners underway at Algiers Point have quite a few tools at their disposal today that weren’t available to the pilots and the Dock Board back in 1932, including radar, GPS, AIS and VTS. But on top of all that, they have the experienced eye and familiar voice of “Governor Nick.”