This coming December 7, in addition to being Pearl Harbor Day, is the 50th anniversary of one of the worst tragedies in U.S. Coast Guard history—the sinking of the 133-foot cutter White Alder in the Lower Mississippi River, with the loss of 17 crewmembers.

The White Alder was one of a fleet of buoy tenders that began their careers as U.S. Navy freight and ammunition carriers. During World War II, the Navy needed shallow-draft vessels to transfer materiel between seagoing ships and shallow ports. The design they came up with was 133 feet long, about 30 feet wide, and with a draft of less than nine feet. The twin-screw diesel vessels would have open cargo decks, and built in cranes or lighters to transfer heavy cargo.

During the war, American shipyards were so busy that the Navy had to search far and wide for fabrication yards to produce these vessels. They settled on three small companies in different parts of the country. One was a yard in northern California that had only produced unmotorized barges. Another was a cement and steel fabrication yard in Erie, Pa., that had never produced a floating object of any kind.

But the future White Alder was built at an actual shipyard, Niagara Shipbuilding in Buffalo, N.Y. Hull number YF-417 was launched there in 1943.

After the war, the Coast Guard was looking for vessels to augment its buoy- tending capability. The YF boats looked ideal. The same characteristics that made them useful to the Navy—shallow draft, with an on-board lifting mechanism—made them almost tailored to placing heavy buoys in shallow waterways.

The Coast Guard acquired eight YFs, made some modifications, and named them each for a plant, shrub, or tree beginning with the word “White,” such as White Sumac, White Holly, and White Sage.

The Navy’s YF-417 became the Coast Guard’s White Alder. After some shipyard time, including replacing the electric hoist arrangement with a stronger A-frame with hydraulic power, the new buoy tender was stationed at New Orleans. In addition to taking care of buoys and lights, the White Alder became a fixture in port, and a reliable presence for mariners in the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast area.

Among the alternative jobs the buoy tender found itself doing, in 1948 the White Alder was dispatched to South Pass after a knife fight broke out on a Lykes freighter. An injured crewman was transferred to the White Alder for medical treatment.

In 1954, the White Alder was one of four boats battling the fire that destroyed part of the Southern Railway bridge over the Rigolets.

During Mardi Gras season in 1955, when a small airplane crashed in Lake Pontchartrain, the White Alder grappled it off the bottom and hauled it on deck. It wasn’t the first time. Three years earlier, the White Alder had salvaged a downed U.S. Navy Bearcat fighter plane in the same area.

Later in 1955, the White Alder evacuated three or four Coast Guardsmen from the Point au Fer light station to Morgan City when Tropical Storm Brenda approached.

But more often than not, the crew of the White Alder were busy maintaining aids to navigation, servicing lights, repairing light structures, replacing buoys, and bringing buoys back to base for repair and refurbishing.

In July 1950, the White Alder was under the command of Chief Warrant Officer Ulmer Crooke Wilson, servicing and replacing Cat Island 1 and 7 and other buoys at Marianne Channel in the Mississippi Sound. The newest member of Wilson’s crew was apprentice seaman Robert J. Clark, whose job description then was “galley boy.” Clark bragged about the job, saying, “Chow’s good. Meat two times a day. Hell, they got to feed a ship like this. This is the working end of the Coast Guard.”

December 1968

In December 1968, the White Alder, with Chief Warrant Officer Samuel Brown in command, was sent out on Lake Pontchartrain again. Their job this time was to help another buoy tender, the Loganberry, which had run aground. Brown and his crew successfully floated the other cutter on December 4. The last photograph taken of the White Alder was an aerial shot on Lake Pontchartrain right after completing the job.

The White Alder then prepared for a more routine task, retrieving low-water buoys on the Lower Mississippi River. The cutter got underway from Base New Orleans at 6:34 p.m. on December 6, transited Industrial Lock, and headed upriver. The crew sent messages shortly after midnight and then just before 8 a.m on the 7th to report progress on retrieving buoys. They finished their assignment that afternoon at Red Eye Crossing, just below Baton Rouge.

The last message received from White Alder was at 4:25 p.m. on the 7th, giving an estimated time of arrival back in New Orleans of 9 a.m. the following day. The crew had stowed three lighted buoys and 19 unlighted buoys on deck, and were downbound, headed home. Commanding officer Brown and seaman Roger Jacks were on the bridge. Many of the crew were in their bunks.

Meanwhile, the 455-foot Taiwanese freighter Helena was upbound for Baton Rouge. NOBRA pilot Harold Rowbatham was on board and on the bridge, along with the ship’s third mate, helmsman, and lookout. The ships’ captain, Shih Teh-Chang, was down below eating dinner. Rowbatham was carrying a handheld VHF radio tuned to channel 13. There were two radar sets. One was in standby mode, and the other was not operational. Rowbatham was not using radar.

The ship was high in the bow, drawing seven feet forward and 21 feet aft. There was no bow lookout.

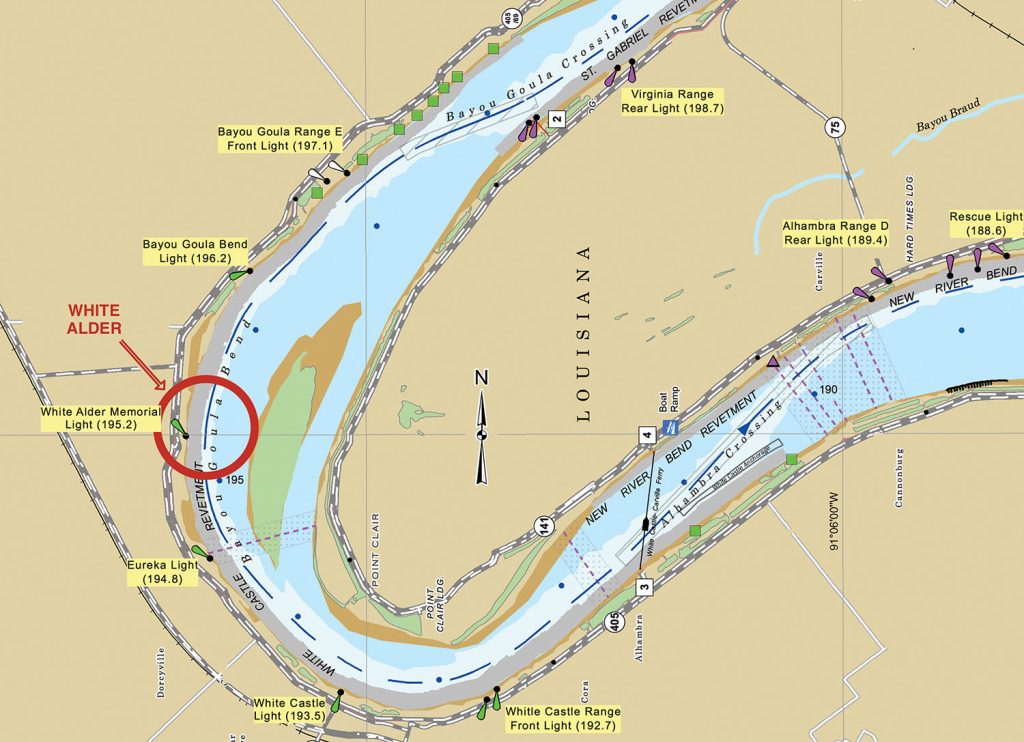

At 6:14 p.m., the Helena was near Mile 192 AHP, just below Bayou Goula Bend. The ship entered the bend at full speed, making 14 mph. over the bottom. The river stage at New Orleans was about 5 feet on a slow rise. The speed of current at Bayou Goula Bend was estimated at a little more than 3 mph.

At 6:22 p.m., a red light with a white light over it were sighted just off the ship’s starboard bow. Rowbatham sounded one long blast, but received no reply. He tried calling the unidentified vessel on his handheld, but still with no reply. He and the ship’s crew observed the lights for about four or five minutes and saw them cross to their port bow. So far it looked to them like a perfectly normal one- whistle meeting situation.

At 6:27 p.m., the lights suddenly showed green with white over, and the lights were now moving toward Helena’s starboard bow. Rowbatham went out onto the ship’s port bridge wing to try to see the vessel. At 6:28 p.m. Rowbatham heard a four-whistle danger signal from the vessel, so he ordered the engines stopped.

At 6:29 p.m., at Mile 195.6 AHP, the two vessels collided.

On the White Alder, boatswain’s mate Richard Kraus was in his bunk, on the port side, main deck, about midships. He heard the four whistles, and almost immediately there was a collision. The impact tore his bunk loose, throwing it forward and knocking him to the deck. The lights went out, the cutter listed to port, and the crew compartment rapidly took on water. Kraus managed to fill his lungs with air, make his way through the forward passageway, and swim to the surface. He swam to one of the buoys that had broken free from White Alder’s deck.

Fireman Bruce Kopowski was playing cards in the mess area with some other shipmates when he heard the danger signal. He started to get up but was knocked down by the force of the collision. The forward bulkhead of the mess deck collapsed, and the compartment started filling with water. Kopowski struggled clear and made his way to the surface. He swam to the same buoy, and Kraus helped him aboard.

Apprentice seaman Lawrence Miller was getting ready to wash dishes in the galley, on the starboard side of the main deck. He heard the four blasts, and men yelling, “Get off the ship!” The impact almost knocked him to the deck, but he held onto the sink and was scalded by hot dish water. River water rushing in knocked him around, and he was disoriented in the dark, but he found an air pocket, filled his lungs with air, and was able to swim to the surface where he found a ring buoy. He looked one way and saw the White Alder’s bow barely sticking up out of the water. In the other direction he saw Kraus and Kopowski on the drifting buoy.

The White Alder sank within about a minute. Kraus, Kopowski, and Miller and their buoy drifted downriver and grounded on the west bank near Mile 194.5 AHP. They were picked up by a Corps of Engineers vessel at about 7:10 p.m. They were transferred to ambulances aboard the White Castle ferry Feliciana, and brought to a hospital. The other 17 crew members were missing and presumed dead.

Searches were made downriver, but there was little doubt that they were all inside the cutter below.

Salvage Attempts

The wreck of White Alder was located at about Mile 195.2 AHP, lying sideways in the channel with the bow pointing toward the west bank. A Corps of Engineers survey boat marked the site with two wreck buoys. The Coast Guard prepared for diving operations to attempt to recover the bodies. Navy divers were flown in from Florida, and on December 9, they, along with Coast Guard scuba divers, began operations. Because of the strong current, they were unsuccessful.

On December 12, an outside diving contractor began operations. By connecting themselves to a 250-pound descending weight, they were able to reach the wreck. Their mobility was severely restricted, and they could only operate in a radius of about 15 feet of the weight.

On December 14, the divers recovered the body of Seaman Roger Jacks from the wheelhouse. The next day, they were able to recover the body of the skipper, Samuel Brown. The divers’ movement inside the wheelhouse was severely restricted, but they were able to determine that the cutter’s rudder indicator was showing approximately 10 degrees right rudder, and that the engine control levers were in about one-third speed ahead position.

Meanwhile, the strong current flowing around the sideways vessel had caused scouring action immediately downstream, creating a deep hole. On December 17, the wreck shifted, dropping into the hole. The shift caused severe turbulence, and the wreck buoys disappeared. The turbulence subsided after about 24 hours, and divers began operations again. It wasn’t until December 20 that they were able to locate the wreck again. They found that White Alder had dropped more than 30 feet below the river bottom, and that the only part of the boat sticking up out of the bottom was the upper 10 feet or so of the A-frame.

Most of us who have worked on the Mississippi River have learned to have a healthy respect for its awesome power, but this was Old Man River at his cruelest. Once the venerable buoy tender was on the bottom, the river had literally dug a hole for it, then pushed it into the hole, then covered it up.

All diving operations ceased. Between December 30, 1968, and January 2, 1969, there were attempts to somehow sweep wires under White Alder’s hull, to try to raise it enough to drag it to the bank. This was completely unsuccessful. By this time, White Alder was encased in what one diver called “hard-packed sand.”

There was no choice but to leave the bodies of the 15 remaining crew members where the river put them. They remain there to this day.

Investigation of the accident proved problematic. The men at the helm of the White Alder did not survive to explain what happened. The Coast Guard and the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) listed probable causes, including the Helena pilot’s failure to slow down or stop as soon as the meeting situation didn’t look right, but also simply the White Alder’s sudden and unexplained change of course at the last minute, crossing the Helena’s bow.

The NTSB criticized the investigation process, including the problem of having a government agency investigating an accident involving one of its own vessels, as well as the failure to do post-mortem examinations of Brown and Jacks, which could have shed light on whether an unexplained disability may have affected the vessel’s operation.

For its part, the Coast Guard, after the loss of White Alder along with the loss of two other cutters in 1978 and 1980, moved the agency to make improvements in cutter policy, doctrine, training and standardization.

Memorials

There are at least three White Alder memorials. The light at Mile 195.2 AHP, between Bayou Goula Bend Light and Eureka Light, was renamed White Alder Memorial Light. And there is a memorial to the White Alder and crew at the USS Kidd museum in Baton Rouge.

The Coast Guard dedicated a memorial to White Alder and crew at Coast Guard Base New Orleans on the first anniversary of the collision. The memorial consists of one of the buoys from the deck of White Alder, marked “WA,” with a light that flashes 17 times. The memorial was moved to the new Coast Guard Group New Orleans location on Lake Pontchartrain and rededicated in December 2002.

At the rededication in 2002, 8th Coast Guard District commander Rear Adm. Roy Casto noted that he had served aboard the White Alder for four months as a Coast Guard Academy cadet. He recalled that he was “impressed with the way the White Alder’s crew worked so well as a team to horse the 8-foot by 26-foot, 12,000-pound buoys on deck, repairing them and then returning them to the water, properly ‘winking and blinking.’ It was back then that I first decided I was going to work toward getting a buoy tender as my first duty station when I graduated the Academy, a goal I was fortunate to achieve a year and a half later.”

To the uninitiated, a legacy of buoy-tending might sound undramatic or unheroic. But any experienced mariner on the waterways would likely counter that a day rarely goes by when his or her work, livelihood, or safety does not hinge in some way on the work of the buoy-hoisting, barnacle-scraping aids-to-navigation crews. Or, as White Alder crew member Robert Clark put it in 1950, “the working end of the Coast Guard.”

White Alder Crew List

CASUALTIES: SA Walter Abbott III, EM2 Michael Agnew, CWO Samuel Brown, SN Frank Campisano III, FN Maurice Cason, QM2 John Cooper Jr., SN Richard Duncan, SA Larry Fregia, SA Ramon Gutierrez, SN Roger Jacks, SN Steven Lundquist, YN2 Joseph Morin, CS2 Charles Morrison, EN3 Walton O’Quinn Jr., EN1 John Rollinson, ENC William Vitt, BM3 Guy Wood.

SURVIVORS: BMC Richard Batista (on shore leave), FN Bruce Kopowski, BM2 Richard Kraus, SA Lawrence Miller.