On the Mississippi River and the other navigable waterways of the United States, the transition from steam to diesel power was a decades-long process that took up most of the first half of the 20th century.

Business and science writers in the second decade of the century wrote glowingly of the coming high-tech future of propulsion by internal combustion. In the 1920s, American diesel pioneer Clessie Cummins was writing educational articles in The Waterways Journal describing how diesel engines work. In the 1940s, the pages of the Journal were peppered with articles and advertisements about old steam towboats being repowered with diesel engines.

But the pioneers of diesel power on rivers and canals began a little bit earlier—and not on American waters, but on the barge canals and rivers of Europe. In 1903, engineers working separately in France and in Russia launched self-propelled barges with innovative diesel power plants, and put them to work.

Two French engineers, Frédéric Dyckhoff and Adrien Bochet, had worked together since 1899 and had installed gas and kerosene engines in canal boats with some success. Dyckhoff was a friend of Rudolf Diesel himself, and was his first licensee.

Dyckhoff and Bochet came up with an engine specifically designed to avoid unbalanced impacts on the hull of a small vessel. Their earlier internal combustion engines had caused hull failures in shallow-draft self-propelled wooden barges.

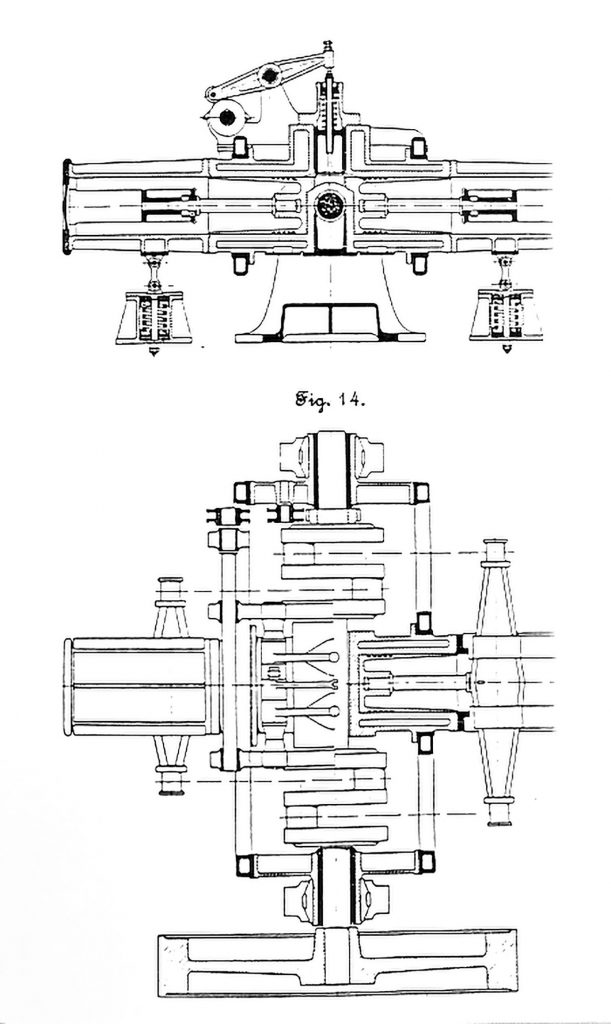

The solution was a horizontal, opposed-piston design, adapted from an earlier gas engine that the two engineers had patented. In this unique configuration, the axes of the single cylinder and the crankshaft intersected at a right angle midway along the crank throws. There were two pistons, each pointing toward the other in the same cylinder. The single combustion chamber serving both pistons was a connecting passage over a tunnel through which the crankshaft passed. The engine had a 210- by 300-millimeter bore and stroke (for each piston). It developed 25 bhp. at 360 rpm.

The engine was produced by Bochet’s company, Sautter Harlé, at their shop in Paris. The company also produced Fresnel lenses for lighthouses, among other marine navigation products.

The typical self-propelled barges on the French and Belgian canals of the period were 126 feet long and 16 feet wide, with a 6-foot draft. They barely cleared the locks on the Marne-Rhine canal in northeastern France. The waterway was not quite 200 miles long, but there were 178 locks.

The barge selected for the historic diesel installation was the Petit Pierre. It was a single-screw with reversible propeller blades. The engine itself was not reversible.

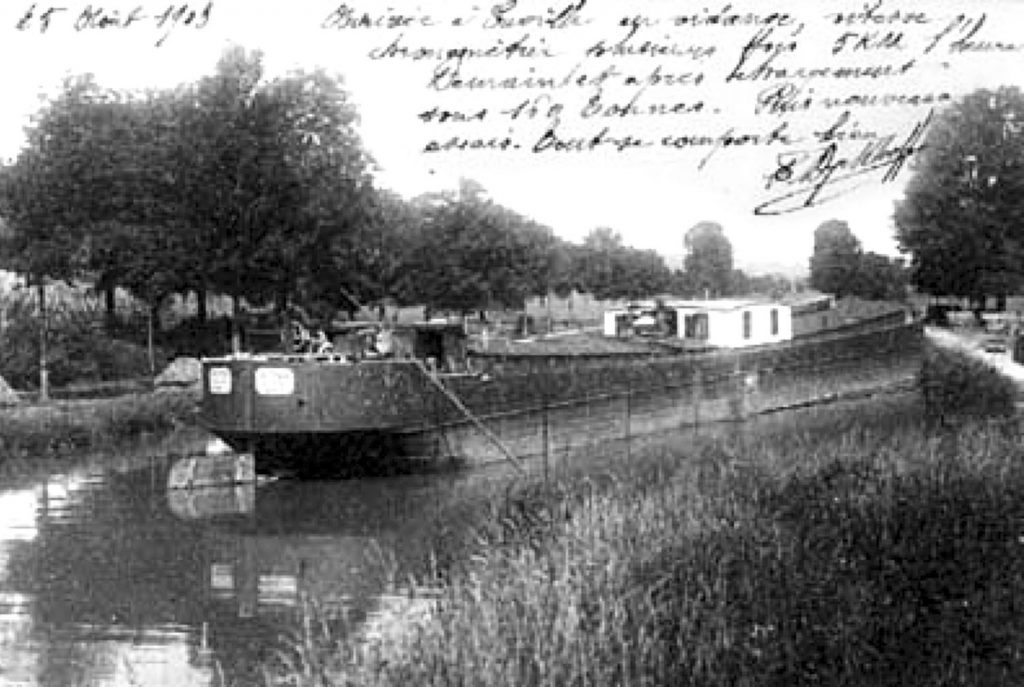

The 7-mile maiden voyage took place on September 30, 1903. It was enough of a success that Dyckhoff sent a picture postcard to Rudolf Diesel describing the performance. On October 25, Diesel visited and was treated to a day trip on the Petit Pierre.

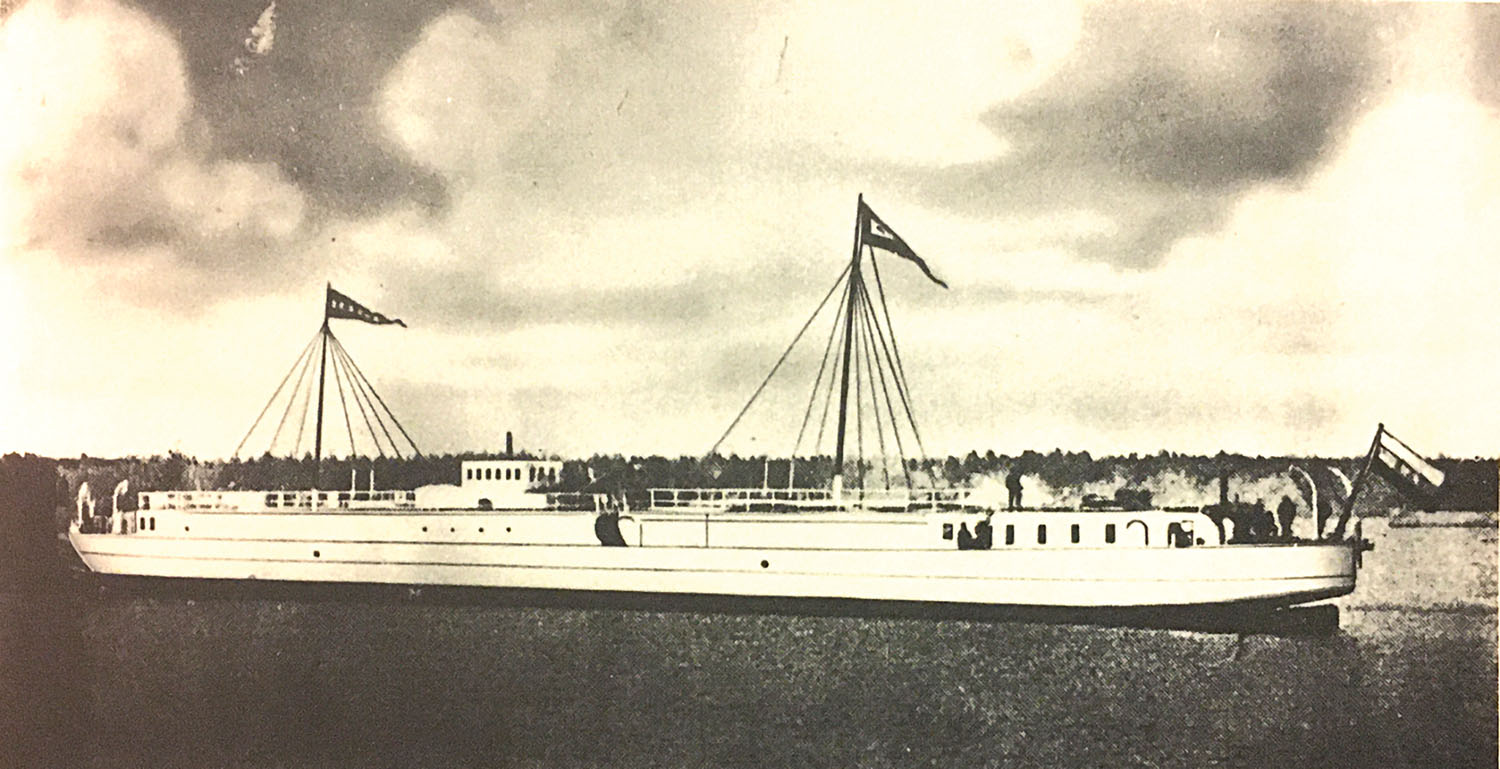

At about the same time in 1903, Swedish and Russian engineers produced a larger and more advanced barge.

The Nobel company had been looking at the new diesel technology as a way to overcome two problems in its oil transportation network. Russian steam locomotives and boats were burning heavy residual oils, and very inefficiently. This included sidewheel barges and tugs on the Volga River. Also, oil as cargo had to be transferred to rail cars at the northern end of the Volga waterway. The company wanted to use a new and larger river-canal-lake system, but there were as yet no practical, propeller-driven tankers of adequate size and power.

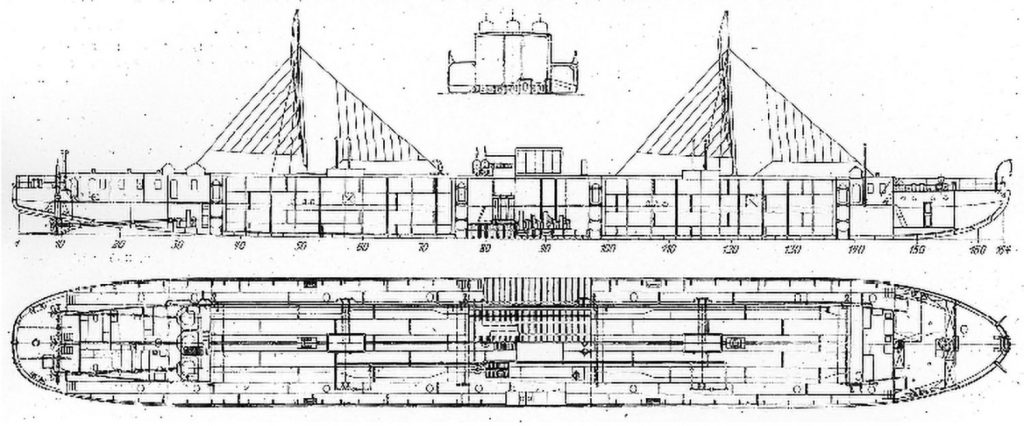

The solution was the Vandal, a triple-screw tanker and the world’s first diesel-electric vessel. It was 245 feet long with a beam of 32 feet and a draft of 6 feet.

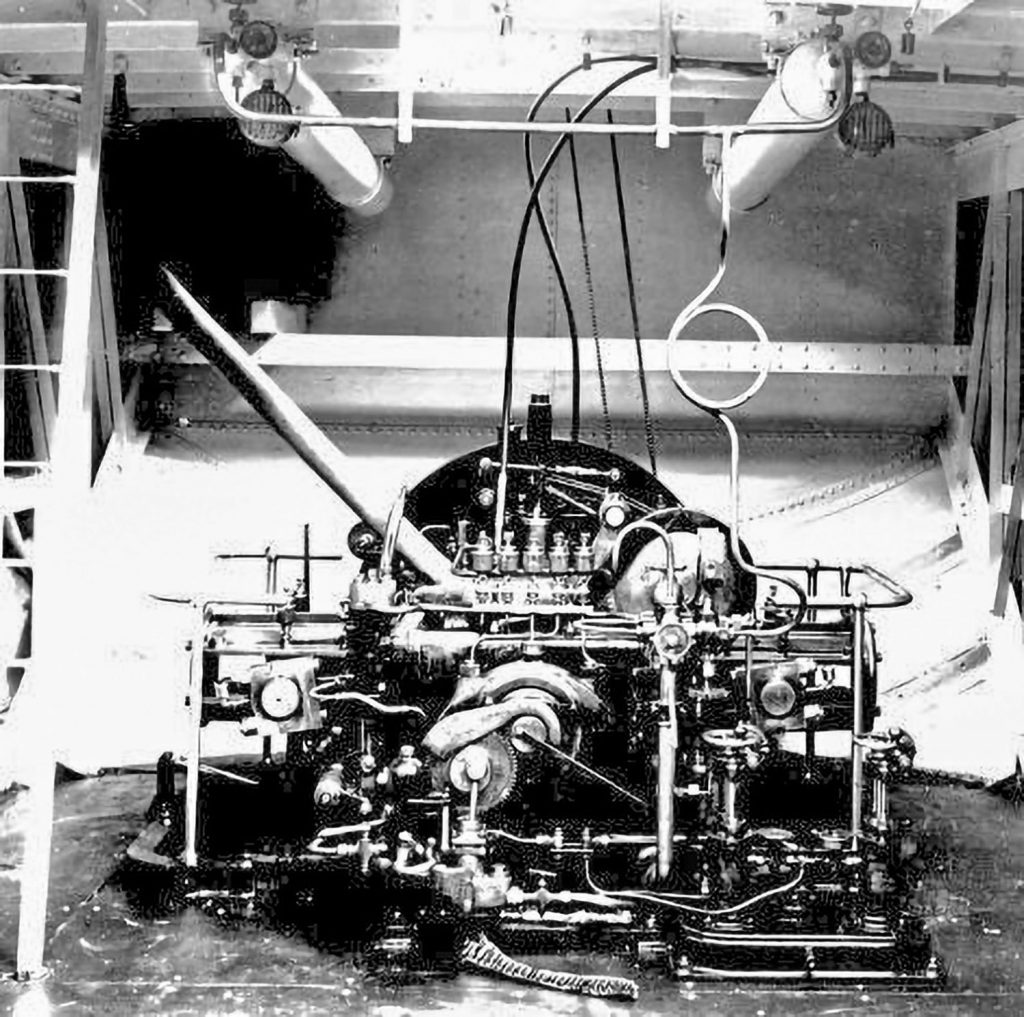

The Vandal had three diesel engines from Sickla in Sweden, each with three cylinders and developing 120 hp. at 240 rpm. The engines were midship-mounted. Each was connected to a generator, wired to a motor, and connected to a propeller shaft.

Reverse was obtained by reversing the electric motors. For each wheel, the generator, a magnetic clutch and an electric motor were all in line with the shaft. When powering ahead, the magnetic clutch was energized to couple the engine directly to the propeller. In astern, the clutch was disengaged, and the generator drove the motor in the opposite direction.

ASEA of Sweden designed and built the electrical components by adapting controls from those then in use on electric street cars.

The Vandal started service in the spring of 1903. The cargo capacity was 820 metric tons.

It’s not clear how long the Petit Pierre with its unique one-cylinder, two-piston diesel engine stayed in service on the French and Belgian canals. The Vandal, though, operated for 10 years on the 2,000-mile route between the Caspian Sea and St. Petersburg.

In fact, the Vandal was so successful that the Nobel company ordered another diesel-powered barge, the Ssarmat. It was the same size as the Vandal, but was powered by two larger diesels, four-cylinder engines adapted from a stationary model. Each engine developed 180 bhp. at 260 rpm. Unlike in the Vandal, the engines were placed near the stern and turned propellers via a semi-electric drive, which proved to be more efficient than the Vandal all-electric one. The Ssarmat also had a single-cylinder 10 hp. auxiliary diesel. The Ssarmat ran with its original engines from 1904 to 1923.

Caption for top photo: Nobel Petroleum Company’s diesel-electric inland tanker Vandal underway.