Whether it’s the river system or the Great Lakes, navigation is all about connection, said Joe Savage, programs director for the Corps of Engineer’s Great Lakes and Ohio River Division.

“Most people who are familiar with navigation know it’s all about connection,” he said. “An outage in one location affects everything up and downstream of that.”

What those in the river industry may not know is that the vast majority of commerce on the Great Lakes system is inter-lake, he said, quoting a statistic that 95 percent of U.S. shipping traffic on the lakes is internal to the Great Lakes and not foreign.

What that means, he said, is that while overseas ports are often in competition with each other, “On the Great Lakes, they see themselves as complementary. Commodities are going from one port to another, so they have a great interest in each other’s capacity, operations and maintenance.”

This is much like the river system, where cargo must also move smoothly from one location to another down the same waterway, using the same infrastructure.

The Great Lakes and Ohio River Division encompasses 355,300 square miles, including all or portions of 17 states. The division is responsible for maintaining the navigability of the Ohio River and its seven navigable tributaries as well as protecting the American shorelines of the five Great Lakes. Seven districts are within the division. They are: Buffalo (N.Y.), Chicago (Ill.), Detroit (Mich.), Huntington (W.Va.), Louisville (Ky.), Nashville (Tenn.) and Pittsburgh (Pa.).

In administrating the systems, both have a federal funding mechanism through a trust fund account, but they operate in different ways, Savage said.

While the Inland Waterways Trust Fund has a cost-share program for major construction and rehabilitation, the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund—which includes the ports, harbors and locks on the Great Lakes, among others—includes a cost-share program for all operations and maintenance, Savage said.

Both systems also have locks. The St. Lawrence Seaway system is a system of locks, canals and channels that permits vessels to travel from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes as far inland as Duluth, Minn., at the western end of Lake Superior, bypassing several rapids and dams. The five short canals (South Shore, Beauharnois, Wiley-Dondero, Iroquois and Welland) include 15 different locks.

According to the website of the St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation (SLSMC), the corporation that administers the Canadian side of the system, together the locks make up the world’s most spectacular lift system. Ships measuring up to 740 feet long and 78 feet in the beam are routinely raised as high as a 60-story building. The ships are twice as long and half as wide as a football field and carry cargoes the equivalent of 25,000 metric tons.

The largest of these is the Soo Locks, operated by the Corps’ Detroit district.

The Soo Locks

The Soo Locks are a set of parallel locks that enable ships to travel between Lake Superior and Lake Huron, the first of the four lower Great Lakes. They are located on the St. Marys River. Two of the major locks at the site, the 800-foot MacArthur Lock and the 1,200-foot Poe Lock, are operational. Two smaller locks, the Davis and Sabin, are being replaced with an additional, as yet unnamed, 1,200-foot lock as part of a multi-year project overseen by the Corps. The 253-foot Sault Ste. Marie Canal Lock, on the Canadian side, is used for recreational and tour boats.

All the locks bypass the rapids of the river, where the water falls 21 feet. The locks pass an average of 10,000 ships per year, according to the Detroit Engineer District, even though they are closed in the winter.

The number of locks on the inland river system gives the Corps of Engineers added expertise in terms of lock planning, design and construction that is not available in the lake system along because “The last one that was constructed was a generation ago,” Savage said.

So, in preparing for construction of the new Soo Lock chamber, the Great Lakes and Ohio Division is working in conjunction with the Mississippi Valley Division and the Corps of Engineers Inland Navigation Design Center, Savage said.

The Soo has some key differences with locks on the river system, however.

One is that as the U.S. shares the Great Lakes with Canada, some international vessels transit the locks.

Another difference is the weather.

“The operation of the Soo Lock is in a climate like none other that we have in the Great Lakes and Ohio Division,” Savage said. “We have a lot of cold weather issues in the upper regions of the Ohio, and I know we do in the Mississippi as well, but nothing like the Soo Lock where the navigation channels are closed due to ice during certain portions of the year.”

That makes the nine or 10 months the lock is operational critical, Savage said. It also means that all maintenance work is done during the winter months, when the lock chambers are closed to navigation.

Although the Soo Lock already has two operational chambers for freight, it remains a single point of failure on the system, Savage said.

The inland waterway industry is used to having auxiliary chambers that are often smaller than main chambers but can be used by breaking larger tows and double locking during main chamber outages.”

“That is not the case with the Soo Lock,” Savage said. “The Great Lakes industry primarily uses ships, and I’m talking about 1,000-foot Laker ships that would not fit in the smaller lock. Eighty-eight percent of the tonnage that transits the Soo Locks is limited to the use of the Poe Lock only.”

So if the Poe chamber is out of service, traffic between Lake Superior and the other Great Lakes and into the Atlantic Ocean is blocked.

The new lock will eliminate the single point of failure.

“The Soo Locks are national critical infrastructure, and their reliability is essential to U.S. manufacturing and national security,” Detroit Engineer District Deputy Engineer Kevin McDaniels said previously. “A failure of the Poe Lock would have significant impacts to the US economy, especially the steel industry. The new lock will provide much-needed resiliency.”

New Lock Chamber

The new Soo lock chamber was originally authorized in 1986, 36 years ago. It then went through a series of changes and reauthorizations, altering the lock’s dimensions to the 1,200- by 110- by 32-feet size being built today.

The most recent authorization was in 2018. Earlier this year, the new lock at the Soo received $479.9 million in funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

However, that investment will not be enough to complete the new lock, Savage said. A new analysis is being completed that will take into consideration the updated costs of construction materials and labor.

As with lock construction projects on the river system, the new Soo lock is being constructed in phases. The first phase involved upstream channel deepening.

The upstream approach channel was dredged to accommodate the largest Great Lakes vessels. That included removal of 250,000 cubic yards of sandstone and overburden beginning in spring 2020, throughout 2021 and continuing this spring.

“Phase I is nearly completed, with approximately 3,000 cubic yards of material remaining to be removed,” Carrie D. Fox, Detroit district public affairs specialist, reported in early May. “Phase I is scheduled to be complete this summer.” The Phase I contractor is Trade West Construction Company of Nevada.

Work is underway for the second season in Phase II, which includes rehabilitation of the upstream approach walls and deepening of the federal channel in the downstream lock approach. The Phase II contractor is Kokosing–Alberici LLC, a joint venture of Kokosing Industrial of Ohio and Alberici Constructors of Missouri.

Work on the upstream approach walls began in 2021, during which the first 26 of 52 coffer cells were placed to rehabilitate the upstream approach walls. Following the seasonal winter downtime, work began again this year in mid-April, and the second phase is on schedule for completion by fall 2023. Subcontractor L.B. Foster Company is supplying approximately 5,750 tons of steel sheet piling to Kokosing-Alberici for the stabilization project.

Deepening of the downstream approach has required drilling and blasting 77,000 cubic yards of material, mostly sandstone, which was then excavated and loaded into barges that moved the material above the locks. It was then unloaded and hauled to the designated disposal area.

Savage said the Corps plans to award Phase 3 of the lock construction project later this year. That is the contract of longest duration and is the largest and most complicated part of the project, he said.

Fox explained, “Coffer cells will be built to dewater the construction site, power needs to be rerouted through the facility, the Sabin Lock chamber demolished, a new chamber constructed to the dimensions of 1,200 feet by 110 feet, the Davis Lock filled in, a new pump well installed and the downstream approach walls rehabilitated.”The third phase is anticipated to take eight years to complete. That means the lock could have an early online date of 2030, Savage said.

However, he added, there are multiple factors that could require the project to deviate from the schedule, especially in a climate where the placement of concrete is not always possible because of the cold in the winter months.

Savage also notes that the Soo project is not occurring in a vacuum. The Great Lakes and Ohio River Division is overseeing eight significant navigation projects all authorized for construction. The others are the Lower Mon at Charleroi Lock, the Kentucky Lock Addition Project, Chickamauga Lock Replacement Project and the three locks that make up the Upper Ohio Navigation Project.

“So that’s eight significant locks projects in the Great Lakes and Ohio River Division where we are either under construction in planning and design prior to construction,” Savage said. In addition, he said, the division is overseeing a major rehabilitation at T.J. O’Brien Lock and Dam in Chicago, Ill.

Savage said that throughout these projects, it will be important to take advantage of the knowledge and experience of people throughout the Corps of Engineers to take advantage of synergies and build faster, better and more economical projects for the good of the country, its waterways and its people.

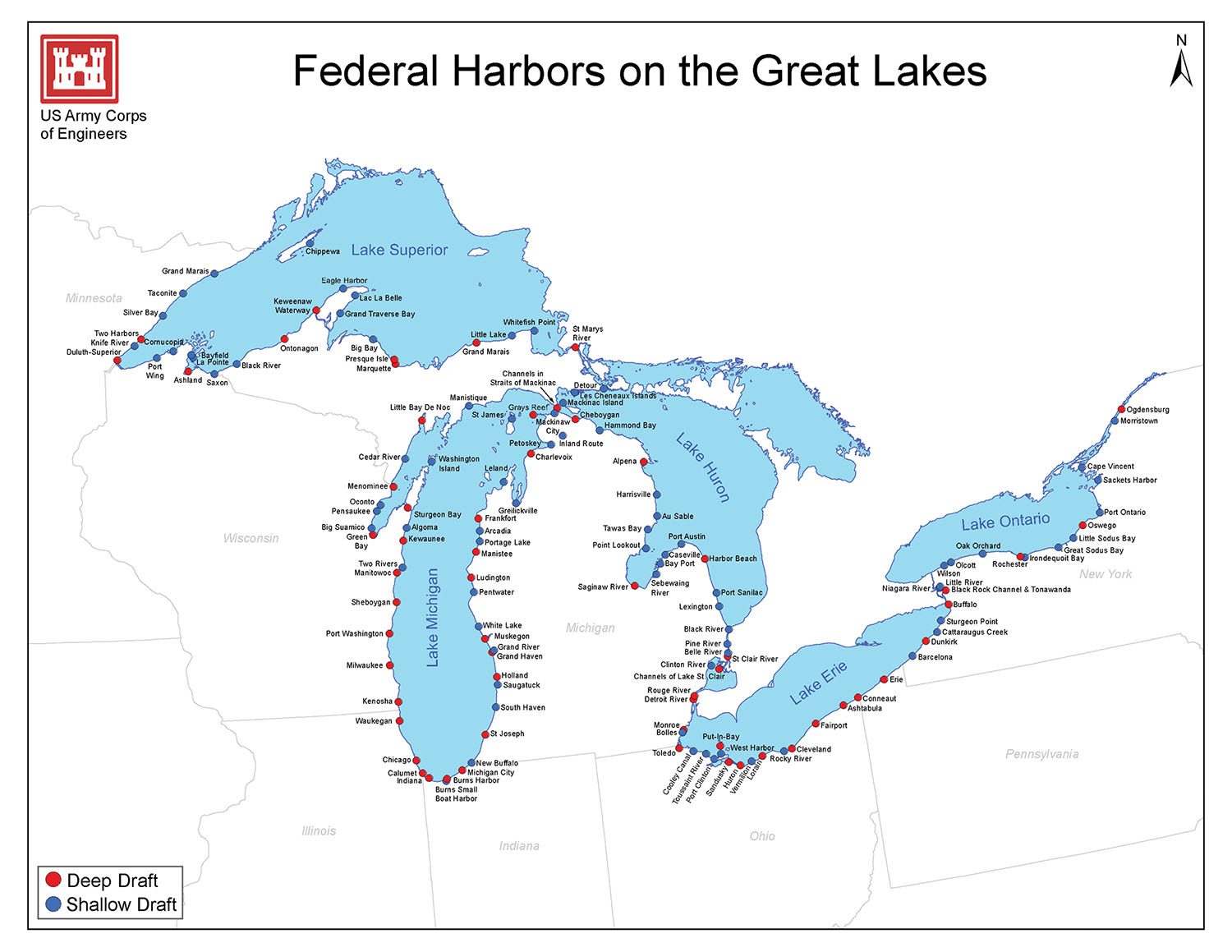

Caption for top photo: Corps of Engineers map of Great Lakes harbors.