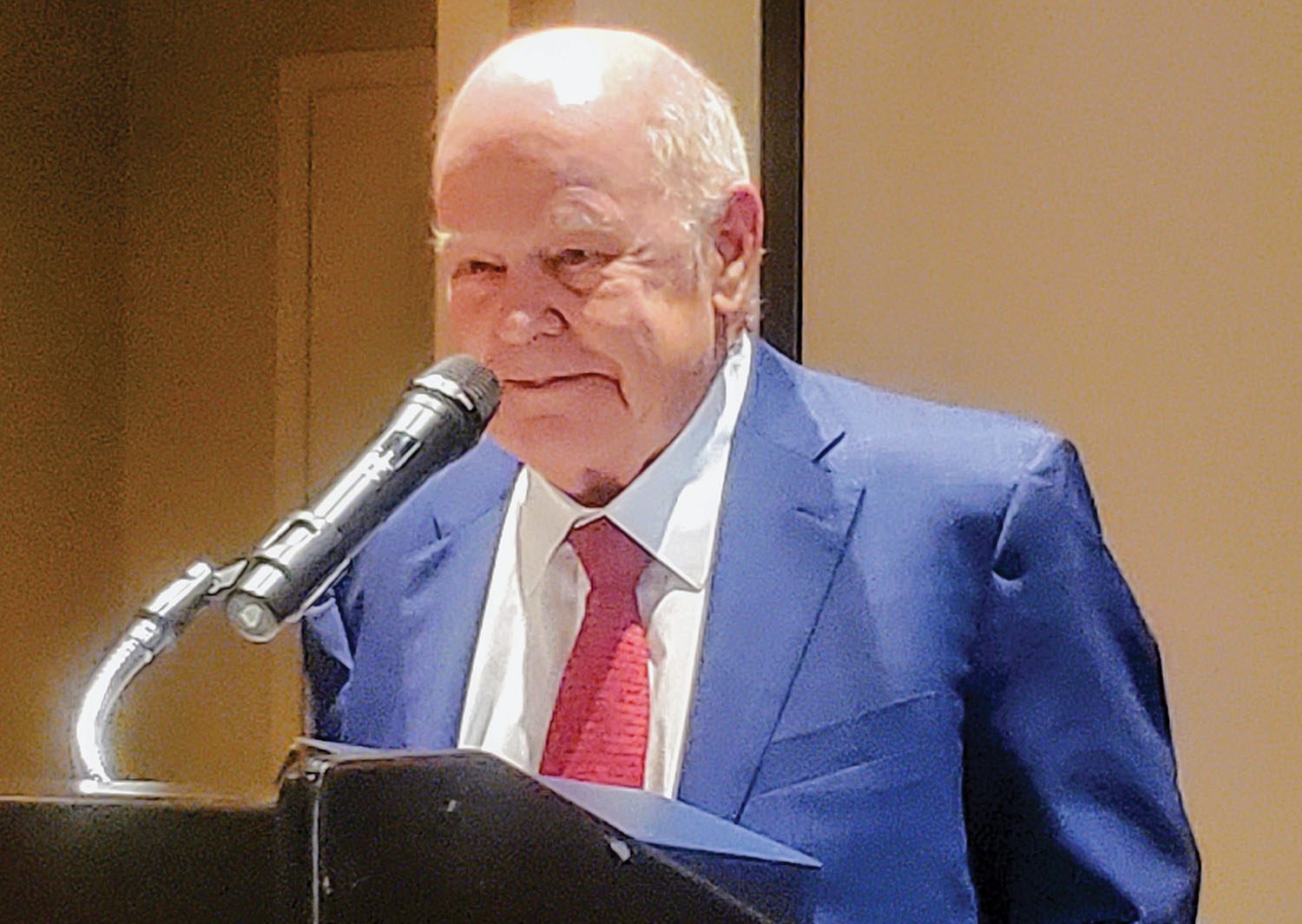

Walter E. Blessey Jr. was honored October 8 as the 2022 Maritime Person of the Year at the 88th Annual Gala of the New Orleans Propeller Club at the Metairie Country Club.

Blessey is founder and owner of Blessey Marine Services of Harahan, La. The company employs more than 750 people and owns and operates one of the youngest and largest multi-faceted inland tank barge and towing fleets in the United States, with 85 towboats and 175 tank barges. An affiliated company, WEB Fleeting LLC, operates a fleeting operation located on the San Jacinto River Basin in Channelview, Texas.

It was not the first time Blessey was recognized for his maritime entrepreneurial expertise. He served on the board of directors of The American Waterways Operators and has been a member of the executive committee, including serving as past chairman of AWO’s Inland Liquid Sector.

In 1999, Blessey was inducted into the Louisiana Business Hall of Fame, and in 2013 he was awarded Ernst & Young’s Entrepreneur of the Year for the Gulf States.

More recently, in 2019, he was awarded the Coast Guard Meritorious Public Service Award “to honor his contributions to the inland marine transportation industry, navigation safety, environmental stewardship and homeland security during his decades-long involvement with The American Waterways Operators.”

New Orleans CityBusiness awarded Blessey the 2019 Icon Award and chose him as an honoree for the 2020 Driving Forces.

Tulane University bestowed upon him the Life Time Achievement Award for the class of 1967. He holds degrees in engineering and law from the New Orleans-based university, and he was elected Tulane student body president while in law school. In addition to participating in numerous non-profit activities, he served on the board of directors for Junior Achievement and is now a director emeritus.

But he cites his marriage to Jane Ann Blessey as one of his greatest awards. It happened that the award banquet fell on her birthday, and the Propeller Club’s executive director, Cathy Vienne, was quick to present her a bouquet of flowers as Blessey mentioned it.

Respect For His Crews

Every Christmas, Blessey calls each of his boats to thank the crews for their hard work. Some calls last only five minutes. Others take 40 minutes. It takes him three days to call all his vessels.

And, by the way, don’t call him “Mr. Blessey.” “Mr. Blessey was my dad. Call me Walter,” he is known to say, even to a newly hired deckhand.

During his remarks, that respect for his employees became apparent, as he told of being treated poorly in his former job at what was then Middle South Utilities, a multi-state power generating and distribution utility, now known as Entergy. It would leave a lasting impression, and lessons learned would have an important influence in his life.

“I do not know what they hired me for,” he explained. “I picked up one VP’s car after it was being serviced. The chairman did ask me to write an opinion on a tax issue. I really had nothing to do.”

Being treated poorly and with few duties, Blessey said he was miserable at the job. Company vice presidents seemed oblivious to employees below them, but his father told him not to give up that job until he had another one lined up.

At the time, the federal government made it illegal to burn natural gas in boilers. Middle South had to buy oil to fuel the power generation stations, but no one in the company knew much about buying or transporting it.

The utility interviewed two executives from the oil business to hire as company oil buyer, Blessey remembers. Each wanted a salary of $60,000 per year. Balking at the cost, Middle South Utilities formed a new three-person company, System Fuels, with a president, his secretary and Blessey.

The president had been with LP&L for 40 years and was paid $38,000 a year but knew nothing about oil and barging, Blessey explained, adding, but “he sure loved lunches and dinners with the vendors paying for it.”

So Blessey dove headlong into learning both the buying of fuel and transporting it. He said Ed O’Donnel at Chotin Transportation taught him about transporting fuels, and an Exxon executive helped him learn the fuel-buying side.

Within six months of System Fuels’ formation, the federal government installed price controls on fuel at 30 cents per gallon. Oil companies did not want to sell at that price. So, he had to shop outside the U.S. to find available fuel for the utility.

Blessey said he found #2 oil available in Rotterdam, with the price at the tank of $1 per gallon. About the same time he learned the Koch oil company had oil they did not want to sell at the government’s controlled price.

“So I proposed a swap with them, giving us 35 cents a gallon for 42 million gallons,” Blessey said. Initially Koch refused, but after reconsidering, they did the deal. Koch would also make 35 cents a gallon on the deal.

The oil was at the Koch refinery in the north, so Blessey swapped it to Union 76 in Port Arthur for five cents per gallon. He checked with his legal department to verify the transaction was legal, and it was.

“So, System Fuels was paid nearly $15 million, and the oil was in Port Arthur,” Blessey said of his innovative maneuvers. “I got no credit for doing this on my own. I got a raise to $12,800 at the end of the year,” a raise of only $800. But he got no “attaboy” from higher-ups in the company.

System Fuels had recently signed a contract with International Tank Terminal, and Blessey put a bug in their ear that, with all their tank capacity, they should form a trading company.

“They asked me to start one,” he continued. “I gave them a written proposal where I was taking 11 percent of what I made. They accepted.”

So, for the next four years, his 11 percent made him “hundreds of thousands of dollars” each year. But in year four, the company tried to walk around him, pumping oil into another tank to lower his earnings, which Blessey discovered.

Then in June of year five, the company asked Blessey to work for free for the six remaining months of the year and then pay him a straight salary of $60,000 per year with no commissions.

“They made nine times what I made,” he said. “I left, and they closed the trading company door shortly thereafter. Talk about cutting off your nose to spite your face.” He then formed his own trading company.

“Bill McNeil was our consultant,” Blessey said. “He was awesome.”

By then, he knew both the petroleum business and transportation business.

It allowed him to go out on his own, traveling Europe and Africa, buying and trading oil for 10 years.

“How did this happen?” he asked rhetorically. He got no attaboys, but lessons learned would follow him. He would use them building his maritime business.

And now he has 85 boats and 175 barges.

“I learned how to treat people at my company with respect,” he said.

Caption for photo: Walter Blessey Jr. accepts the Maritime Person of the Year award from the New Orleans Propeller Club. (Photo by Richard Eberhardt)