The Gulf Coast chapter of the Western Dredging Association (WEDA) held its annual meeting in New Orleans November 7–9. Donald Hayes, also known as “the dredging professor,” presented his Dredging 101 short course at the start of the three-day meeting, with representatives from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the state of Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority holding a morning-long “speed dating” session with industry personnel November 9. Sandwiched in between was a content-rich day of presentations that ranged from a big-picture look at the history of flood control in the Mississippi River Valley to snapshots of dredging activities in the Galveston, New Orleans and Mobile engineer districts—and a lot in between.

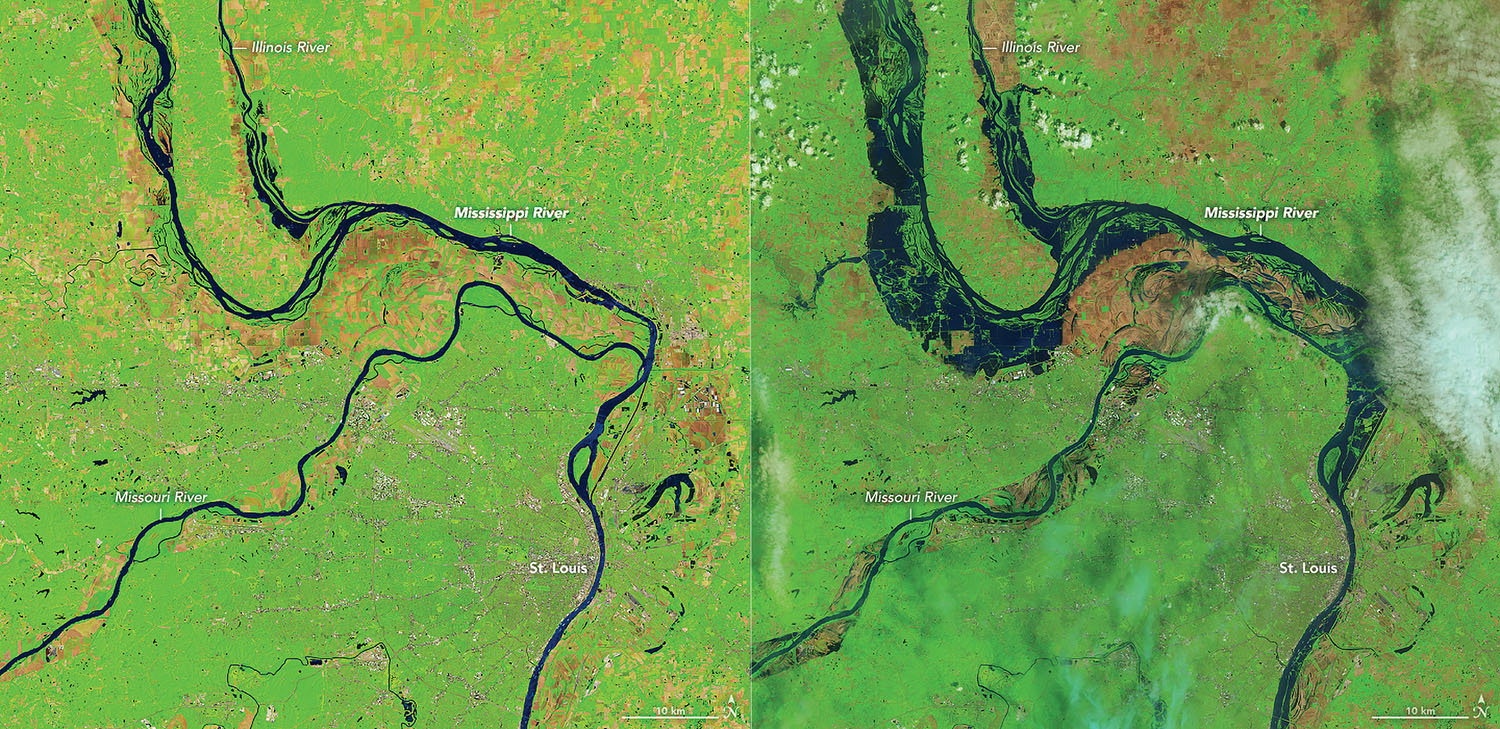

Norma Jean Mattei, chair of the University of New Orleans Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering and a member of the Mississippi River Commission, jump-started day two of the chapter meeting with a look at the evolution of flood control and navigation on the Mississippi River.

In beginning her survey of flood control efforts on the Mississippi River, Mattei explained why the region is important—namely that it’s the longest navigable river system in the world and that it meanders through the most fertile farmland in the world. But there’s one big problem.

“The Mississippi River does not want to stay where it is now, and it didn’t start its life where it is now,” Mattei said. “And we are really working hard to keep it where it is, because we do rely on it.”

Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, communities along the river and the federal government began building levees along the river, doing revetment along its banks and implementing cutoff programs to help speed up the river and allow it to self-scour its channel.

Then came the Great Flood of 1927, which in today’s dollars caused about $1 trillion in damages and losses. The cost in 1927 dollars was about $1 billion, Mattei said, which was a third of the federal budget that year.

“That’s when the Congress said, ‘This is way too big of a problem for us to ignore. We’ve got to figure this out,’ because it resulted in a huge loss of life, a huge migration of people out of the Delta areas and lots of loss of properties,” said Mattei, who later added, “It’s still usually noted as the greatest disaster in the history of the United States.”

The Great Flood gave birth to the “Jadwin Plan,” which eventually became the Mississippi River & Tributaries Project (MR&T). At the center of the MR&T is the “project design flood” and the flood control features built to pass such a flood. Mattei described how the Corps of Engineers would go on to build a series of floodways and spillways: Birds Point-New Madrid in Missouri; Boeuf Floodway in Arkansas; Morganza north of Baton Rouge, La.; and Bonnet Carré just above New Orleans. In addition, the Corps built federally maintained levees on either bank of the lower river, and backwater channels were identified for accepting water from the Mississippi during floods. By the mid-20th century, the Corps had built the Old River Control Complex to keep the river from changing course to the Atchafalaya.

All that investment in flood control had a dual benefit, Mattei said, in growing commercial trade and transport on the river, such that, by 2021, agricultural exports amounted to $177 billion. Mattei noted some maritime infrastructure successes of late, like the deepening of the Mississippi River Ship Channel to 50 feet, which actually broadened the “ribbon of farmland” where waterborne transport is more economical than by road or rail.

At the same time, though, most of the locks on the system measure 600 feet by 110 feet, which is restrictive in relation to modern tow sizes. Other challenges Mattei mentioned were the frequency of flooding, the changing nature of floods and the juxtaposition of extreme low-water events, which also hampers navigation. Mattei closed her presentation by overviewing the historic amount of funding for waterway projects anticipated from the fiscal year 2022 budget, the Hurricane Ida supplemental and the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act.

“This is a generational investment, and it’s an investment across the board in a lot of our critical infrastructure, including our inland waterways,” she said.

As the day progressed, representatives from across the Gulf Coast region discussed ways federal, state and local funding is translating into waterway improvements. Over lunch, Sean Duffy, executive director of the Big River Coalition, discussed the Mississippi River Ship Channel deepening project. Just prior to that, WEDA Gulf Coast attendees heard updates on both the Houston Ship Channel’s current expansion, called Project 11, and dredging operations within the Mobile Engineer District.

Attendees looking for technical sessions had plenty to choose from, with a trio of technology-focused sessions following the lunch. In addition, later in the afternoon, Kelsey Lank, a production engineer with Great Lakes Dredge & Dock, discussed her findings with regard to a wide range of strategies for protecting turtles from dredge drag arms. Types of turtle mitigation strategies included physical, audible and visual devices, with a remote-controlled shark drone receiving the most intrigue and interest from the crowd.

The day’s presentations concluded with a close look at dredging in Baptiste Collette Bayou and the beneficial use of dredge material to build up bird islands, including Gunn Island, which was the site of an estimated 50,000 nesting birds in 2020.

The WEDA Gulf Coast Chapter rotates its annual meeting between Mobile, Ala., New Orleans and Galveston, Texas. Past presentations, as well as the slides from the November 9 industry-agency collaboration day, are available online at www.westerndredging.com under the “regional chapters” tab.

Caption for graphic: From Norma Jean Mattei’s presentation at the WEDA Gulf Coast chapter meeting: two satellite views of the Mississippi, Missouri and Illinois rivers, one from June 5, 2018 (low water, left), and the other from May 7, 2019 (high water, right).