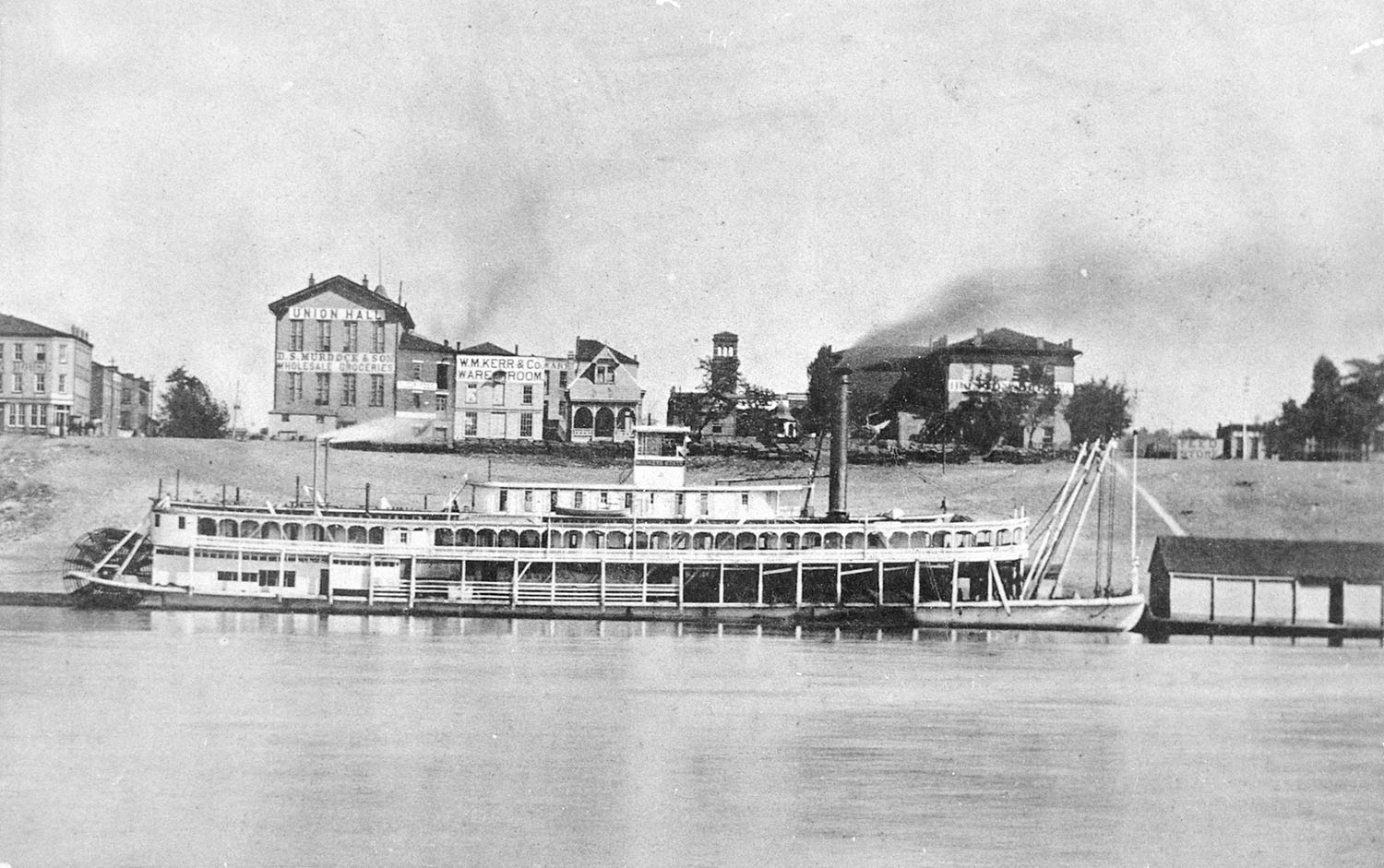

There were two sternwheel packets named Granite State. According to Way’s Packet Directory, the first was built at California, Pa., in 1870 for Capt. Wash Kerr, who used it in the Pittsburgh–Portsmouth, Ohio, trade throughout most of the time until it was retired in 1878. A new Granite State was built at Cincinnati in 1879 with a wood hull 221 by 35 and utilizing the Rees engines from the first boat. These engines were 16’s with a 5.5-foot stroke. The stern paddlewheel was 22 feet in diameter and had buckets 26 feet long. This boat was also owned by Kerr and was in the Pittsburgh–Portsmouth trade.

Kerr died in 1880, and after this Capt. Wash Honshell of Catlettsburg, Ky., and T.T. Johnson owned shares in the boat. On November 1, 1882, the second Granite State would become involved in what would be known as “The Ashland Tragedy” at Ashland, Ky. There is no mention of this event in Way’s, and Capt. Ellis C. Mace in his River Steamboats and Steamboat Men mentions the first Granite State as well as Capt. Wash Kerr and Capt. Will Kirker, who was master in 1882, but makes no reference to the “tragedy” even though he would have been 20 years old at the time and working as a watchman aboard the packets Fannie Dugan and Louise, both owned by the Bay Line of Ironton, Ohio. The events are well documented in The Ashland Tragedy, a book originally published in 1885 by James M. Huff, a witness to many of the happenings. The book was revised and republished in 2021 by researcher Herbert E. “Joe” Castle.

The Ashland Tragedy began with the murders of three young people at Ashland in the early morning hours of December 24, 1881. The young people were 17-year-old Robert Gibbons, his 14-year-old sister Fannie Gibbons and 14-year-old Emma Carico. Carico lived next door and was staying with the Gibbons youths in their home while their mother and a younger sibling had travelled across the Ohio River to Ironton for the night to visit a married daughter. About daylight, Emma Carico’s mother looked out a window of her house and saw that the Gibbons home was on fire. She raised the alarm, and it was later discovered that all three young people had been murdered and the house set on fire. Examinations indicated the girls had been molested also.

Not surprisingly, the community was both shocked and incensed over the killings. A citizens’ committee was formed of leading members of the community, and well-known investigators arrived in the efforts to find the responsible party. About 10 days after the murders, a man named George Ellis began acting suspiciously. He ultimately confessed to having been involved with the events, with the exception of the actual murders, and implicated two other men, Ellis Craft and William Neal, as having been the actual murderers. All three were arrested and, given the sentiment of the local community, were sent to Maysville, Ky., (aboard the first packet named Hudson) pending the trials.

Neal and Craft were tried in the Boyd County Court at Catlettsburg in back-to-back trials beginning on January 16, 1882, found guilty and sentenced to death. They were taken to Lexington, Ky., for safekeeping, pending appeals. George Ellis was transported with them as his trial was set for May 1882. The group was escorted by a complement of state militia. Ellis was returned for trial on May 30, tried and convicted on June 3 and sentenced to life imprisonment. That night a mob, upset that he had not been sentenced to death, took him from the county jail and lynched him from a tree within sight of the burned home where the murders had taken place.

Craft and Neal won their appeals on a technicality, and they were returned to Catlettsburg for trials in the Boyd County Circuit Court in October 1882. A change of venue was requested and approved by the judge, who set the new venue as Carter County (Grayson, Ky.) with trial dates in February 1883. The state militia was to escort the two back to Lexington to await trial. On November 1, 1882, the militia, composed of 215 soldiers in seven companies, marched with the prisoners to the Catlettsburg wharfboat. There they boarded the Granite State, which was commanded by Capt. William Kirker. A crowd of some 200 had demanded that the militia hand over the prisoners to them, but Major John R. Allen, in charge of the soldiers, refused, and there was no further trouble.

The Granite State departed Catlettsburg and headed down the Ohio River. A short time later as it came in sight of Ashland, the local ferry started out toward the packet. A small number of people were aboard the ferry, and two shots from small pistols were heard. The soldiers on the Granite State then opened fire. An estimated 1,500 rounds were fired by the soldiers, and not at the ferry, but at a large crowd of people on shore at Ashland that had gathered simply to watch the packet pass by. Several in the crowd were killed, and many were wounded. In testimony later, Capt. Kirker stated that he never heard any gunfire come from the people on shore, and that he felt neither the soldiers nor their prisoners were in danger at any time. He further stated that Major Allen had effectively commandeered his boat, and that he had no authority aboard at the time.

Kirker’s testimony was corroborated by other witnesses, such as J.C. Nelson, an American Express manager who had been aboard the Granite State, and Sherriff John J. Kouns, who was aboard with the prisoners. These two also stated that the only damage they saw to the packet was caused by the soldiers. In his report, Major Allen attempted to exonerate his troops and place blame on the unarmed crowd for simply being there. The news stories of the day seemed to portray eastern Kentucky as lawless and under mob rule. Giving a glance at the still raw wounds of the recent Civil War, Kentucky Gov. Luke P. Blackburn, a Confederate sympathizer during the war, derided the citizens of Ashland and eastern Kentucky, which had largely supported the Union, and said while he was sorry for the dead citizens, he backed the troops and would send 12 regiments, if necessary, to protect the prisoners at the February trials.

The February trials were held without incident, with verdicts of guilty and sentences of death. Both were hanged in Grayson, Ky., Craft on October 12, 1883, and Neal on March 27, 1885.

The Granite State hopefully lived a more mundane life after the events of November 1, 1882. Way’s shows the boat as being owned by the Memphis & Cincinnati Packet Company in 1888 under Capt. Don Marr. It sank in the Grand Chain on the lower Ohio River near Mound City, Ill. (with no date given), and was lost. The hull was recovered and served for many years as a wharfboat at Catlettsburg until 1913. Had these events transpired some five years later, perhaps they would have been chronicled in a fledgling Waterways Journal.

Caption for photo: The Granite State new at Ironton, Ohio. (Thornton Barrette photo, David Smith collection)