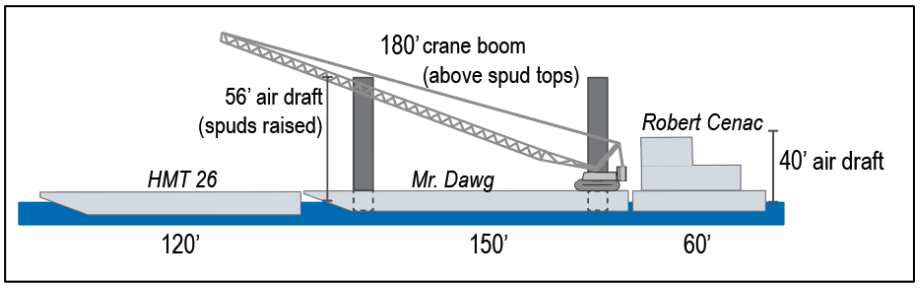

The mv. Robert Cenac, a 60-foot-long, 1,400 hp. towing vessel in Al Cenac Towing’s fleet, was pushing a 150-foot-long crane barge called the Mr. Dawg eastbound on the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW) in the early-morning hours of March 6, 2022, when the head of the crane boom hit the outermost stringer of the Houma Twin Span Bridge, causing $1.5 million to $2 million in damage and impacting vehicular traffic over the busy bridge for 10 days.

According to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), an employee with Sealevel Construction, which owned the Mr. Dawg, contacted an Al Cenac Towing sales representative around 8 p.m. on March 5 to charter a vessel to transport the Mr. Dawg and another deck barge from the Houma area to the Louisiana Offshore Oil Platform (LOOP) facility in Clovelly, La. During that phone call, the Sealevel employee reportedly told the Al Cenac Towing representative that the crane boom had been lowered “below the top of the fully raised barge spuds,” which were said to be 50 feet high, according to the NTSB report.

“NTSB could not confirm if this information was passed to the Robert Cenac’s captain,” stated the NTSB report, which was released March 23.

By about 10 p.m., the crew aboard the Robert Cenac began building tow, with the captain noting that “the crane boom was about 10 feet higher than the spuds. … He therefore estimated the boom head was ‘roughly 60 feet’ above the water. He also understood all of the bridges on the passage had 72 feet of vertical clearance,” according to the report.

Around 11:30 p.m., a representative from Al Cenac Towing sent a text to a marine logistics coordinator at Sealevel to say, “Hey, could you find out the height of the boom on the crane? They [the crew of the Robert Cenac] just want to confirm it. It’s a little taller than the spuds.” A series of texts between the two companies and internally between Sealevel personnel ensued, but “no confirmation was sent to Al Cenac Towing nor the towboat,” the NTSB said. The captain ultimately decided he was comfortable with the height of the crane boom, and the tow got underway.

The mate arrived in the wheelhouse at about 11:40 p.m. for watch change. The Robert Cenac was about a mile from the Houma Twin Span Bridge. At 12:38 a.m. on March 6, the head of the crane boom hit the bridge with a forward speed of 4.3 mph. The captain, who returned to the wheelhouse, reported the incident to the Houma Police Department, Al Cenac Towing and the U.S. Coast Guard. The captain also called Sealevel, which sent a crane operator to the vessel shortly after 9 a.m. The crane operator, who reported that the boom was between 26 degrees and 30 degrees, lowered the crane to about 15 degrees. At the captain’s request, he lowered it further to 5 degrees.

The tow got back underway at 12:30 p.m., only to turn around due to shallow water in Bayou St. Denis.

The bridge was closed to vehicular traffic until 11 a.m. March 6, at which time one lane reopened. The second late opened March 16.

Upon closer investigation, the NTSB found that a series of incorrect estimates had been made regarding the air draft of the Mr. Dawg and the Houma Twin Span Bridge. The bridge actually had a vertical clearance of 72.8 feet according to charts, which meant that “the captain’s estimate of 60 feet [for the crane boom] was at least 12 feet short,” NTSB stated. In addition, the Mr. Dawg’s spuds were actually about 56 feet. Had the captain known that, his estimate of the boom being 10 feet above the spuds would put the tow’s air draft at 66 feet. “This would have created a narrower margin of safety, which may have caused the captain to reconsider getting underway until the tow’s actual air draft was known,” the NTSB report stated.

Ultimately, the NTSB concluded that the probable cause for the incident was “the tow captain’s incorrect estimate of the crane boom height and his decision to depart before getting a confirmed height from the crane barge owner.” Lack of information from the crane barge owner contributed to the incident, the NTSB said.

The NTSB recommended that operators ensure they have “accurate and objective data before getting underway.” Voyage plans should assess operational risks and hazards, the NTSB said, which include air draft concerns and vertical clearances of bridges along a vessel’s route.

Caption for top graphic: Tow arrangement of Robert Cenac and barges at time of accident. Scale approximate. (NTSB graphic)