Climate Variability Threatens Viability Of Mississippi River Ship Channel

By Sean Duffy

The Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon (BMP), sometimes referred to as the “frequency illusion,” describes a tendency where, once a person learns about a specific subject, he or she is increasingly likely to notice it. I remember thinking about this phenomenon after a Loyola class session for the Master Naturalist program. I learned how to tell the difference between monarch butterflies and the lookalike Gulf fritillary, then came home to notice I had both types of butterflies in my back yard.

After the tragic allision of the mv. Dali with the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore, Md., I saw BMP on display in maritime commerce and the media. People were talking about and focused on bridge safety, especially for bridges that span commercial navigation channels. In my area, the bridge collapse in Baltimore has made people wonder about local bridges and the size of ships calling on the Mississippi River. There are seven bridges that cross over the Mississippi River Ship Channel from the Baton Rouge I-10 bridge to the Crescent City Connection (CCC) in New Orleans.

All of this came up during my recent interview with a local talk radio host, Newell Normand of WWL Radio. Reflecting on the tragic allision of the Dali and the Key bridge, which resulted in six deaths, his comment was about “things that must keep you up at night.”

What keeps me up at night? A bridge allision, for one. But there’s more: a vessel grounding at the Pilottown Anchorage and the long-term closure of the Big River to vessel traffic that would result, like the 21-day closure in 1989. Or a vessel collision due to Federal Aids to Navigation not being operational. Or the loss of flow in the river threatening the Mississippi River Ship Channel. Or any allision or collision that could be avoided with access to critical sensors, like air gap sensors and current meters that could be synced to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Lower Mississippi River PORTS program. Or the crevasses between Belle Chasse and Head of Passes and their impact on navigation and our freshwater drinking supply.

Since the downing of the Francis Scott Key Bridge, I’ve heard people claim we do not have ships as big as the Dali on the Mississippi River. That’s simply inaccurate. There are ships longer, wider, heavier and deeper than the Dali calling on the Mississippi River. Below the Crescent City Connection (CCC) in New Orleans, the ship channel is only limited by the depth of vessels with a maximum freshwater draft of 50 feet.

Now, if your definition of big is related to height, you may still be wrong, because the cruise ships that call the Port of New Orleans also have very high vertical clearances (air gaps). That’s the main reason the Erato and Julia Street Cruise Terminals are below the CCC and one of the factors that led the Port of New Orleans to focus on St. Bernard Parish for the location of the Louisiana International Terminal, approximately a dozen miles downriver from the CCC.

What else keeps me up at night? I am gravely concerned about how dramatic hydrological changes, driven by climate variability and relative sea-level rise, will impact safe navigation on the Mississippi River Ship Channel from Baton Rouge to the Gulf of Mexico.

It’s like the song titled “New Orleans is Sinking” by the Canadian band The Tragically Hip. One line has been stuck in my head the last few years during historic droughts:

“My memory is muddy, what’s this river that I’m in?

New Orleans is sinking, man, and I don’t wanna swim.”

It’s a wonderful song and prophetically accurate to a degree. Not only is New Orleans sinking, but it’s also drowning and being invaded by the Gulf of Mexico through hydrologic pressures related to crevasses becoming larger during periods of high river and then flowing inward during low-water events. Too much or too little water—both are sweet spots for danger. The crevasses introduce salt water from the Gulf into the Mighty Mississippi during extreme low water, like we’ve seen the past two years.

During the extended drought, which is forecast to continue for a third year, saltwater drifts upriver against the reduced flow of the Mississippi, which drains 41 percent of the contiguous United States. The flow of water through the Mississippi is dependent on heavy rain or icy precipitation like snow and ice. Without heavy precipitation, the riverine system is heavily impacted by the advancing influences of the Gulf of Mexico.

Forecasting Challenges

I recently had a discussion with leaders from NOAA, including a regional director on climate science, about some challenges related to long-range weather forecasting. The main reason for this discussion was the prediction in 2019 that noted climate forecasts were concerned about increased precipitation and the likelihood of more high-river periods. The Great Flood of 2019 saw the largest volume of water ever pass down the Mississippi River, passing significantly greater amounts than other historic floods, including 1927 and 1973. In 2019, the Bonnet Carré Spillway upriver from New Orleans was opened for the first time ever in back-to-back years. In fact, it was operated twice in 2019, also a first. Prior to that period, Bonnet Carré was operated about once a decade.

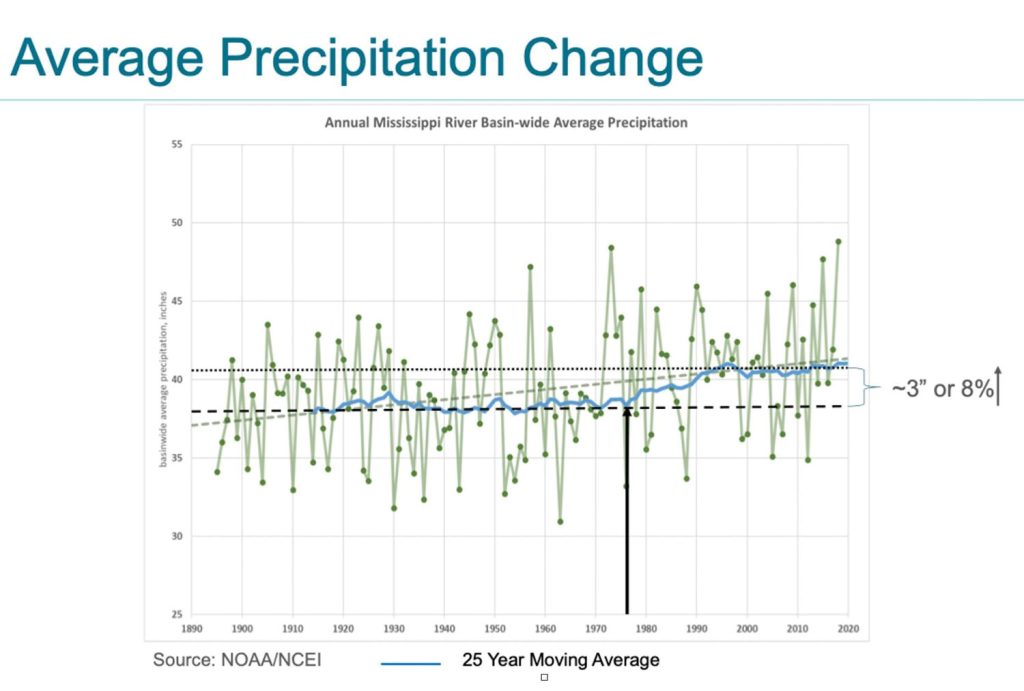

Since 2020, though, we have not had much of a high river and have now seen three ongoing consecutive years of extended drought. The accompanying graph on average precipitation change was used by a NOAA representative for a presentation in 2019.

My question is this: Is it time to adjust this graph, or will the three years of drought be followed by multiple years of record precipitation? Or can we really predict long-term precipitation trends, especially as climate variability is factored in? It seems to be warmer everywhere in the United States, but major extreme weather events seem to have become so common that we now have buzzword catch phrases like “Atmospheric River” and “Bomb Cyclone.”

For the past two years, due to drought and low flows in the Mississippi River, saltwater encroachment has led the Corps of Engineers to construct a saltwater sill below Belle Chasse near Mile 64. Prior to that, the last time this was required was in 2012, right on the same 10-year average as Bonnet Carré. Will it be necessary in 2024? This would not surprise me.

Over the last few years, I have been getting questions from longtime river pilots, discussing things they had never seen before. In searching for answers, I formed a working relationship with several scientists from Tulane University’s River-Coastal Science & Engineering Department. I was studying some river flow measurements provided by one of their colleagues to better understand why we needed to dredge in Southwest Pass with a reading of 3.5 feet on the Carrollton Gage (New Orleans), with the forecast indicating the river stage would continue to fall. Historically, dredging in Southwest Pass was needed when the Carrollton Gage was at 10 feet or higher and projected to rise.

Working with the scientists at Tulane and with data from the Corps, we found that on a day when the flow at Belle Chasse was at 776,000 cubic feet per second (cfs.), with a corresponding reading at the Carrollton Gage of 12.1 feet, the flow at Southwest Pass was just 226,000 cfs.

Then it struck me. This loss of flow wasn’t only due to the formation or growth of crevasses. It was also due to South Pass, the original outlet that was deepened by Capt. James Buchanan Eads, which had just been dredged for the first time in 14 years. Increased flow through that channel was pulling water away from Southwest Pass. On May 24, 2022, that was the equivalent of 61,378 cfs. of water.

I have since compared the Mississippi River to a garden hose with a bunch of holes in it, with most of the large ones on the eastern side. The east bank is ground zero, since below Bohemia (Mile 46 Above Head of Passes) there are no levees. The largest of the crevasses on the eastern side is Neptune Pass, which grew during the 2019 flood and on May 24, 2022, had a flow of over 118,000 cfs. This caused shoaling in the channel and for the first time ever required dredging at Mile 22 Above Head of Passes. Until five years ago, we had never dredged above Mile 11 Above Head of Passes. This has now become more commonplace due to flow loss.

In the flood of 2019, Neptune Pass was capturing more than 30 percent of the river’s flow.

Both Directions

The thing about hydraulics is that these crevasses function like straws, and the water can and does flow in both directions. During high or medium flows in the river, water moves outward, causing the crevasses to grow. During low water, flow reverses and introduces seawater to the river.

Through the work with the Tulane river scientists, I was asked to co-author a journal article that detailed a lot of this information and raised the level of concern. Can we develop resilient ports? As deltas drown in relative sea-level rise, can we adapt our waterways to be resilient?

The study, by Dr. Mead Allison, Dr. Ehab Mesehle, Dr. Barbara Kleiss and Sean M. Duffy Sr. (the Mississippi River Navigation Guy), is titled “Impact of Water Loss on Sustainability of the Mississippi River Channel in its Deltaic Reach.” The following is a quote from the abstract:

“Together these results indicate that (1) river containment and the sustainability of the navigation channel is threatened, (2) sediment load reaching the seaward end of the delta may be insufficient to avoid major degradation and (3) the increased freshwater flux into adjacent shallow coastal water bodies has unknown implications for coastal hypoxia and food webs, including commercial species (e.g., oysters) and marine mammals. Future acceleration in sea level rise rates and tropical storm frequency/intensity likely will worsen these trends.”

This study is available online here.

This may not be my only published scientific study, as the band is getting back together to delve into some of the impacts of changes to the sediment load.

The fact is, climate variability is here. The National Weather Service’s Lower Mississippi River Forecast Center has confirmed that, due to the influence of the Gulf of Mexico, the Carrollton Gage no longer accurately reflects river stage measurements during low-water periods. Furthermore, discharge flow at Red River Landing is also compromised due to the Gulf advancing upriver. The lowest reading on the Carrollton Gage in modern history happened during the extended drought of 1988, with a reading of 0.1 feet. The lowest reading during the extended low water of 2023 was 1.1 feet (November 29, 2023, at 1400 hours). I almost fell out my chair when I saw the gage. I called both the Corps and National Weather Service, who confirmed the gage was operating properly. That was the lowest reading in a decade.

During low water, the Carrollton Gage is also now influenced by tidal variance and wind direction, changes that have never been seen before.

The truth is, it’s more tragic than hip that New Orleans is sinking, drowning and that this Mighty River is being challenged now. These changes are occurring rapidly and will require holistic coordination to fill in the crevasses and preserve the stream power.

Capt. Eads knew almost 150 years ago that the way to reduce, prevent or wash away sediment was to keep the flow in the river. He harnessed the river’s own power to scour out South Pass. The main channel was later moved to Southwest Pass, but hydraulics do not change with a software update. The laws of water remain unchanged.

Eads was actually influenced by Robert E. Lee when he worked for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1837. To remove sandbars that were solidified by tree growth and blocking the flow of the river and hampering navigation, Lee built a jetty that focused the water pressure on the islands, which were washed away by the stream power.

When you are working in your yard and hosing off the sidewalk, you wash dirt away using your nozzle’s jet stream, not the shower setting.

Keeping the flow in the river is critical to our future, and a consolidated effort to do so will buy time to help better address our response to sea-level rise to protect New Orleans and the nation’s economic superhighway.

Saltwater encroachment is an active threat that will challenge our ability to provide freshwater for the city of New Orleans and below. Areas below New Orleans had salinity levels that exceeded the 250 parts per million safe threshold tenfold for approximately nine months. America’s great river, our farmland, drinking water and the ship channel, which has an economic value of approximately 7 percent of the country’s annual gross domestic product, are all at risk.

Climate change is already happening on waterways and aquifers across the country. Port and navigation industry representatives must get engaged, follow and comment on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers study known as the “Lower Mississippi River Comprehensive Management Study” and the National Academy of Sciences-funded study titled “Mississippi River Delta Transition Initiative Consortium,” or MissDelta. The navigation industry should respond en force and make our congressional leaders aware of these concerns as well.