The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) announced July 29 the outcome of its investigation into a May 9, 2024, allision between the tow of the mv. Joe B. Wyatt and a protection cell and fendering system of the Fort Madison Bridge, located at Mile 384 on the Upper Mississippi River near Fort Madison, Iowa.

The Joe B. Wyatt, built at St. Louis Ship in 1982 and owned and operated by Ingram Barge Company, was downbound and pushing 13 loaded hopper barges and a pair of empty tank barges when it approached the Fort Madison Bridge just after 1 p.m. on the day of the allision. According to the NTSB report, the Joe B. Wyatt had departed Consolidated Grain & Barge’s facility near Mile 418 on the Upper Mississippi that morning at about 4:45 a.m. The overall tow length was 1,153 feet. At its widest, the tow measured 105 feet.

The Joe B. Wyatt carried a crew of eight. The captain and pilot aboard the Joe B. Wyatt followed a six-on, six-off schedule, with the captain standing watch from 5:15 to 11:15 and the pilot standing watch from 11:15 to 5:15 around the clock. Thus, the pilot was at the helm as the Joe B. Wyatt approached the Fort Madison Bridge.

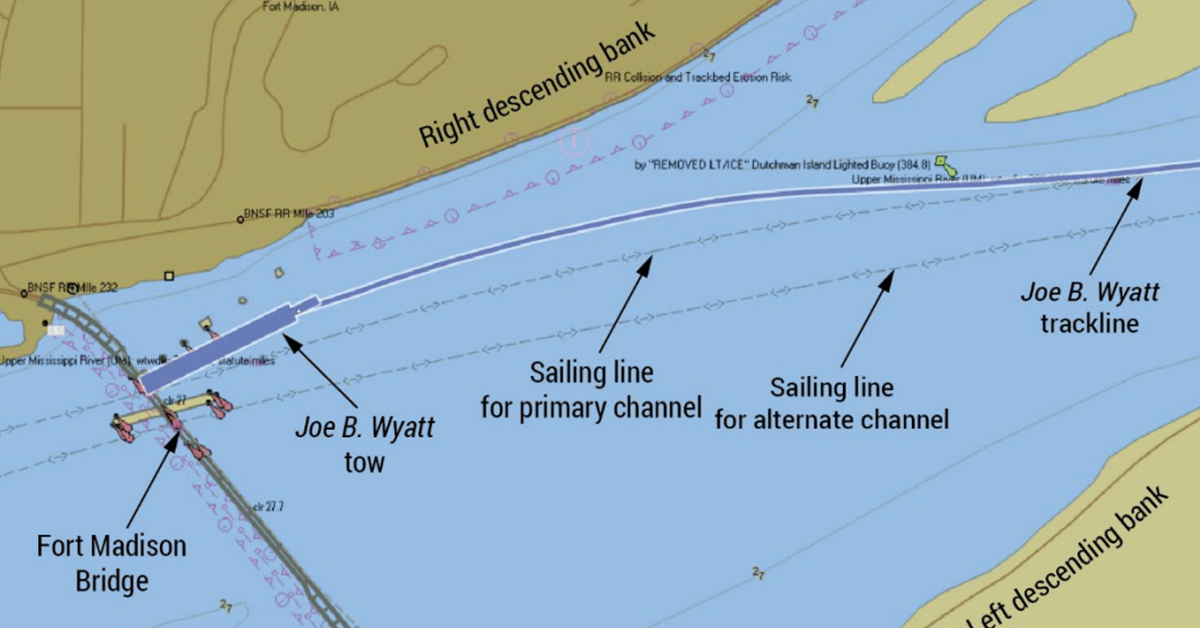

At about 1:06 p.m., the Joe B. Wyatt passed the southwest end of Dutchman Island, about a mile upriver of the Fort Madison Bridge, traveling at a speed of 8.2 mph. According to the NTSB report, the vessel and its tow were about 65 feet to the right of the “charted primary sailing line” at the time. The NTSB report notes that a portion of the river splits off to form Dutchman Island. “This configuration could create a cross-current for vessels attempting to navigate through the Fort Madison Bridge,” the report stated.

“Anticipated that a current coming from around Dutchman Island would set the tow toward the left descending bank, the pilot intentionally steered the tow to the right of the primary channel sailing line,” the NTSB report stated.

As the vessel and its tow approached the bridge’s 200-foot-wide primary channel, the Joe B. Wyatt was as much as 226 feet to the right of the sailing line. At about 1:08 p.m., the pilot realized the anticipated cross-current “wasn’t holding [him] up” as expected. The pilot increased power “to attempt to maneuver the tow back toward the center of the channel,” the NTSB stated. At about 1:11 p.m., as the tow passed the upriver end of the bridge’s fendering system, the Joe B. Wyatt was about 210 feet to the right of the sailing line and traveling at 9.8 mph.

About a minute later, as the lead port barge drew near to the sailing line, the third barge on the starboard side of the tow “contacted a protection cell located at the base of a bridge pylon and began to slide along its side,” the NTSB report stated. Within moments, the head of the tow struck a protection cell, abruptly stopping the Joe B. Wyatt’s forward momentum and causing the tow to break apart. Thirteen of the 15 barges drifted downriver with two deckhands aboard. One barge partially sank. Damage to the barges, protection cell, fendering system and the Joe B. Wyatt was estimated at $3.28 million.

The NTSB found that the pilot at the helm had slept about 12 hours within the previous 24 hours, meaning fatigue, impairment or distraction did not play a role in the allision. Rather, the NTSB concluded the pilot overcompensating for anticipated river crosscurrents was the probable cause. For lessons learned, NTSB noted that a charted sailing line can be used “as a guide, along with the mariner’s own experience and assessment of the existing circumstances.”

Featured image caption: An illustration of the sailing line and allision of the mv. Joe B. Wyatt and a protection cell at the Fort Madison Bridge on the Upper Mississippi River near Fort Madison, Iowa, on May 9, 2024. (NTSB graphic)