As the summer of 2025 has wound down, the refrain from the Turnpike Troubadours song “Long Hot Summer Day” comes to mind.

For every day I’m workin’ on the Illinois River

Get a half a day off with pay

Old towboat pickin’ up barges

On a long hot summer day

The song, originally written by John Hartford in 1976 and released by Turnpike in 2010, captures the essence of a towboat worker’s life on the Illinois River during the summer season.

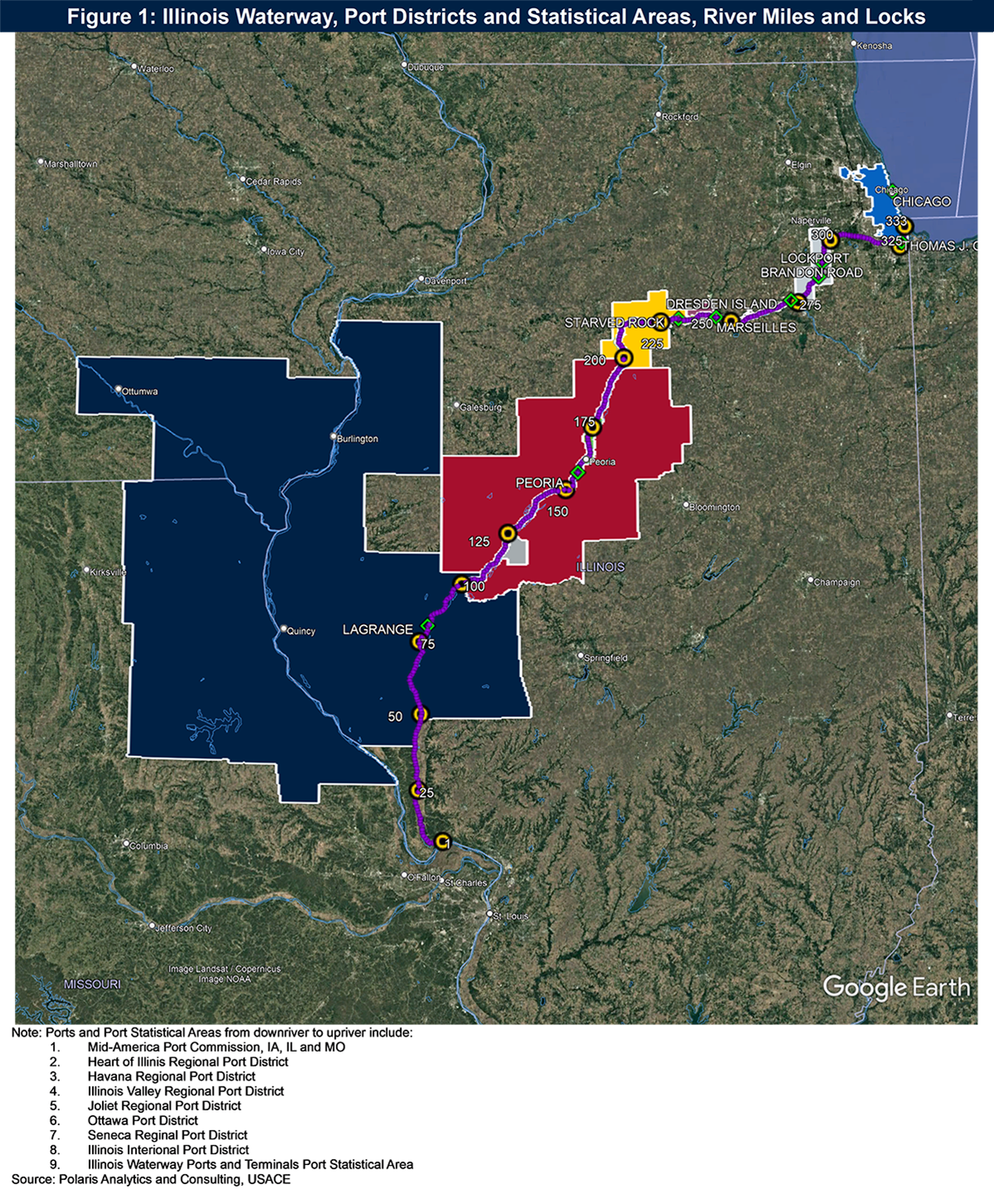

The Illinois River is a 333-mile waterway connecting the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River Basin through a series of eight locks, essentially between Chicago and St. Louis. The waterway traverses the rich, productive farmland of Illinois, serving nine port districts along the way as shown in Figure 1.

While Hartford’s verse communicates the rhythm of life on the river, that rhythm has changed. In recent years, towboaters have had fewer barges to move, reflecting a broader decline in commodity volumes on the Illinois Waterway.

Well, I’m gonna pick up some of these empties, Lord

As soon as I find where they lay

Tied off them jolly and leavin’ lines

On a long hot summer day, yeah!

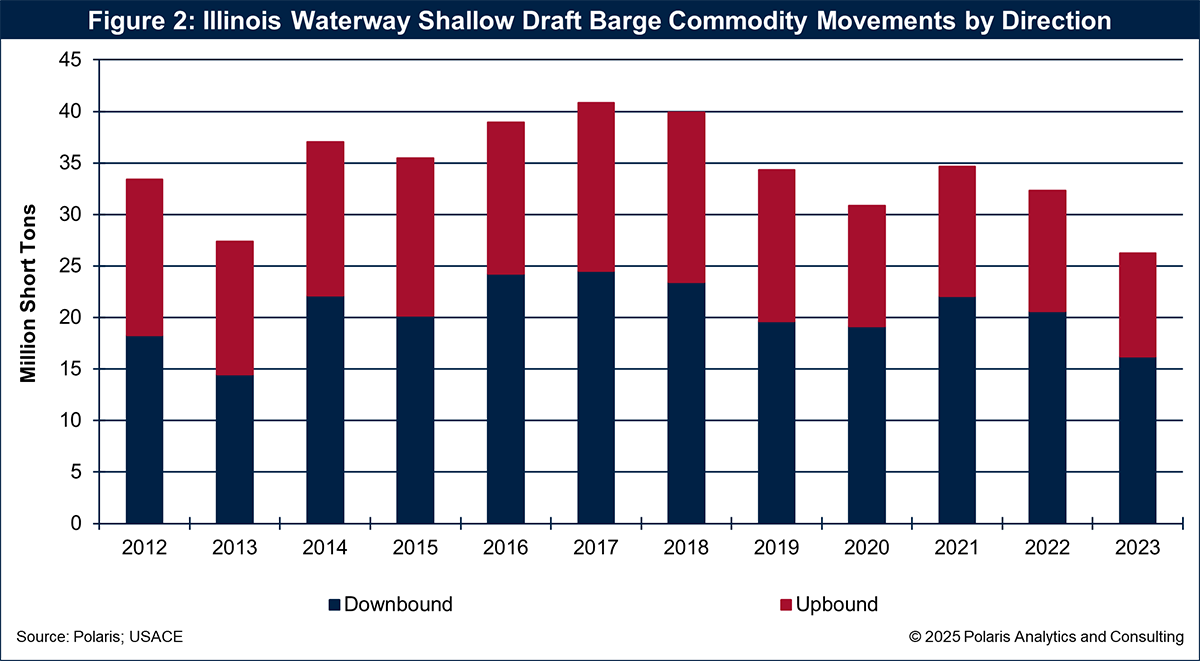

Unfortunately, in recent years, towboaters have had fewer empties to pick up to be loaded at a berth, terminal or port or put into a tow. Since peaking at 40.9 million short tons of commodity volumes moved by barge in 2017, cargo volumes on the Illinois Waterway have dropped nearly 36 percent as of 2023, the most current data available through the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Barge volumes on the waterway have averaged 34.3 million tons since 2012.

On average, 60 percent of the barge volume on the Illinois Waterway moves downriver, while 40 percent moves upriver. The volume of commodities and direction of travel moved by barge on the Illinois Waterway is shown in Figure 2. These directional trends set the stage for a deeper look at what is moving—or not moving—on the waterway as discussed in the next section. The types of commodities transported reveal how weather, policy and global competition have reshaped the river’s role in trade.

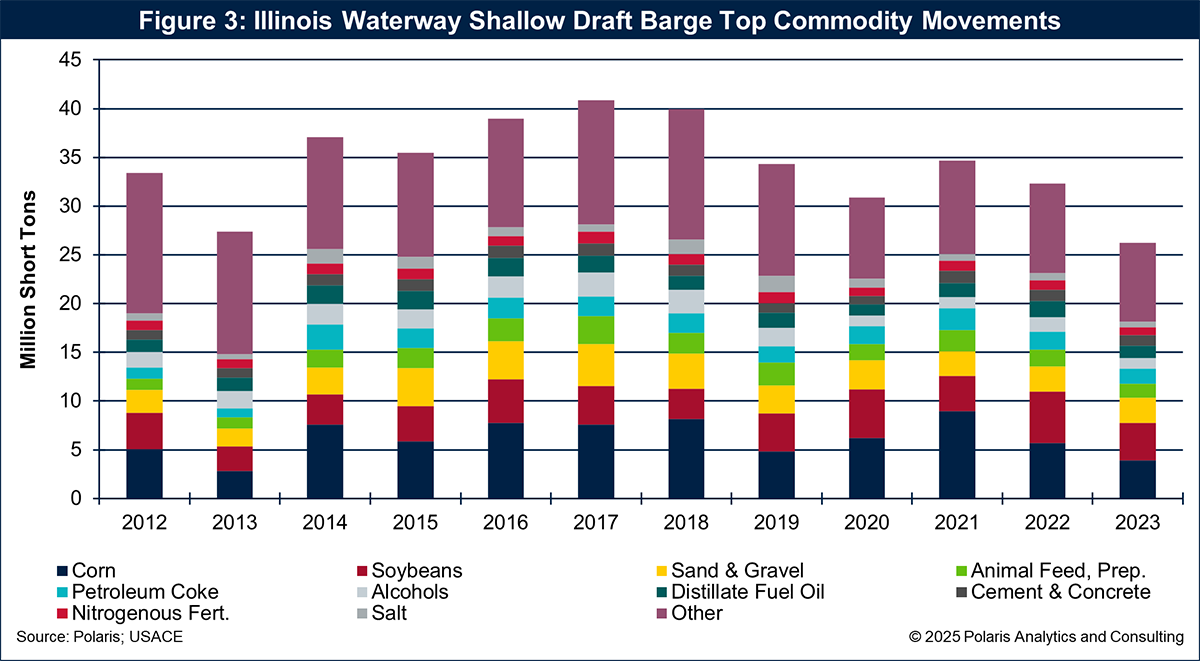

The commodities moved by barge on the Illinois Waterway are the building blocks of industry, commerce and trade. Since 2012, there have been 95 different commodities moved by barge on the waterway, averaging 71 different commodities during any given year.

Given the path the waterway travels, the top commodities moved by barge are agricultural-oriented: corn, soybeans, prepared animal feed (e.g., soybean meal and distillers’ dried grains with solubles), alcohols (ethanol) and fertilizers.

However, the supply of those commodities is influenced by weather, such as a drought-reduced harvest in 2012 that affected movements through 2013 and something similar in 2022. The demand for agricultural commodities is influenced by policy, including trade tariffs that affected movements from 2018 to 2020. Importantly, competition elsewhere in the world is up, taking market share from the United States.

The movement of corn exceeded 8 million short tons in 2018 and totaled nearly 9 million in 2021. However, volumes plummeted in 2022 to 5.6 million short tons and further still to less than 4 million in 2023. Soybean movements experienced a similar drop over that time period, especially related to the U.S.-China tariff dispute in 2018 to 2020.

Commodities used to build the economy include sand and gravel, cement and concrete, and steel products. Distillate fuel oil is another commodity that help drive the economy, while salt is used to keep the economy moving during the winter (and for food and other industrial uses). Salt is also the feedstock for de-icing fluid used on airplanes at O’Hare International Airport and Midway Airport, for example.

Coal was a prominent cargo, exceeding 2 million short tons in 2012, but falling to less than 100,000 tons in 2020—a drop of 97 percent. Carbon emission reduction policies have severely changed coal movements by shifting away from coal consumption to other energy sources. Unless there is a radical policy reversal supporting coal use, its volumes will remain negligible on the Illinois Waterway.

The top commodities moved by shallow draft barge on the Illinois Waterway are shown in Figure 3.

Ports Feel The Brunt Of Commodity Shifts

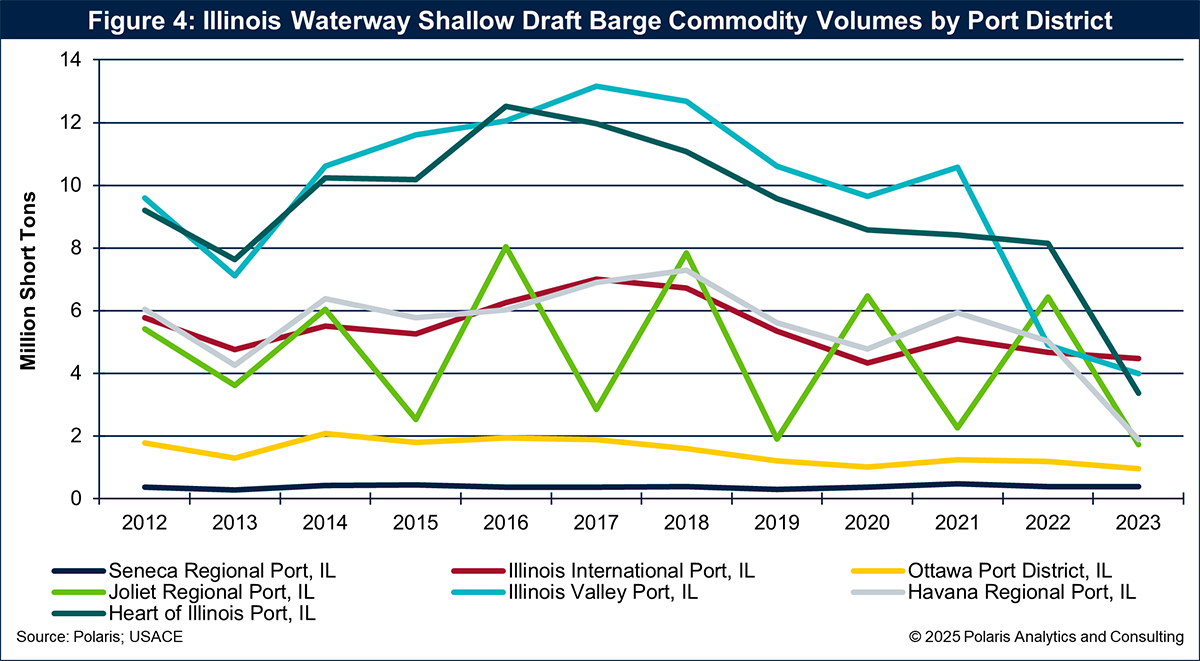

While commodity trends tell part of the story, their impact is felt most acutely at the local level. The nine ports along the Illinois Waterway have experienced the brunt of these shifts, with some seeing dramatic changes in volume. While the Mid-America Port encompasses a part of the Illinois Waterway, its barge volumes are largely on the Mississippi River. The Illinois Valley Port and the Heart of Illinois Port have historically reported the highest reported commodity volumes on the Illinois Waterway.

Commodity volumes through the Illinois Valley Port have averaged about 10 million short tons since 2012. However, because agricultural and coal are leading commodities through the port, its volumes dropped to less than 4 million short tons in 2023.

Through the Heart of Illinois Port, commodity volumes have averaged about 9 million short tons since 2012. In 2023 commodity volumes totaled 3.4 million short tons, or about a third of the historical average.

Commodity volumes through the Joliet Regional Port are erratic from year to year, gaining an average of 4.3 million short tons during rebound years while dropping an average of 4.2 million during off years. Sand and gravel are the highest volume commodity for Joliet Regional Port, followed by petroleum coke. For those commodities and others, it appears there is a data reporting issue, with volumes reported in one year and nothing in the following year.

The Illinois International Port and Havana Regional Port have similar volumes from one year to the next, ranging from about 5 million short tons to 7 million short tons.

The volume of commodities moved by port on the Illinois Waterway are shown in Figure 4. These port-level figures underscore the challenges facing the Illinois Waterway. Despite the headwinds, though, there are promising signs that the waterway can reclaim its role as a vital link in America’s supply chain.

While barge commodity volumes have suffered due to policy and weather, opportunities abound to reclaim lost ground. However, doing so will require overcoming green policy (which affects coal movements) and trade policy (which affects agricultural movements). Unlike coal, agricultural commodities have market opportunities despite trade tariff disputes between the United Stats and China, a historically important market for U.S. crops such as soybeans.

U.S. corn exports for the 2025-2026 crop marketing year are forecast reach record levels, pushing total grain and soybean exports toward the fifth (and quite possibly the fourth) largest in U.S. history. Nearly 60 percent of U.S. grain and soybean exports move through export grain elevators in the Center Gulf on the Mississippi River Ship Channel, with nearly all that volume arriving by barge from the Upper Mississippi River, Illinois Waterway and Ohio River.

In recent years, the maritime industry, particularly through efforts of Waterways Council Inc. and commodity associations, together with Congress and the Corps, have been working to modernize locks and dams on the Illinois Waterway. Those efforts have led to navigation stoppage for necessary work at the locks. The work continues, and it’s important that the work is completed to assure industry and markets that the Illinois Waterway is a reliable and viable transportation artery.

To seize these opportunities, coordinated action is essential. Initiatives like the Illinois River Cities and Towns Initiative are laying the groundwork for a unified approach to infrastructure, investment and advocacy.