Bill Holman didn’t need the words on the plaque at Lock 2 Park in Nashville, Tenn., to know its historical significance.

Holman, 91, lived through it.

“This means so much to me,” he said at a ceremony June 24 to unveil the marker. “It’s really dear to my heart because I was born here. My mother and dad transferred from Lock C here to Lock 2 in either 1927 or early ’28. The house set right there, just between the tree and that playground.”

From 1888 until 1928, the Nashville Engineer District struggled against all odds to create a system of locks and dams along the Cumberland River. Eventually, the Corps built 15 of 26 planned navigation locks on the river. Those downstream from Nashville were lettered A through F. Those upstream were numbered, 1 through 8 and 21. Constructing them meant using a wooden cofferdam, hand tools and A-frames as well as animals to haul in supplies and stone blocks on tracks from a rock quarry.

Lock 2, in what is known as Pennington Bend, was built between 1892 and 1907. The shoreside wall of the lock chamber and one lock-keeper house remains, along with some concrete steps. The park has been a partnership between the Corps and the parks district since 1956, since even before the county and city merged into a metropolitan government system in the 1960s.

Holman’s father, known as “Red” Holman, worked for the Corps and lived in one of the lock-keeper houses on the property, one of which remains.

The houses were identical inside. Outside, they differed in but one thing: the stairs to the back porch. On the remaining house, Holman said, the staircase went down a few steps and turned. On the one where he was born, it was 13 steps straight down.

He remembers that number exactly, just exactly as he does the flood of 1937, when the water came up to the second step from the top, and the family had to leave in a rowboat.

Floods were a regular occurrence, he said, though not as big as that one.

“We got flooded almost every year,” he said. “Down below the reservation was a slough that backed up with water. When the water would rise, it would get across the road out here.”

The workers would park their cars up on top of the hill, but Holman still needed to get to school, so his father would take him across the flooded road in a rowboat, and he would walk the rest of the way.

“As the water would rise it would get across the road in another place,” Holman said. “He would put me across in a skiff, and we would walk to the other place, and he’d put me across in another skiff, and I’d walk on to school.”

When the water rose even higher, he said, it was too far to row every day. Instead, his father would row him across on Monday morning, and he would stay every night with a neighbor until his father picked him up in the boat again on Friday after school.

Holman also remembers the difficult period of World War II, when the Corps installed a gate at the end of the road. No one who didn’t live or work at the lock was allowed on the property, which means Holman had to meet his buddies outside the gate to play. Luckily, he said, his mother would make the trek down the yard and out the gate to bring them cookies.

There were lots of good times.

“This was a place of gathering on Saturdays and Sunday afternoons,” Holman said. “People thought it was the greatest place, which it was. There was a croquet yard right there, and they played croquet from sun up to sun down sometimes.”

Holman was drafted in 1950 and served in the Korean War. While he was away for his military service, his father became lockmaster and moved into the other house, the one that still stands.

“That was my bedroom until I got married in August of 1954,” he said, pointing toward a corner of the house.

His father continued living at the lock until 1956, when he retired not long before Lock 2 closed permanently. The Corps constructed modern, multi-purpose dams from the 1940s through the 1970s, which replaced the need for the Corps of Engineers to maintain and operate the old locks and dams.

Memories like Holman’s help to preserve the history the Corps, Metro Parks and the Metro Historic Commission saw when they placed Lock 2 Park on a priority list for receiving a historic marker.

Jeff Syracuse, the Metro Council member representing district 15, in which the park lies, said it is a unique place that continues to be appreciated by those living nearby.

“This park here is a very special place to a lot of neighbors,” Syracuse said. “It’s a very special partnership between Metro Parks and the Corps of Engineers.”

Lt. Col. Sonny Avichal, Nashville Engineer District commander, pointed out that it was the desire to make the Cumberland River navigable that led to the formation of the Corps district in 1888.

“There was a huge desire and a need to transport goods and commerce up and down the river,” he said.

By the end of June 1889, the site of Lock and Dam No. 2 and the lock keeper’s house had been approved by the chief of Engineers, and negotiations were in progress for the purchase of the land at “Becks Ripple,” about 12 miles upriver from Nashville, said Lee Roberts, public affairs specialist with the Nashville Engineer District. In 1891, however, excavation revealed that suitable bedrock foundation at the site did not exist at a consistent depth, leading to the selection of another site.

In March 1894, the Corps decided to construct Lock 2 at its eventual site, about 1-1/2 miles below the one originally considered. Construction began in late April of that year.

By the end of June 1906, the filling valves and maneuvering appliances had been placed in the lock, Roberts said.

An unusually high stage of water in the river and a lack of labor delayed the installation of the lock gates until November. Construction of the dam began August 13, 1906. The Corps completed the dam and put the lock into operation October 9, 1907.

“These old locks at first were entirely manually operated,” Roberts said. “It took three or four guys to open gates and to fill or empty the water out of the locks with the valves. At some point they did get some mechanical help with that.”

The lock reservation itself was a small community, complete with kitchen, dining room and blacksmith shop, along with quarters for the men who worked there.

Over time, the vessels hauling goods up and down the river got bigger and bigger, and tows had to be split, taking up valuable time and resources. As the new locks and dams went into service, the old ones were demolished.

“All of those locks are long gone, and the river itself is much wider and deeper than anybody had originally ever thought of as ships got larger and larger,” Avichal said.

Pennington Bend is now part of the pool created by Cheatham Lock and Dam in Ashland City, west of Nashville.

Avichal pointed out the importance of the partnerships that have made the Corps’ missions, including that of creating locks and dams for navigation, flood control and hydropower generation, successful ones. As with placing the marker, he said, the Corps will continue to work in partnership with communities along the rivers, find ways to celebrate the past and continue to prepare for the future.

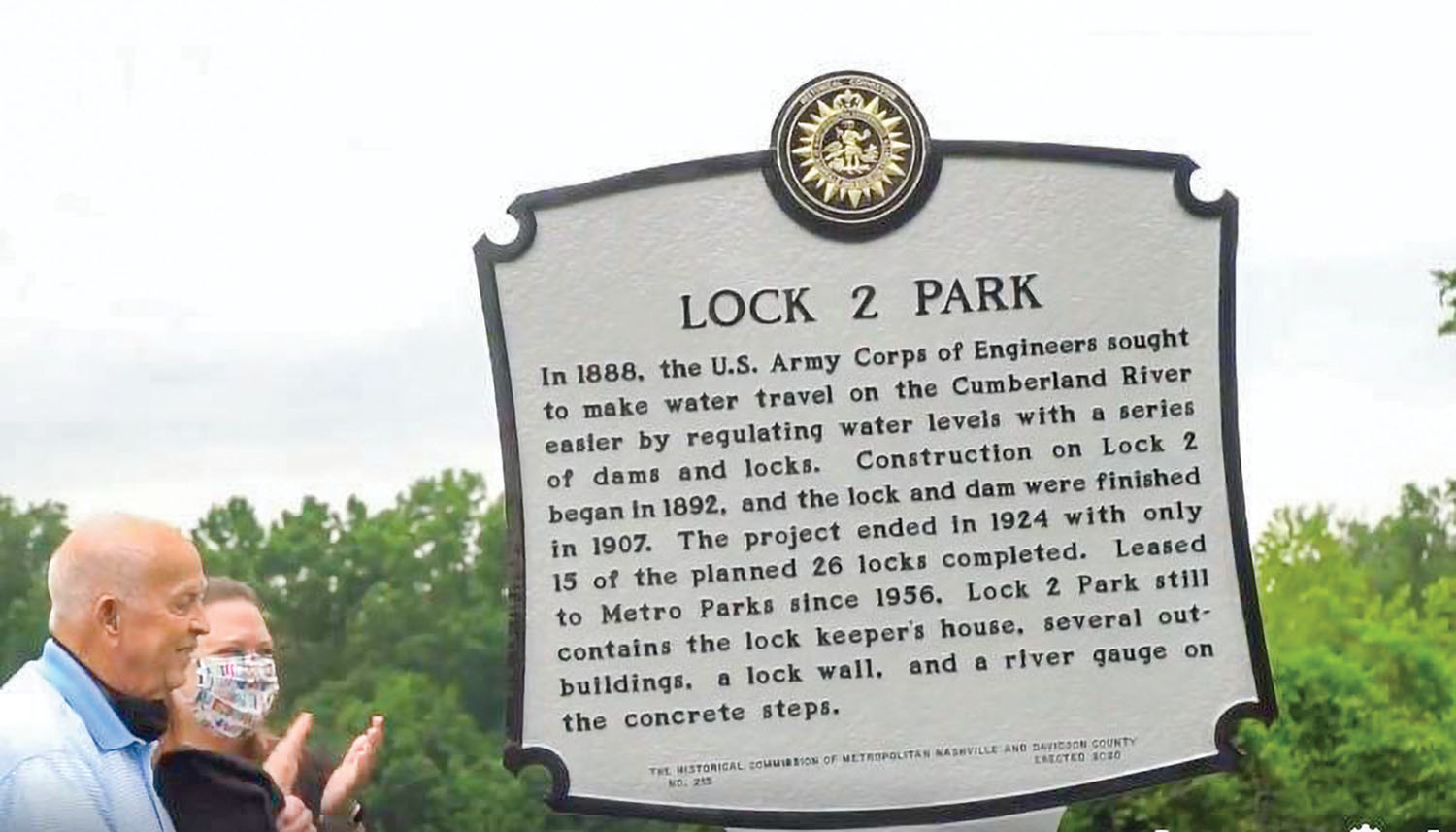

Lock 2 Park now also commemorates these accomplishments with the words on the historic marker, unveiled at the conclusion of the ceremony, which was open to in-person guests as well as broadcast online to a wider audience. The marker reads, “In 1888, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers sought to make water travel on the Cumberland River easier by regulating water levels with a series of dams and locks. Construction on Lock 2 began in 1892, and the lock and dam were finished in 1907. The project ended in 1924 with only 15 of the planned 26 locks completed. Leased to Metro Parks since 1956, Lock 2 Park still contains the lock-keeper’s house, several outbuildings, a lock wall and a river gauge on the concrete steps.”

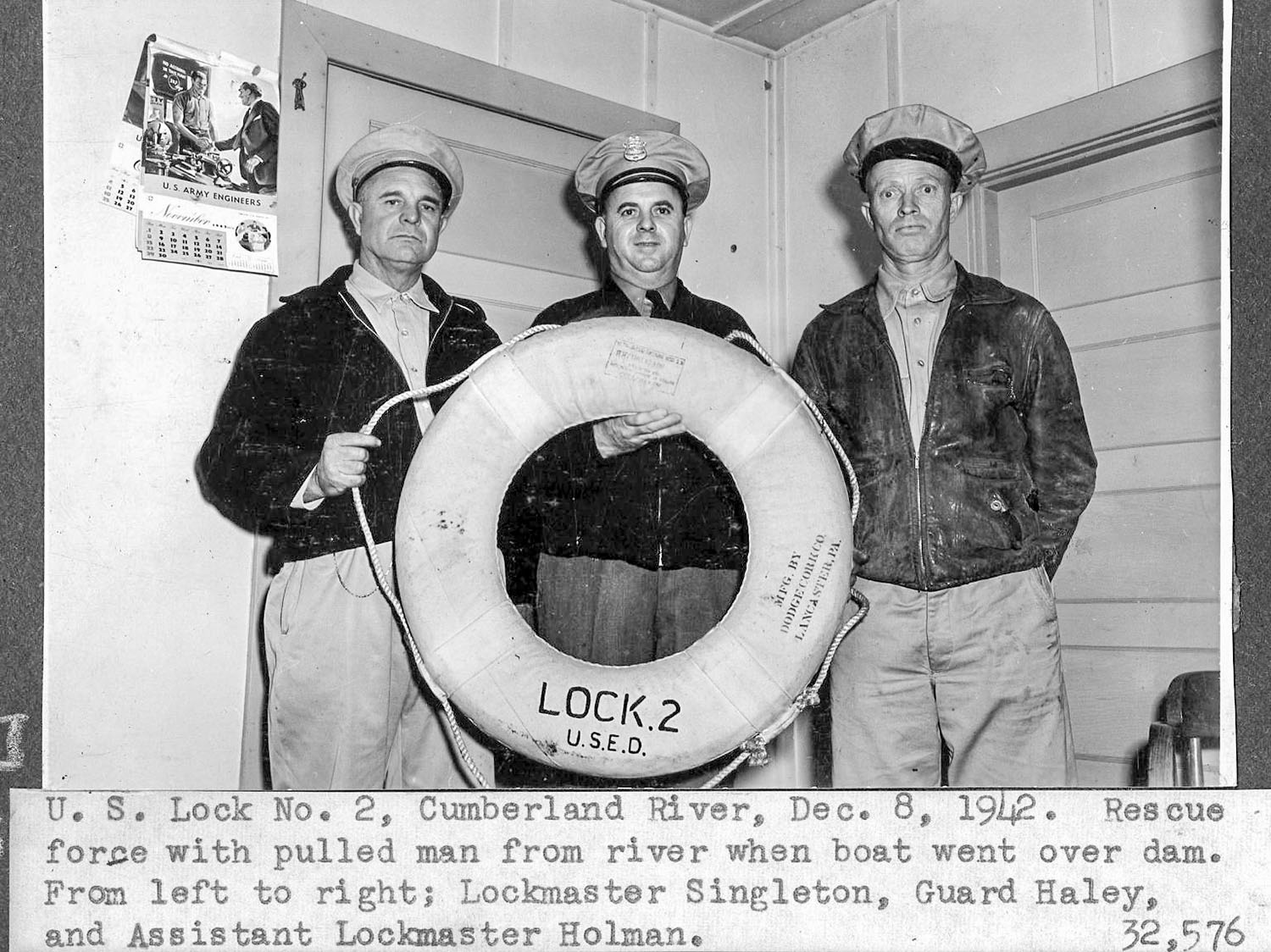

Caption for top photo: From left, Lockmaster Singleton, Guard Haley and Assistant Lockmaster Red Holman of the Nashville Engineer District pose after rescuing a man when his boat went over Dam 2 on the Cumberland River in Nashville, Tenn., December 8, 1942. (Nashville Engineer District historic photo)