As the Mississippi River winds past Memphis, Tenn., its mighty flow, averaging 593,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), or roughly 4.45 million gallons per second, supports navigation, ecosystems and communities. Yet, whispers of a threat have emerged. Data centers, the backbone of artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud computing, are accused of guzzling water from the river and its tributaries, potentially worsening low-flow conditions that already challenge barge operators and communities.

But is this true? Using xAI’s Colossus supercomputer in Memphis as a case study, let’s dive into the reality of data center water use and its negligible impact on the waterways.

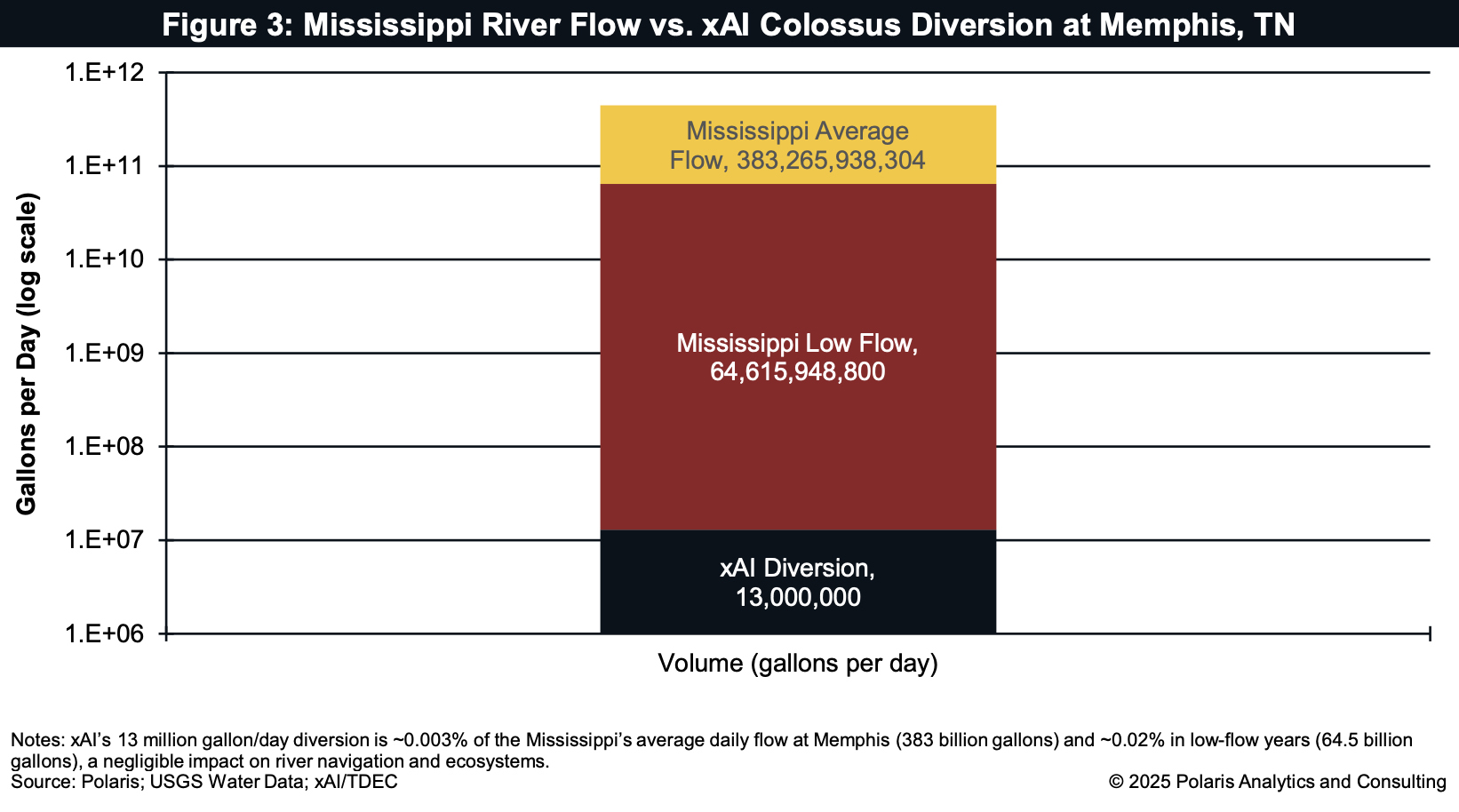

The myth stems from the sheer scale of modern data centers. Globally, these facilities consume an estimated 1 billion to 2 billion gallons daily for cooling servers that power AI, streaming and cloud services. That figure is drawn from reports by major operators like Google (15 million gallons daily), Microsoft (4.6 million) and Meta (about 2.2 million), plus thousands of smaller facilities. With the Mississippi’s flow dipping to 100,000 cfs, or about 64.5 billion gallons daily, in drought conditions, it is easy to fear that data centers could exacerbate low-water woes, impact barge movements or stress local municipal water intakes.

However, direct withdrawals from the Mississippi are rare. Regulatory hurdles, like the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation’s Aquatic Resource Alteration Permits (ARAP) and oversight from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, make river intakes costly and complex due to sediment, pollutants and ecological concerns. Instead, data centers lean on groundwater or reclaimed wastewater, as seen in Memphis.

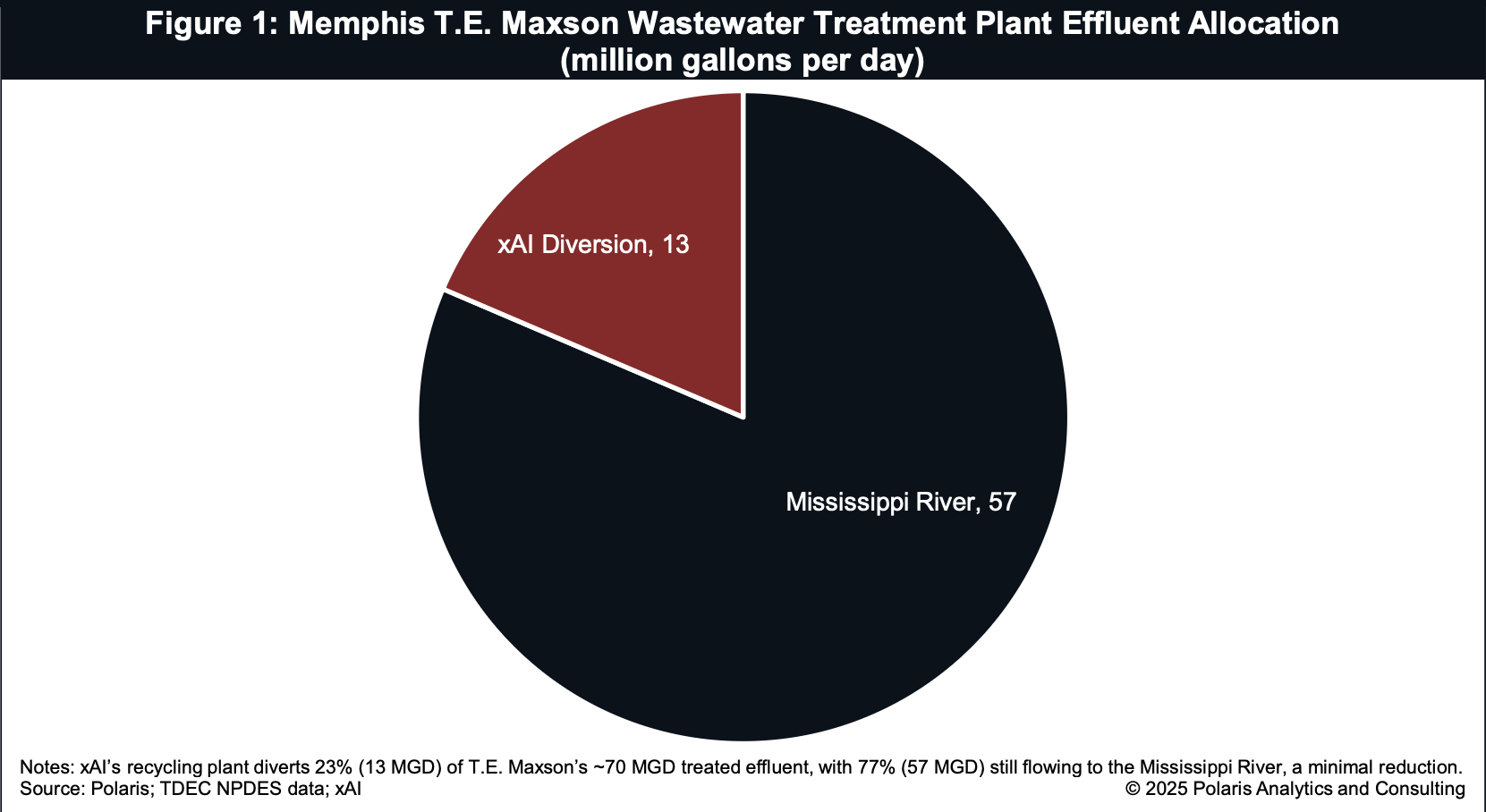

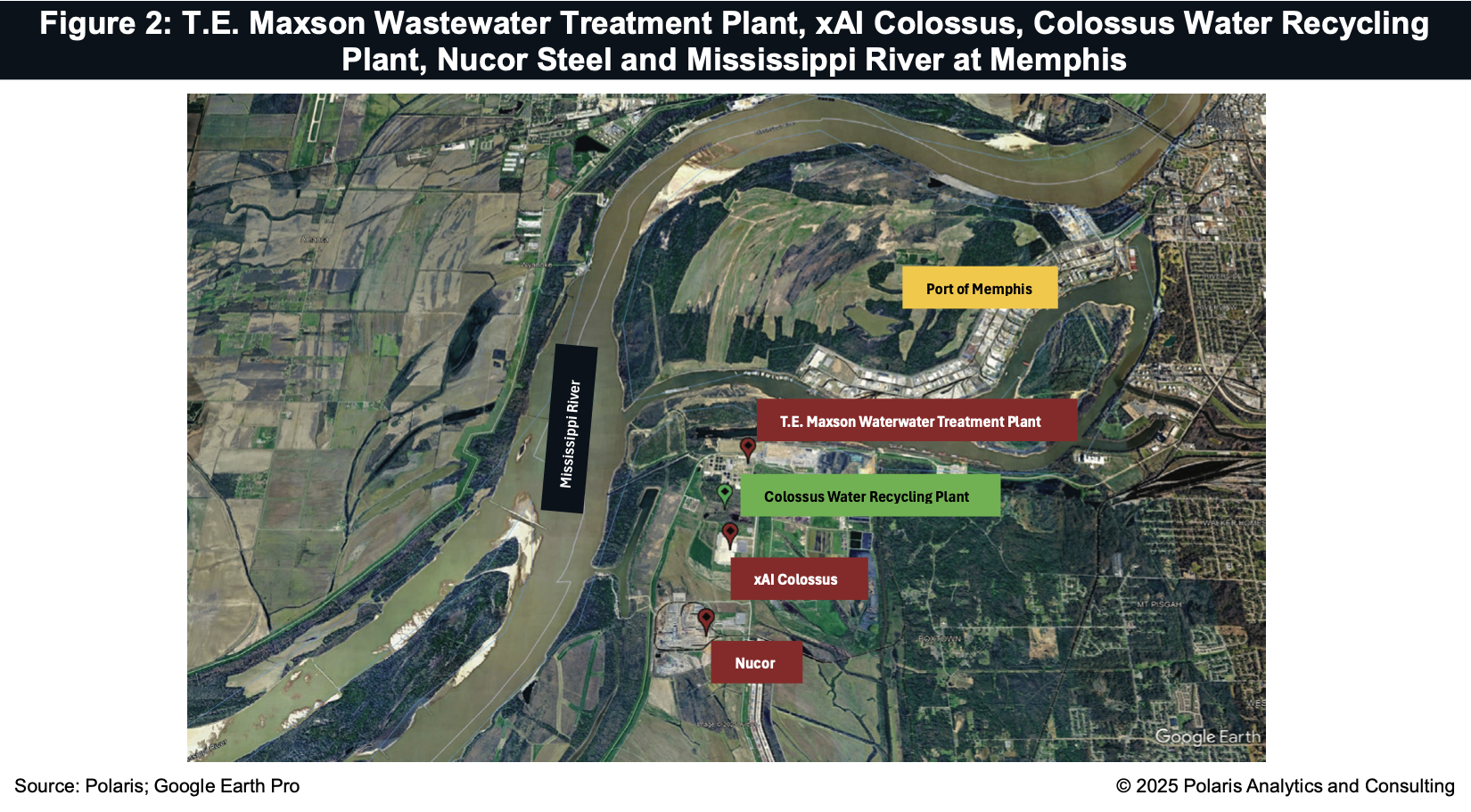

Enter xAI’s Colossus, recognized as the world’s largest AI supercomputer, humming in south Memphis with more than 200,000 Nvidia GPUs (and eventually increasing to 1 million). Its cooling needs are immense, requiring up to 13 million gallons per day to keep chips from overheating. Currently, it draws 1.3 million gallons per day from the Memphis Sand Aquifer, but xAI plans to tap another source: an $80 million Colossus Water Recycling Plant that broke ground on October 10 and will be operational during late 2026. This facility will pull 13 million gallons daily of treated effluent from the nearby T.E. Maxson Wastewater Treatment Facility, which processes about 70 million gallons a day of municipal wastewater—water that would otherwise flow into the Mississippi River as shown in Figure 1. The T.E. Maxson Wastewater Treatment Facility, Colossus Water Recycling Plant, xAI Colossus, Nucor, the Port of Memphis and the Mississippi River are shown on the map in Figure 2.

Here is where math matters. Maxson’s effluent, if not diverted, adds about 70 million gallons per day to the Mississippi River. xAI’s diversion of 13 million gallons per day reduces this by about 23 percent, or 4.7 billion gallons annually.

Sounds big, right? Not against the Mississippi River’s scale.

At 593,000 cfs, the river carries about 383 billion gallons daily past Memphis. xAI’s diversion is a mere 0.003 percent of that flow as shown in Figure 3, akin to a drop in a bucket the size of Beale Street. Even in low-flow conditions (100,000 cfs), the impact remains negligible, ensuring no threat to navigation or ecosystems.

Still, concerns linger. Groups like Protect Our Aquifer and Memphis Community Against Pollution have raised alarms about indirect flow reductions and cumulative impacts, like air emissions from Colossus’s backup turbines. xAI counters with its zero-discharge design, no wastewater returns to sewers or the river and aquifer savings of 9 percent to 10 percent for Memphis’s groundwater. TDEC’s weekly monitoring ensures compliance, and the plant’s surplus water may even aid nearby partners like Nucor Steel.

This issue is not unique to Memphis. Amazon Web Services’ data center in Madison County, Miss., uses reclaimed wastewater from Beattie’s Bluff, saving 80 million gallons of drinking water yearly without touching the Big Black River. Across the United States, data centers are shifting to closed-loop cooling and recycled water to minimize river reliance, a trend likely to grow as AI demand doubles water needs by 2028.

For the waterway communities and the maritime industry, the takeaway is clear: data centers like Colossus are not draining the Mississippi, but they are reducing the flow. Their water use, while significant, is a fraction of the river’s flow, and innovative recycling, like xAI’s plant, will keep impacts low.

Still, vigilance is key. Supporting TDEC’s oversight and pushing for transparent water use reporting will ensure tech growth does not compromise river flows. As AI reshapes the world, Memphis is demonstrating it can coexist with healthy waterways, as long as sustainability and accountability are prioritized.