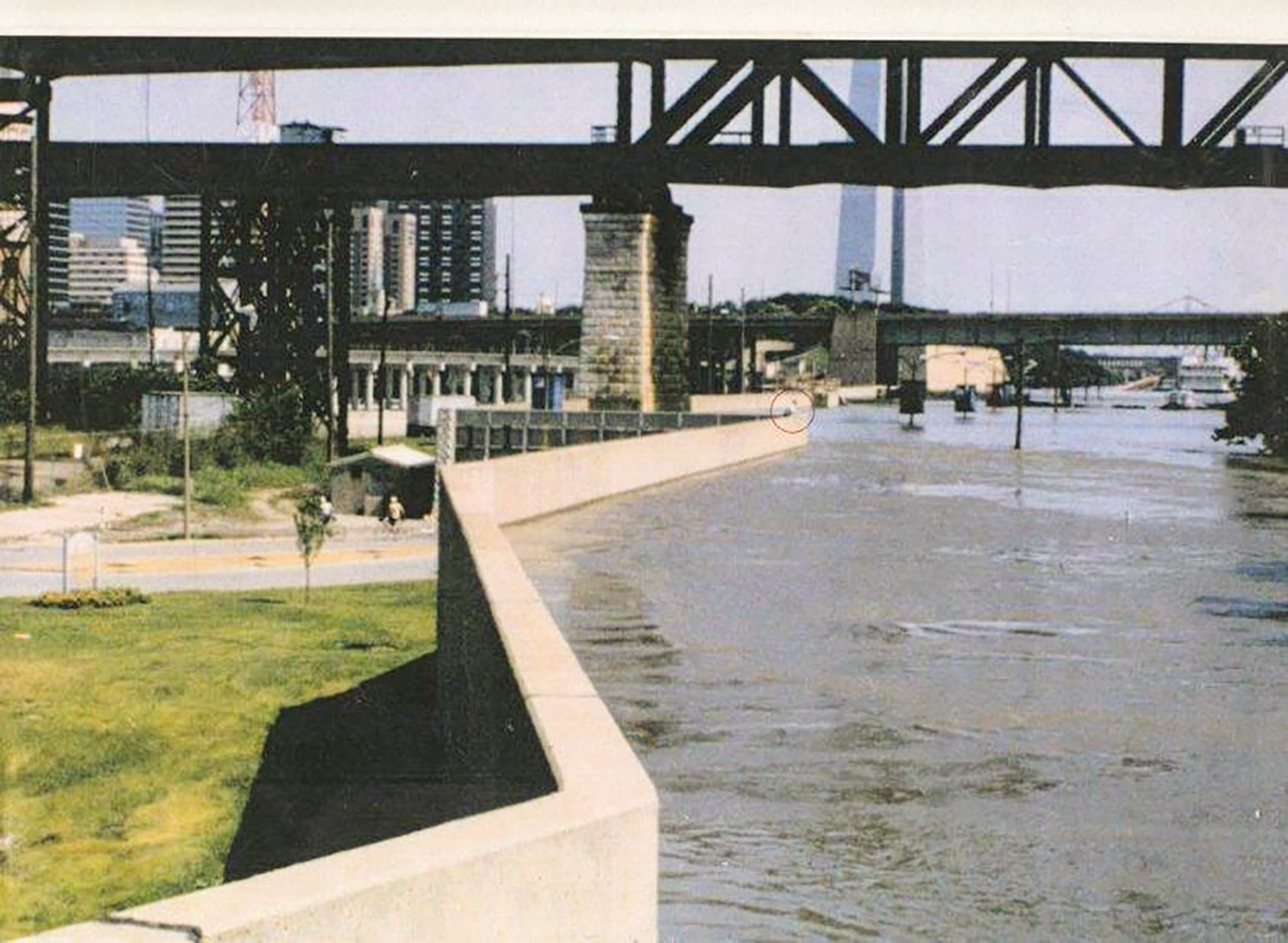

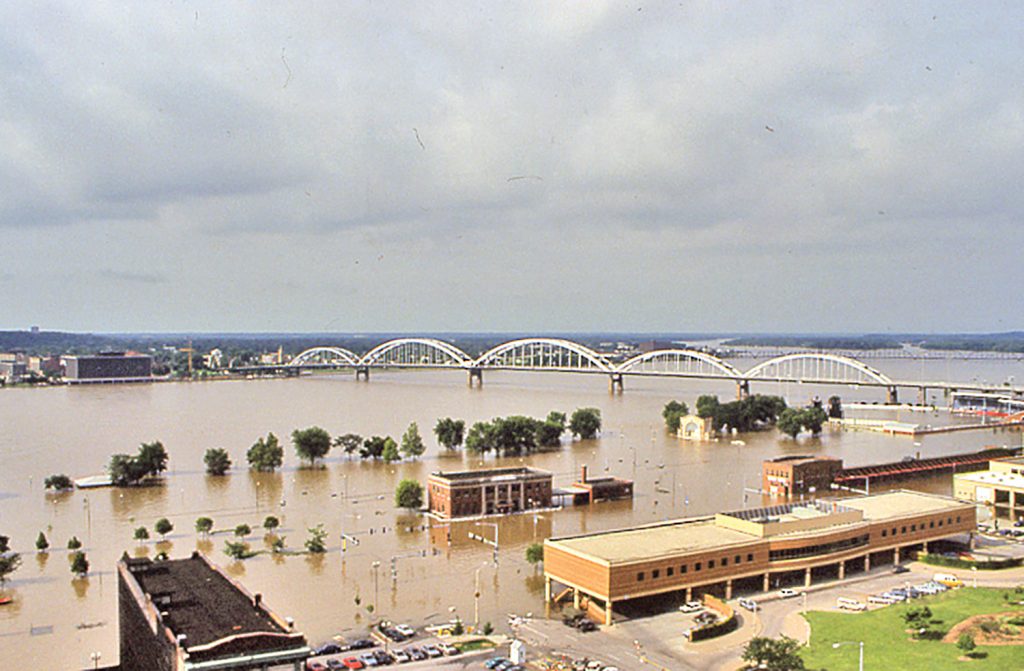

Twenty-five years ago this week, the Mississippi River reached its highest point in recorded history on the St. Louis gage. With the river only a few feet below the top of the St. Louis floodwall and smaller levees overwhelmed throughout the region on the Missouri and Mississippi rivers, the Flood of 1993 wreaked havoc on Midwestern river towns, with billions of dollars in damages and dozens of lives lost.

On August 1, 1993, the levee near Columbia, Ill., (just across from St. Louis) broke and the river crested, causing 47,000 acres of land to be flooded. A couple of days later, officials decided to break through the stronger Mississippi River levee to allow the water back into the river. The plan worked, and although some residential areas were flooded, many were saved.

The impact the flood had on the inland river navigation industry resulted in a daily loss of nearly $2 million in commerce after Coast Guard officials shut down commercial operations on the river in early July.

The flood, which lasted in some areas until October of that year, saw nearly all of the 700 privately built agricultural levees overtopped or destroyed along the Missouri River.

The St. Louis Engineer District deployed more than 140 people to the field, where they spent weeks working with local communities to shore up levees as the river continued to rise. In some areas, the Corps’ flood-fighting attempts were successful, while no amount of effort could hold the raging river back in others.

Feeding The Beast

Dave Busse, chief of engineering and construction for the St. Louis District, was working in the district’s Water Control Office the summer of 1993. As the water control manager, Busse worked closely with projects such as flood control reservoirs and forecasting river levels. While the National Weather Service (NWS) is the official forecasting organization, the Corps’ Water Control Office is also required to do forecasts to assist the navigation industry and flood teams.

“We were in the midst of uncharted territory for everyone involved,” said Busse about the historic flood, which was 6 feet above the previous all-time record of the 1973 flood. Despite the unique nature of the flood, Busse said the Corps was able to correctly forecast that the river would go above 49 feet in St. Louis a week before the NWS did.

“Forecasting the Flood of 1993 was different, because most models are calibrated to past events, but there had not been a past event that came close to the magnitude of what we were dealing with at the time,” said Busse. “That caused a lot of problems with river forecasts for some agencies. For example, what typically happens on the Missouri River is that when a large flow of water comes out of Kansas City, Mo., most of that water doesn’t make it all the way to St. Louis due to numerous agricultural levees between the two cities.”

A primary factor leading to the flood, said Busse, was a prolonged period of heavy rainfall and an already saturated ground along the river system. The excess water far exceeded the design and capabilities of most of the lower Missouri River’s agricultural and non-federal levee, which were quickly overcome by the rising water.

“I have never witnessed a flood of that magnitude,” said Busse. “It just rained for an entire month, with flooding beginning around Easter of that year. Heavy and long-lasting rain in Iowa continued to feed the beast until it was no longer a typical system, and we had to do away with our computer models for forecasting and did the math ourselves.”

Breakthrough Forecast

While various agencies, including the NWS, were working around the clock to track the flood and forecast its next moves, Busse said the Corps’ Water Control Office was busy scribbling math equations on a chalkboard. The office’s phones were ringing off the hook with people questioning their forecasts. “There was a lot of doubt that our forecasts were accurate,” he said. “One of our colleagues said that our forecasts were statistically impossible, and we were going to make fools of ourselves if we stayed with the forecast we came up with because, to them, it seemed impossible that the water would get as high as it eventually did. Looking back, it seems obvious, but amid the flood, almost no other forecaster was coming up with the numbers that we were.”

Fortunately for Busse and his colleagues, leadership in the St. Louis District had faith in their numbers. “It would have been easy to go with what all the other agencies were forecasting, but the district trusted us,” he said. “And we ended up being right. The Corps’ reputation for forecasting flooding events really grew because of that moment. We have a lot of river stakeholders who, to this day, come to us for a forecast. The NWS is great, but a lot of people remember what happened in 1993 and we were a part of that.”

Recovery Efforts

Fred Joers, chief of the Inland Navigation Design Center with the Rock Island Engineer District, was stationed at the reservoir on the Upper Mississippi River in Iowa, where he assisted in recovery efforts throughout the flood. He and his team monitored the levees and checked for seepage or problem areas in the Quad Cities.

He also helped eliminate vibrations caused by the high volume of water at the area dam that led to cables breaking on the tainter gates. At the time, Joers was employed by the Corps as a structural engineer, where he had been accustomed to flood control projects since 1981.

“As the water began to recede, we went out onto the river system to assess the damage caused by the high water for the Rock Island District from Dubuque, Iowa, all the way to Hannibal, Mo.,” said Joers. “Seeing the flood and all the damage it caused made me have a new respect for the river and the power it has.”

Joers said the Corps used machinery that went under the water to assess the damage to structures along the river. In doing so, the Corps saw a lot of damage to storage sheds and control stations. “Crews worked long hours to get sites back up and running so that navigation could operate and go through the locks again,” he added. “Operations were still shut down for a while after the water went down, though.”

After Effects

Many businesses along the Missouri and Mississippi rivers were damaged, and the navigation industry was no exception. Bruce McGinnis, CEO of McNational Inc., said the company’s National Repair & Maintenance division located near Alton, Ill., sustained property damage after 5 feet of floodwater infiltrated its shipyard facilities.

“Back then, I was vice president of operations at all of our locations,” said McGinnis. “My involvement during the flood consisted mostly of controlling our losses at the Alton yard and securing our floating equipment. Our shops were flooded.”

McGinnis, who flew from Dubuque, Iowa, to Cairo, Ill., on the day of the crest, said the flood was an incredible sight that he will never forget. His father, who currently serves as chairman of the company, was heavily involved in overseeing the repairs at the shipyard following the flood. “The flood and everything our yard endured at the time definitely prepared me for future events, which, although unpredictable, are inevitable,” said McGinnis.

Busse echoed a similar sentiment regarding the inevitability of another massive flooding event in the area. “There will always be a bigger flood,” he said. “Some people said that the Flood of 1993 will never happen again. Others have said that it is a 20-year flood now, which is ridiculous, too. You can’t say it will never happen again, because it will.”

Lessons Learned

Back then, Busse said the Corps’ mission did not include conveying risk to the public. “We touted how great our projects were, and they are, but it is now important for us to let people know the risk rivers pose.

Today, he and his colleagues tell younger engineers to not be overconfident in all aspects of their jobs. “People said the levees would hold and then they failed about three hours later,” said Busse. “We must be honest about the risk.”

Today, one of the St. Louis District’s larger undertakings involves the levees at St. Louis on the East side of the bank. After the flood, the Corps prioritized the examination of levees along the river and looked for problem areas. While the levees sustained the flood, Busse said it was crucial that the Corps look for ways to strengthen them so that they will hold up to another major flood.

“I’ll always remember shortly after the river crested on August 1, my boss said that he needed me to look at something,” said Busse. “We walked down to the Gateway Arch, and he said, ‘there’s the river, and you need to see it.’ And then he told me to go home.”

After 120 days working countless hours in the Water Control Office, Busse had hardly seen the flood up close. “I’m glad I saw it,” he said. “Having the opportunity and responsibility for river forecasting and operation of projects that impact flood-fighting efforts has been one of the highlights of my career. I saw what it takes, how long and heavy it must rain and how many agricultural levees have to go under water to make another major flood happen. I don’t think many people in my field today will see that, but it’s not impossible.”

For Joers, one of the biggest lessons the Corps and river stakeholders learned from the flood was how to do a better job of reacting to floods from a maintenance and emergency perspective. “I think the flood was so big at the time, beyond what people imagined, that it affected a lot of things we didn’t think about beforehand,” he said. “Now we think about precautions like putting machinery up higher and doing things in a more cost-effective way. It’s now easier for lock and dam operators to prepare for another flood, as it made everyone think of new design scenarios for looking at high water. Also, whenever the Corps conducts major rehabilitation projects to its facilities, it makes them more flood-proof so that they can get back into operation faster.”