Inland mariners running east of New Orleans are very familiar with Chef Menteur Pass and, a little farther east, the Rigolets. They’re natural passes with strong tidal currents that you have to watch out for.

Not quite a hundred years ago, the new Intracoastal Waterway route actually went through the Rigolets into Lake Pontchartrain. The canal from the Industrial intersection to the Rigolets didn’t exist yet. Intracoastal traffic coming to New Orleans from the Gulf Coast would wiggle its way through the Rigolets, then follow the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain to Seabrook and the brand-new Industrial Canal.

There were no highway bridges at the Rigolets—only a railroad bridge. People who wanted to travel east or north of New Orleans did so by boat or by train.

In the 1920s, automobiles were becoming popular, and there were advocates across the country arguing for improved roads. One of those proposed roads was billed as the Old Spanish Trail, an east-west highway running from Florida, through New Orleans, and on to California. Among the biggest obstacles were the deepwater passes at the Chef and the Rigolets.

In 1910, an early automobile enthusiast made the trek from Pass Christian, Miss., to New Orleans in a Model 10 Buick equipped with acetylene lights, smooth tires, and no windshield. It took 34 hours of actual running time, and three overnights. A guide had to be hired to find the trail across the swamp at Pearl River, watching for the holes and ruts left by teams of oxen. The route from there was not to the Rigolets, but up around the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain to Burnside on the Lower Mississippi River (Mile 170 AHP), then down the River Road to New Orleans. This was considered quite an achievement at the time.

By the 1920s, though, automobiles were becoming more popular, and motorists in New Orleans and on the Mississippi Gulf Coast wanted a more direct connection. At the same time there were advocates all across the country arguing for better roads. One of those proposed roads was billed as the Old Spanish Trail, an east-west highway running from St. Augustine, Fla., through New Orleans, and on to San Diego, Calif. Among the biggest obstacles on this route were the deepwater passes at the Chef and the Rigolets.

New Orleans made a first step by building a halfway decent gravel and clamshell road from downtown out as far as the Chef. There was no bridge there to continue east to the Rigolets, so independent ferry contractors filled the void.

Ferry Services

Automobile ferry service out of Chef Menteur began in September 1921, running around the “island” between the Chef and the Rigolets, then up the Pearl River to the town of Pearlington, Miss. Service was daily, leaving the Chef at 8 a.m. and returning at around 2 p.m. By the following year, there were no fewer than three ferry operators at Chef Menteur, running either to Pearlington or to Slidell, La.

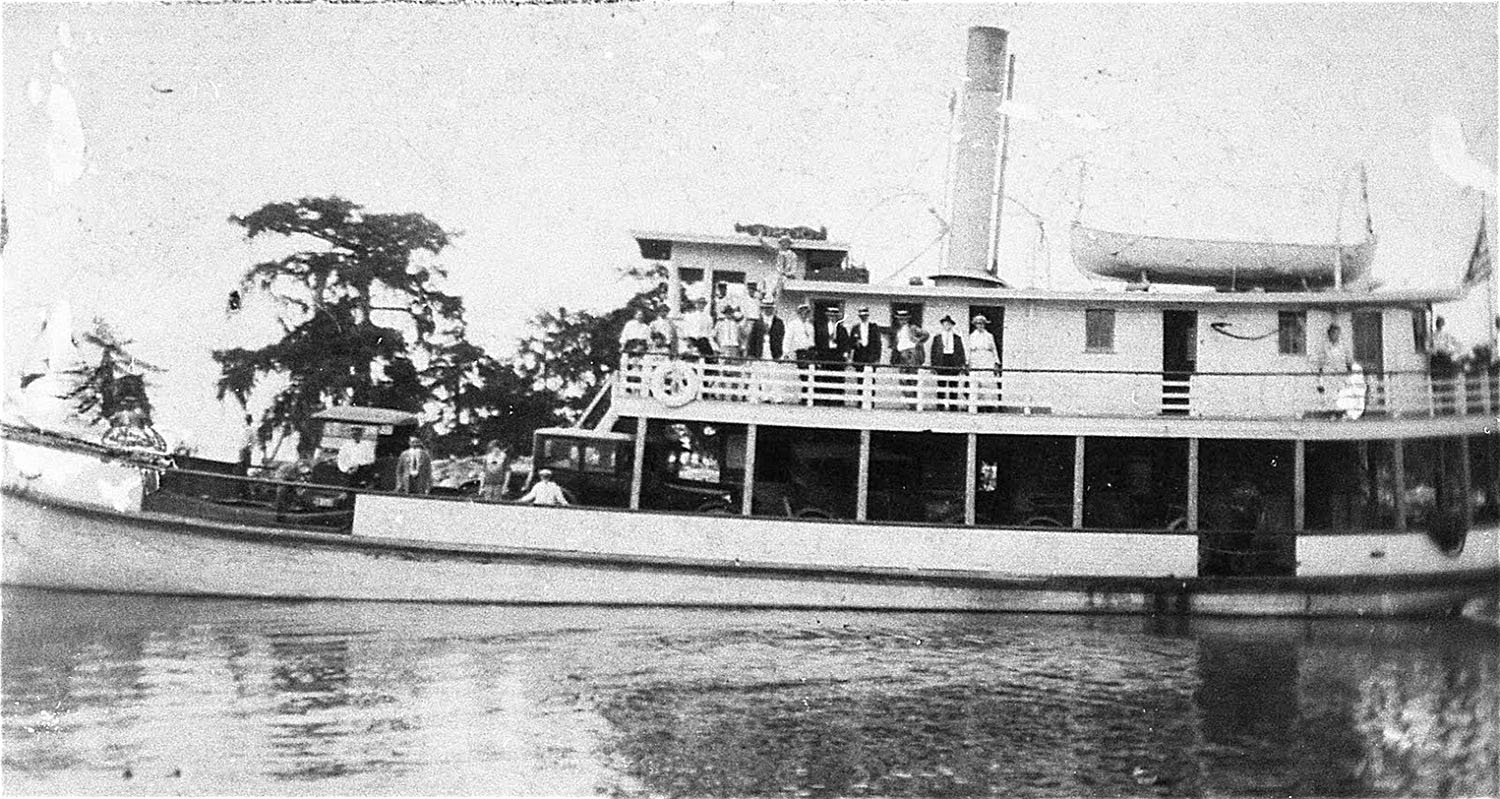

Some of the ferries had the look of large oyster boats, but in fact they were small packet steamers converted to allow the automobiles of the day to drive onto the bow, then along the broad main deck areas on the port and starboard side. The Chef ferries could go south into Lake Borgne, then east toward Pearl River, or instead they could go north into the east end of Lake Pontchartrain, then on to Slidell or Pearlington.

One of the ferry operators was Abner Hursey of Pearlington. He placed the motor vessel Lena M.H. in service in May 1922. It carried four automobiles, and made a single round trip daily.

Things changed in 1925, when a clamshell road was completed from the Chef all the way to the Rigolets. Hursey enlarged his fleet, and offered a ferry crossing at Chef Menteur, plus a fleet of ferries crossing the Rigolets.

The Chef Menteur operation was a steam-powered cable ferry with three cables. One cable pulled the barge-like vessel across the pass, while the other two cables were guides to keep the ferry on course against the strong currents.

Out at the Rigolets, Hursey had quite a fleet, most of them model-bow boats, with no one ferry exactly like the others. The Garibaldi carried 10 cars and about 40 people. The Leta, with a 100 hp. Fairbanks Morse crude oil engine and billed as “the fastest boat of its kind in Southern waters,” carried 12 cars and 50 people. The 84-foot O.S.T., named for the Old Spanish Trail, carried a whopping 30 cars and 200 people.

In 1927, Hursey introduced a brand-new, steel-hull ferry, the Hiway, costing about $50,000 to build. The Hiway could carry 12 cars and 50 people. It actually had a basically square deck like most modern inland automobile ferries.

During these years, the motoring public grew from a minority of enthusiasts to a large segment of the well-to-do population. In addition to business travelers, now there were hundreds of families heading to the Mississippi Gulf Coast to escape the sweltering New Orleans summers, or tourists from the east traveling to New Orleans.

For the increasingly impatient motoring public, the ferries came to be seen as an aggravation. Motorists hoping to catch the Chef and Rigolets ferries on the Fourth of July and other holidays in 1927 sometimes had to wait for hours.

By this time, the state of Louisiana was active in building paved roads, and replacing ferry crossings with bridges. The first highway bridge over the Rigolets, the Watson-Williams toll bridge (which now carries U.S. Route 11) opened for business in February 1928, near where the Rigolets meets Lake Pontchartrain. At that time, it was the longest concrete pile bridge in the world. The Old Spanish Trail became a real express throughway, at least by early 20th century standards.

Less than two years later, the state built a toll-free bridge nearby, along with bridges over Chef Menteur and Pearl River. This route is now part of U.S. Route 90.

Needless to say, the ferries became unnecessary. In 1932, Hursey Transportation Company was bankrupt. Its assets, including not just ferries but tugs and a derrick and six barges, were auctioned off.

In the 21st century, the Rigolets and Chef Menteur Pass are quieter places, marine traffic-wise. Ironically, we now have the 25-mile Rigolets Cut, a straight canal section of the Intracoastal Waterway that would have made a ferry trip out of Chef Menteur quicker and calmer than back in the 1920s.