The Mississippi Valley Engineer Division and the New Orleans Engineer District have granted the conditional permit and Section 408 permission to Louisiana’s Coastal Protection & Restoration Authority (CPRA) for the long-sought-after $2.3 billion Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion on the west bank of the Mississippi River near the community of Ironton in Plaquemines Parish.

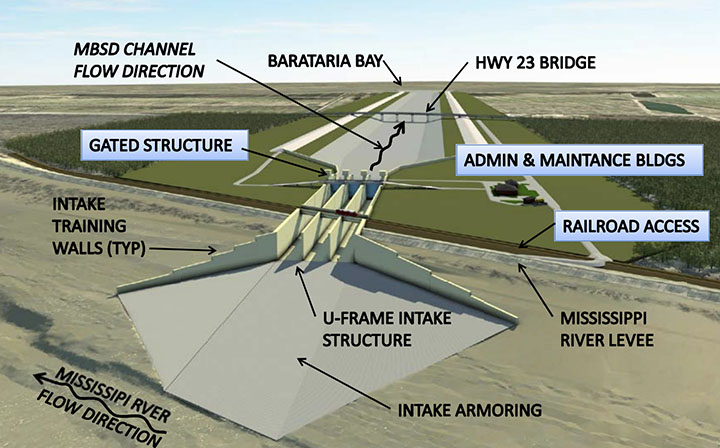

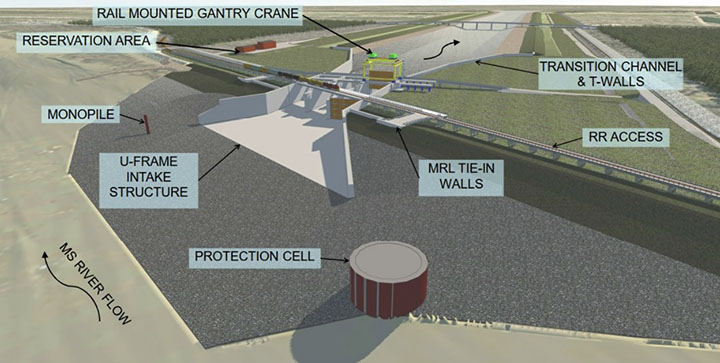

The structure will involve a break in the river levee just above Ironton and a canal extending 2 miles to the southwest and ending in the upper reaches of Barataria Bay. The Barataria region is seeing some of the highest rates of land loss in a state that’s losing about a football field of land every 100 minutes due to subsidence, erosion and relative sea level rise.

The project, though, has been contentious due to the expected negative impacts it will have on marine mammals in the Barataria Basin, on commercial fishing in the area and on navigation in the Mississippi River.

“We take great care to neither endorse nor oppose any project when administering our regulatory authorities,” New Orleans District Commander Col. Cullen Jones said in announcing the record of decision. “Our responsibility is to use the science, engineering, technology and data available to make the best-informed decision.”

According to CPRA’s project overview, the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion will have about a 1,600-foot-wide footprint and a variable discharge capacity of up to 75,000 cubic feet per second (cfs.). The targeted site is at about Mile 69 on the Mississippi River. Besides the cut in the river levee, the project will also require modifications to Louisiana Highway 23 and an existing railroad spur. The structure is expected to discharge about 25,000 cfs. when the river has a flow of 450,000 cfs. at Belle Chasse. That would swell to a maximum of 75,000 cfs. as the river approaches 1 million cfs.

In low-flow conditions, the diversion would operate at up to 5,000 cfs. to “protect, sustain and maintain newly vegetated or recently converted fresh, intermediate, and brackish marshes near the diversion outflow,” according to the project’s Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).

The goal of the diversion is to reconnect the wetlands of Barataria Bay with both freshwater and sediment, which in pre-levee days would have naturally and regularly filtered in from the Mississippi River, building land and supporting freshwater vegetation in the process.

“The large-scale sediment diversion is intended to re-establish the connections between the Mississippi River and the mid-Barataria Basin by transporting sediment, freshwater and nutrients into the mid-Barataria Basin,” Maj. Gen. Diana Holland, commanding general, Mississippi Valley Division, said in the Corps’ announcement. “Public input was a critical part of both permitting processes and was integral to both decisions. The people that live and work in a project area know the area better than anyone. Their concerns and recommendations, along with that of our fellow local, state and federal cooperating agencies, were essential to our evaluation of topics such as the local environment, economics and environmental justice. Every comment received was considered and used in reaching the final decisions.”

Murky Picture For Land-Building

The EIS, though, paints a murky picture both for the projected land-building impacts of the diversion and for coastal Louisiana in general. Construction of the project will result in about a 900 acre net loss of land, with the project having a footprint of 1,376 acres, which will be partially offset by 467 acres of land restored by material moved during construction.

Once in operation, the diversion will build or sustain an estimated 6,260 acres of wetlands over the first 10 years and 13,400 acres by 2070, or just under 21 square miles. Over that same timeframe, though, the Barataria region is expected to continue its rapid loss of land, with acreage built by the diversion accounting for a quarter of remaining wetlands within less than 50 years.

Operation of the diversion is also expected to undermine the wetlands that make up the birdfoot delta near the mouth of the river. The EIS projects a loss of 3,000 acres in the birdfoot delta by 2070, which the study directly attributes to “permanent, moderate, adverse impacts” from the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion. The birdfoot delta is the region below Head of Passes that has seen more than 10,000 acres of land built in just the last decade due to beneficial use of dredged material pumped from the Mississippi River Ship Channel.

Despite those land gain/land loss estimates, Louisiana officials swiftly praised the announcement from the Corps and touted the merits of the project.

“Today is a monumental day for the state of Louisiana,” said Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards. “The Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion is a first-of-its-kind environmental infrastructure project that will exist in our own backyard to serve areas experiencing some of the highest rates of land loss in the world. The project also represents a major step forward to restoring for injuries suffered by our coastal estuaries as a result of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Communities we feared could be removed from the map in 50 years will instead see thousands of acres of wetlands in the future that will provide them with natural and sustainable protection. I commend CPRA, USACE and all other agencies involved for their leadership and diligence throughout this process, resulting in a truly robust analysis and science-based decision.”

CPRA Chairman Chip Kline echoed Edwards’ take on the project.

“Today is the most important day in the history of our state’s coastal program and represents a turning point in the story of Louisiana’s coast,” Kline said in a statement. “The green light on this project moves us closer to finally implementing a critical component of the solution to our land loss crisis that science has pointed us to for decades—using the land-building power of the Mississippi River to sustainably build and maintain land. It unlocks our ability to use every tool in the toolbox, making our approach to coastal restoration and protection efforts stronger, more effective and more innovative than ever before.”

Environmental Costs

The project, though, comes at a cost. Research has indicated the drop in salinity in the Barataria Basin, along with lower water temperatures and an increase in algae blooms, as a result of the diversion will cause “the functional extinctions of dolphins” in the area over time, with only a remnant population remaining in 50 years. The infusion of freshwater is also expected to decimate the shrimp and oyster industries west of the Mississippi River.

And while the EIS found that the project would have a net positive impact of decreasing storm-related surge for west bank communities of the greater New Orleans area, communities in lower Plaquemines Parish, such as nearby Myrtle Grove, are expected to see a potential increase of up to 1.7 feet of storm surge as a result of the diversion. Communities south of the outfall area could also see non-federal levees overtopped, “which would not otherwise be overtopped” without the diversion, the EIS stated.

Impacts To Navigation

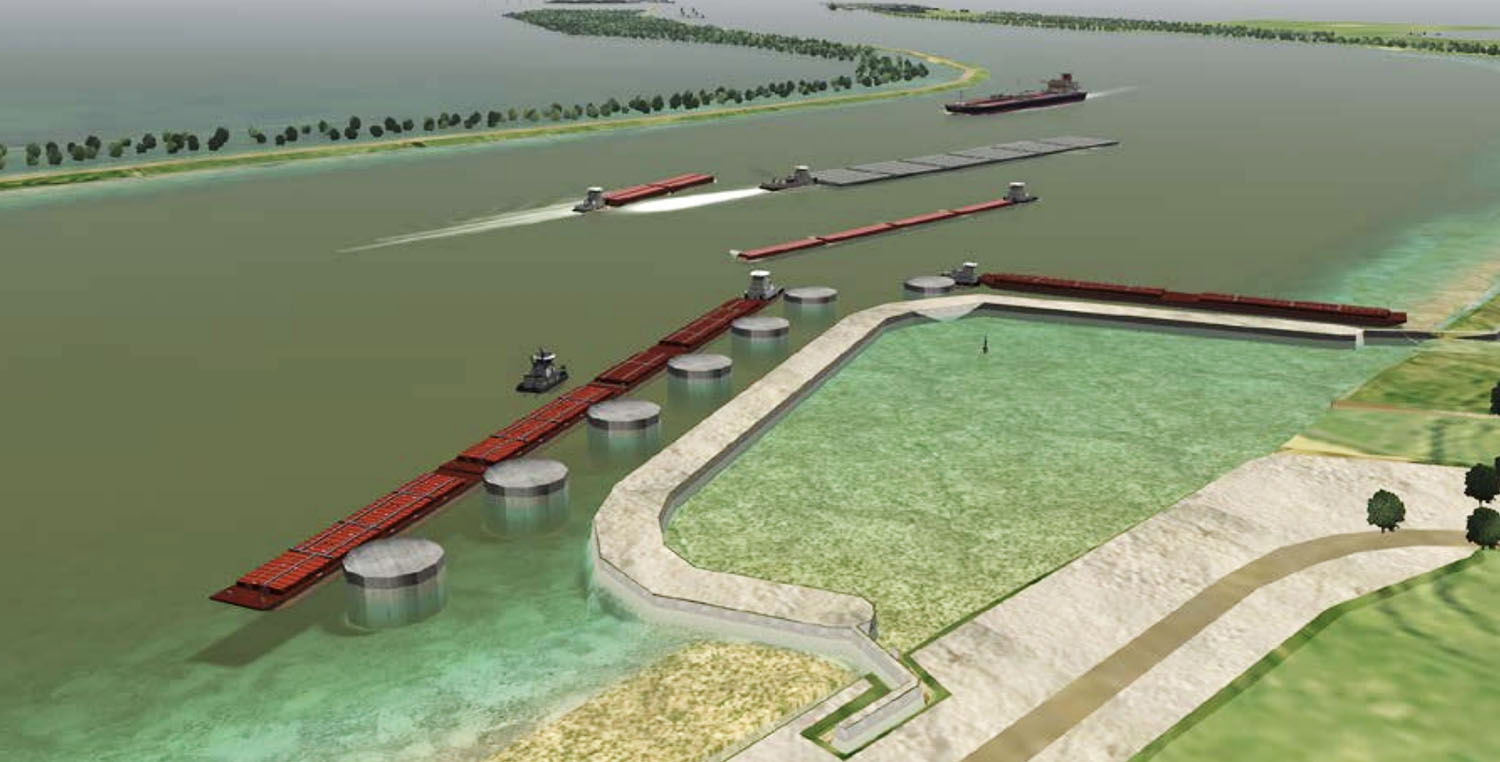

The Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion will have multiple, permanent impacts on navigation in the Mississippi River, the EIS stated. Shallow-draft vessels can expect safety impacts during construction due to the proposed use of a cofferdam for the river intake system. Once operational, crosscurrents at the structure will create “moderate, intermittent but permanent, adverse impacts” for towboats, and “some congestion may be unavoidable and could cause transit delays.”

The project is also expected to cause “minor to moderate, permanent, adverse increases in dredging requirements” for portions of the Mississippi River Ship Channel, both near the structure and below Head of Passes and in Southwest Pass “due to project-induced changes to typical shoaling patterns and locations,” the EIS stated.

Those issues led Capt. Kelly Denning, commander of Coast Guard Sector New Orleans, to voice concerns over the project in a July 22 letter to Col. Stephen Murphy, the former commander of the New Orleans District.

“My staff has reviewed the permit application and met with navigation stakeholders over the previous months to hear their input regarding this project,” Denning said in her July 22 letter. “Based on this information, I have concerns that this project presents an increased risk to navigation safety both during the construction and operational phases of the project, as well as unknown sedimentation impacts to anchorages.”

Less than a month later, though, Denning submitted a second letter, which softened her disposition.

“Based on information obtained from communications with the Coastal Restoration and Protection Authority (CPRA), Coast Guard Navigation Center, and the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) Navigation and Dredging Analysis, the Coast Guard has no objection to this structure’s permit,” Denning said in an August 16 letter to Murphy.

Much of the concern from the navigation industry for the diversion centers on its unknown impact on shoaling in both the channel and anchorages. Navigation advocates have seen that kind of cause-and-effect from a diversion in West Bay, where there’s a break in the riverbank below Venice. The flow in the river slows at West Bay, which has caused shoaling in nearby Pilottown Anchorage.

“In some spots when it’s low river, you can stand up in the middle of the river,” said Capt. Michael Bopp, president of the Crescent River Port Pilots Association. “We’ve lost that anchorage.”

The concern is that the same will happen as a result of the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion.

Bopp made sure to voice his support for CPRA and the agency’s efforts to restore the state’s fragile coastline and wetlands. Bopp said coastal restoration and navigation both come together in projects that involve pumping sediment from the river directly into nearby wetlands. Those projects benefit both the ship channel, and the commerce and jobs it supports, while also restoring wetlands.

“It’s two birds with one stone,” Bopp said. “It accomplishes building land immediately where they’re pumping it. It’s not years in the future.”

And with all the breaks in the riverbank south of Belle Chasse, there’s a fear the reduced flow could put the ship channel in jeopardy.

Sean Duffy, executive director of the Big River Coalition, stated in a comment recorded in the EIS that on a particular day in late May, the flow at Belle Chasse was 776,000 cfs. But with all the outlets and breaks in the riverbank below there—including at the Bohemia Salinity Control Structure (also known as Mardi Gras Pass), Ostrica Lock, Neptune Pass, Fort St. Phillip, Baptiste Collette, Grand (or Tiger) Pass, West Bay, Cubits Gap and Pass A’Loutre—Duffy estimated that the flow in the river had dropped to under 240,000 cfs. by the time it reached Southwest Pass, the outlet for the ship channel.

Had the diversion been in operation that day, Duffy surmised, about 50,000 cfs. would’ve been flowing through it, which would’ve further lowered the flow at Southwest Pass to around 189,000 cfs.

“In doing my best to read over the hundreds of pages in all the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, I see nothing that mentions the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority has studied what flow must be maintained in the ship channel to maintain both commerce and to repel salt water,” Duffy said. “Clearly the loss of stream power along the Mississippi River is troubling and already impacting the navigation industry and the [Corps’] ability and cost to maintain the nation’s most prolific navigation channel.”

Part of the conditional approval from the Corps requires CPRA to “develop safety measures to be implemented during construction and operation” of the structure. CPRA is also held responsible for “identifying and remediating shoals/shoaling caused” by the project. “Remedial measures include dredging,” the conditions state.

Caption for top photo: A simulation of barge and ship traffic passing a cofferdam during construction of the planned Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion on the west bank of the Mississippi River near the town of Ironton, La. (Graphic from final EIS for Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion.)