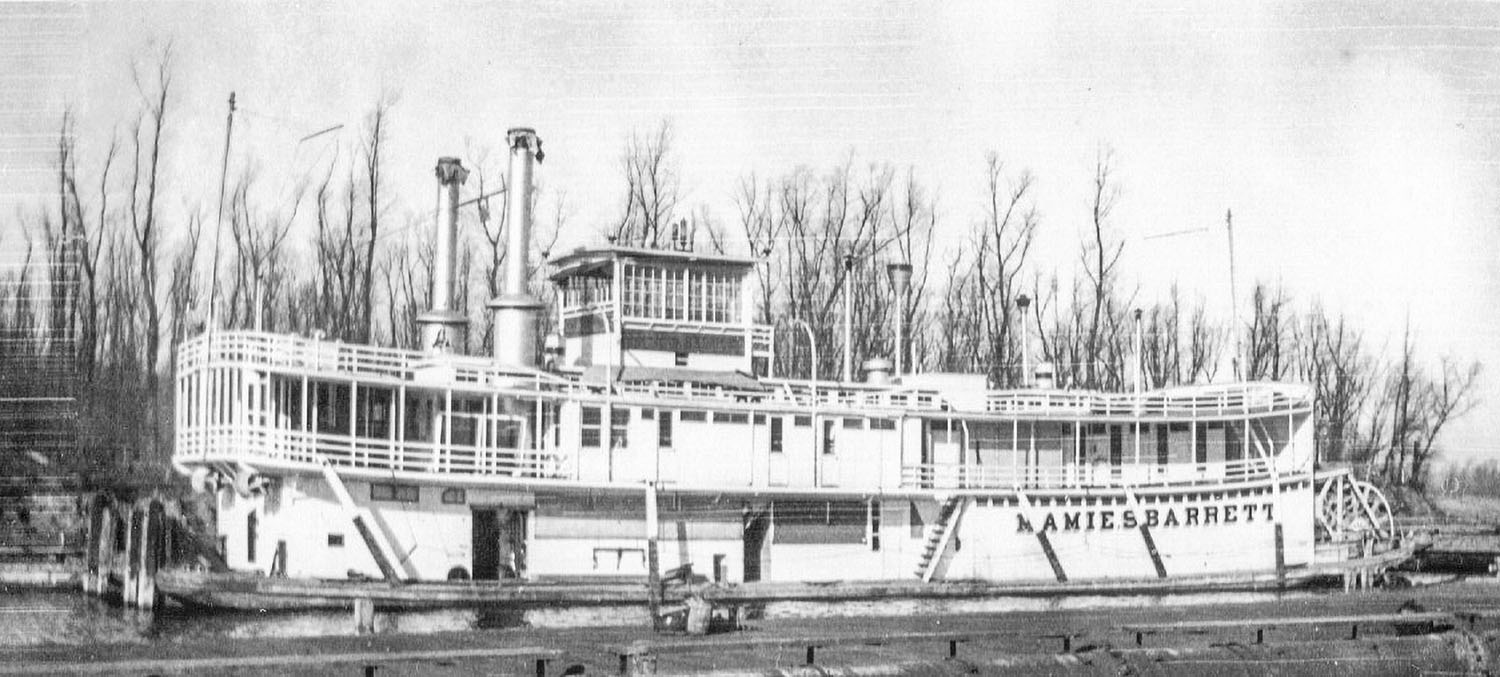

The Mamie S. Barrett was a 1921 product of the Howard Shipyard at Jeffersonville, Ind.

Constructed for Oscar F. Barrett, of Cincinnati, on a steel hull measuring 146 feet in length by 30 feet in width, the towboat was powered by compound, non-condensing engines built by the Barnes Company. Two oil-fired return flue boilers made by Fowler-Wolfe supplied the steam.

Sold to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1923, the sternwheeler was assigned to Florence, Ala. By 1926, the boat was reassigned to the Rock Island District. In 1935, the name of the vessel was changed to Penniman, with Capt. Peter Antrainer long serving as master.

In 1947, the Vollmar Brothers Construction Company at St. Louis bought the retired riverboat and in turn sold it in early 1948 to the Harbor Point Yacht Club, which converted the old steamboat into a marina, restaurant and clubhouse named Piasa at Upper Mississippi River Mile 204.3 in the Alton pool. All of the machinery was removed and one boiler was fashioned into a vertical stand for a lighthouse on the marina property. The staff of The Waterways Journal was invited to attend the festivities for the formal opening.

In 1981, the boat was sold to the Oberle family, who restored the original name and moved it to Eddyville, Ky., on the Cumberland River. By late 1987 the Mamie was purchased by John and Mary Hosemann, who had it towed to Vicksburg, Miss.

After it was opened as a restaurant and showboat theater, this writer and his parents enjoyed lunch in the former engineroom in July 1988, when the Mississippi and Yazoo were at record low stages due to drought conditions. I recall that it was somewhat difficult to keep the dishes and flatware on the table due to the wonderful camber of the hull—and the fact that the stately sternwheeler was barely afloat! Following lunch, Mary Hosemann graciously took us on a tour of the unrestored upper deck and pilothouse, which still contained the pilotwheel, steering levers, lazy bench, bell stand, whistle treadle, station bills, signage, chart rack and even the drinking fountain.

Several years later, the Mamie ceased business at Vicksburg and was towed downriver to a dock at Vidalia, La., opposite Natchez. After a time, the boat disappeared off the radar and nobody seemed to know anything about its whereabouts. I enlisted the aid of my longtime friend Capt. Robert Reynolds, then pilot on the mv. Hal D. Miller of Magnolia Marine Transport Company, to keep an eye out for the elusive steamer. After several years elapsed, Bob phoned with the exciting news that a crew member on his towboat had casually mentioned that, while fishing in the cutoff at Deer Park (17 miles below Natchez), he had seen an old steamboat high and dry on the bank. After further interrogation, it was ascertained that the boat definitely was the missing Mamie.

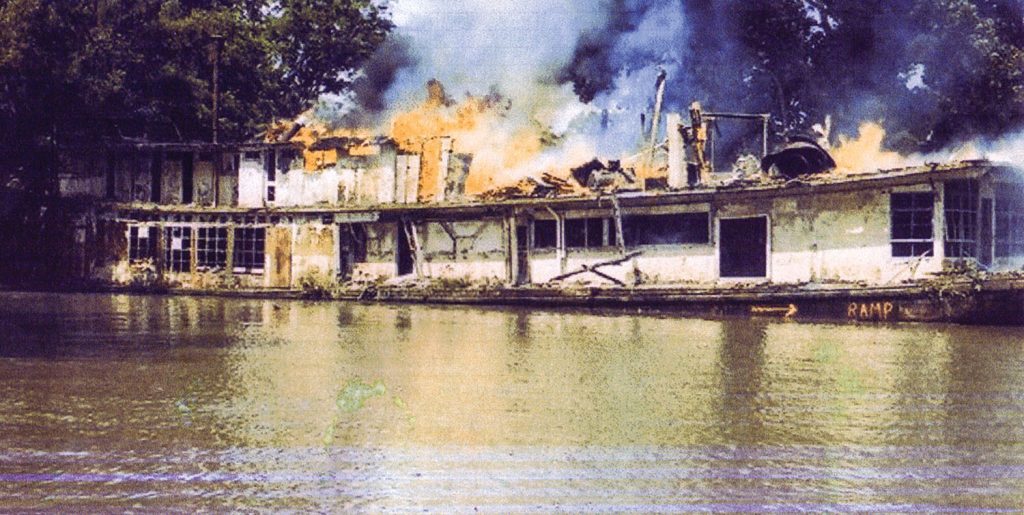

Since 2001, numerous river enthusiasts, including this writer, have made multiple pilgrimages to view and photograph the beached boat at Deer Park, just over the levee from the highway. With the passing of time, the venerable vessel deteriorated drastically with collapsed smokestacks, sagging decks, broken windows, railings and bulkheads. The sternwheel, sans most of its wooden bucket planks, became overgrown with brush and locals admonished visitors to be watchful for snakes aboard the derelict paddlewheeler.

Although there were several parties seriously interested in obtaining the boat for restoration, skyrocketing costs and controversy over legal ownership stymied all attempts. Reportedly, during flooding in 2017, the Mamie floated into nearby power lines, igniting a fire that destroyed the upper deck and pilothouse. Today, all that is left of one of the few extant vessels built by the Howards is the steel remnants, which languish in a Louisiana bayou.

Caption for top photo: The Mamie S. Barrett in winter quarters at Alton Slough in 1934. (Photo by Ruth Ferris; Keith Norrington collection)