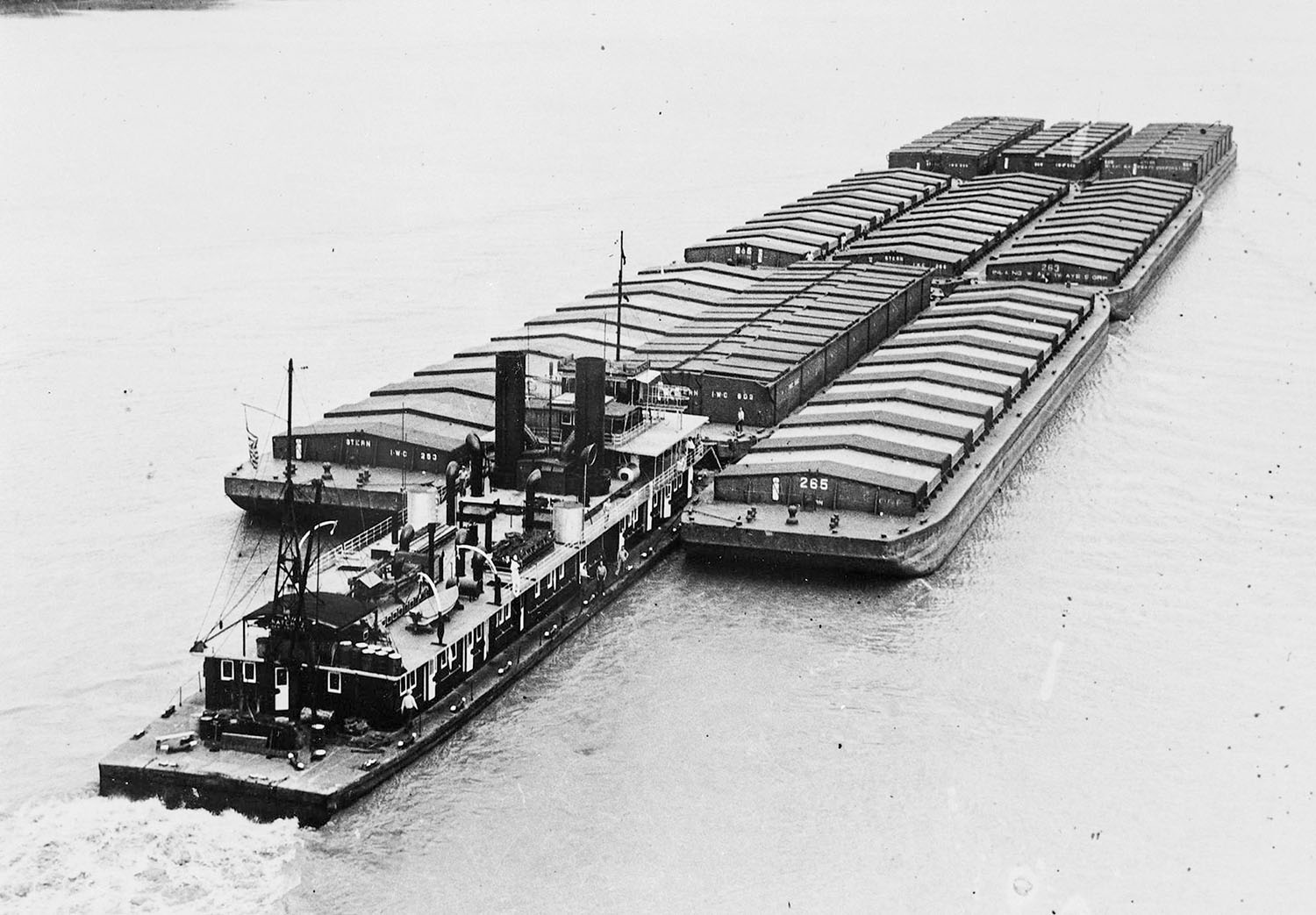

The Inland Waterways Corporation (IWC), the barge line chartered by the U.S. government to revitalize river transportation following World War I, was focused on the task and not bound by tradition. Innovation was sought out and championed. The use of propeller-driven craft was an early experiment, and it was largely successful.

In 1920, the IWC—commonly dubbed the “Federal Barge Line” by river interests—let contracts for six large steam prop towboats. These would all be products of two West Virginia shipyards, with the Marietta Manufacturing Company, Point Pleasant, W.Va., building the Baton Rouge, Cairo, Memphis and St, Louis, while the Charles Ward Engineering Works, Charleston, W.Va., would build the Natchez and Vicksburg.

These boats were identical, with steel hulls 200 by 40 by 7.9 feet, and they had triple expansion condensing engines—15-3/8’s, 26-1/4’s, 44-1/8’s—with a 26-inch stroke and rated 1,800 hp. at 140 rpm. The props were 9 feet, 4 inches in diameter, and the water-tube boilers were fired by oil. The boats were painted a deep green with black trim, and the dark appearance led them to gain the nickname “black” boats. The Ward-built Natchez was the first to come out, and the only one of the group to be completed in 1920.

According to Way’s Steam Towboat Directory, Capt. Cassius C. Woods was an early master of the Natchez, and in 1923 became the IWC superintendent at Memphis. Others to serve aboard as master were Charles E. Moore, Tom Ledger and Billy R. Smith, as well as Capt. Bob Manning, described in Way’s as “graduate of the old wooden coalboat days.” On August 15, 1945, chief engineer Wilson Bragg fell overboard and drowned just above New Madrid, Mo.

The Natchez was upbound below Greenville, Miss., on March 4, 1948, and as the Lower Mississippi was running very swift, the decision was made to double-trip the treacherous Greenville Bridge. Capt. James F. Browinski, master, was on watch as the Natchez started up through the bridge with three loaded oil barges in tow. Just behind the Natchez was the DPC steamer Sohio Latonia, of the Sohio Petroleum Company. In newspaper reports published later, Capt. William A. Howell, master of the Sohio Latonia, told of watching the Natchez first stall out just above the bridge, then turn broadside to the current and capsize as it struck one of the bridge piers.

Capt. Walter I. Hass was the off-watch pilot of the Natchez and had come to the pilothouse just before the boat overturned. In a published report, he told of Capt. Browinski struggling to get the boat and tow straight with the current again and how just before the boat contacted the pier he heard Browinski exclaim, “I HAVE to come ahead on her!” As the boat began to roll, Hass went out a pilothouse door and literally climbed down the side of the cabin and hull of the boat as it turned over. Having grabbed a life ring from a handrail, he made it to shore. Fourteen of the crew were not so fortunate and perished, including Capt. Browinski, chief engineer Keith A. Montgomery and second engineer Charles Jarvis.

In addition to the Sohio Latonia, the Casablanca of American Barge Line and Irene Chotin of Chotin & Pharr participated in the rescue of survivors.

When I went to work for Ashland Oil in 1985, Joe Thomas of Mt. Vernon, Ind., was chief engineer of the Tri-State. He had been a young deckhand on the Sohio Latonia, witnessed the Natchez sinking and helped with recovering survivors. The event was etched in his memory, especially since two of those initially rescued died aboard before they could be transferred to a medical facility. Thirteen survivors were taken to a Greenville hospital, and the tragedy was widely reported in newspapers across the country, including the New York Times. This was the greatest loss that the IWC would ever experience, and the only one of this class of boat to be lost. The Natchez, having sunk in deep water, was never recovered. Oil stains from ruptured fuel tanks remained on the bridge pier for many years.

The sister vessels to the Natchez operated for the IWC largely without major incidents. The Memphis sank at Brownsville, Minn., in May 1950, but it was raised. It is interesting that some photos of the Memphis show it with Mississippi Valley Barge Line markings on the stacks, yet neither Way’s or the Inland River Record show any owner or operator other than IWC.

The IWC interests were sold in 1953 to Herman Pott/St. Louis Ship, who aptly named the company Federal Barge Lines. This class of vessels, along with several other IWC steamers, were then promptly dismantled. The Cairo hull, with cabins removed, became a part of the Merdie Boggs & Sons facilities at Catlettsburg, Ky., where it was utilized for barge cleaning and repair for many years before finally being scrapped.

Caption for photo: The Natchez with tow. (Dan Owen Boat Photo Museum collection)