The Ohio River valley, along with much of the Mississippi River system, recently went through winter storm Fern, which dumped several inches of snow in the upper regions, freezing rain and ice from Texas to Tennessee and a mix of it all everywhere else. In the middle of this mess were the dedicated boat crews, working line haul and harbor towboats, as well as grocery and supply delivery personnel that had to deal with the elements.

Weather is something that those who work the rivers have had to deal with down through time.

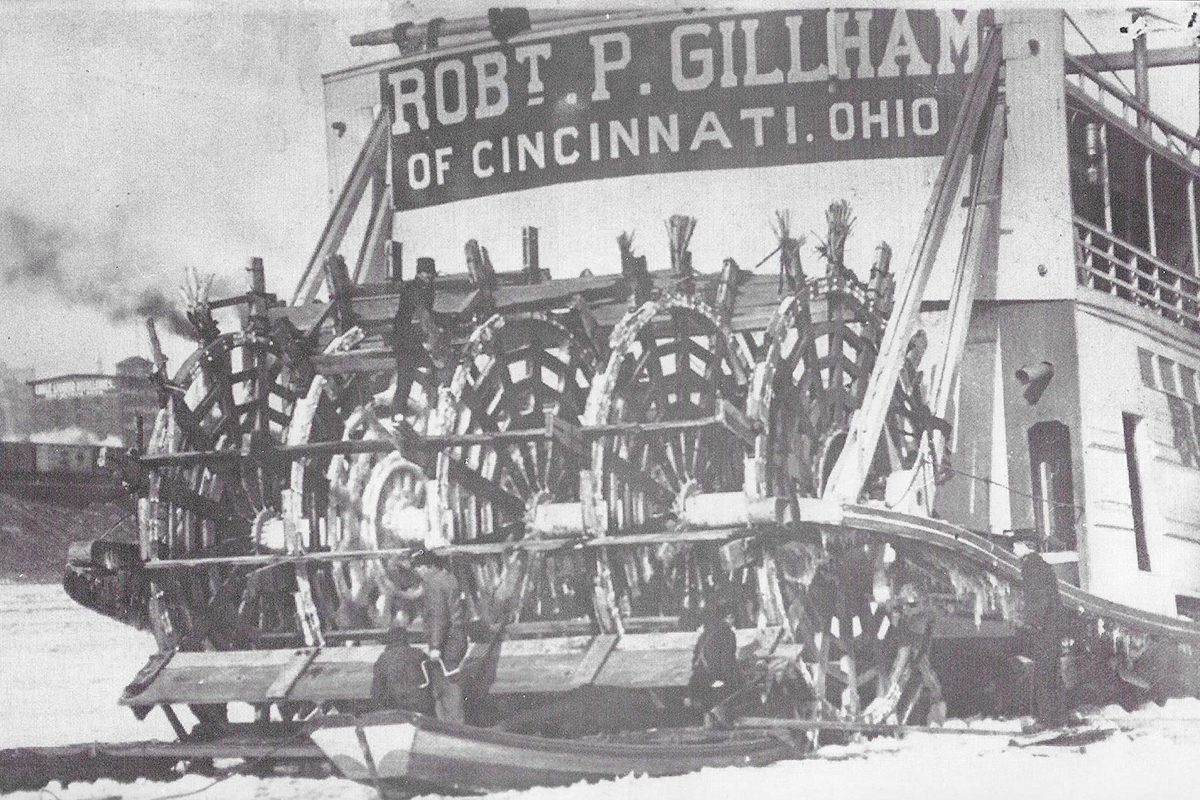

The first photo is of the business end of the steam sternwheel towboat Robert P. Gillham (shown as “Robt. P. Gillham on the stern). The sternwheel has obviously come in contact with heavy ice. There are at least five men shown in the photo working on the wrecked sternwheel, and judging from the amount of damage, they will have a long, labor-intensive and bitterly cold task ahead of them, working with only hand tools.

The Gillham was built in 1901 at Parkersburg, W.Va., for the Campbell’s Creek Coal Company. Its wood hull measured 149.5 feet by 31.5 feet and had compound engines with 14-inch high pressure cylinders, 24-inch low pressure cylinders (14’s, 24’s) and a 7-foot stroke. The Gillham towed Kanawha River coal to Cincinnati and Louisville, Ky., and earned the rather dubious nickname among the crew as the “Rob ’em, Starve ’em, Kill ’em.” This photo was taken at some point prior to 1925, when the boat was renamed Henry C. Yeiser Jr. at the time that Campbell’s Creek merged into the Hatfield interests.

Wooden hulls such as the one on the Gillham were very susceptible to damage by heavy ice. The “big ice” of 1918 saw many wood hull steamboats cut down and destroyed, including the celebrated sidewheelers City of Louisville and City of Cincinnati, large packets owned by the Louisville & Cincinnati Packet Company to run between those two cities. The City of Louisville, built by Howard at New Albany, Ind., in 1894 had a wood hull that was 301 feet by 42.7 feet and Frisbie engines with 30-inch cylinders and a 10-foot stroke. Soon after entering service, it set a record time of nine hours, 42 minutes running from Louisville to Cincinnati. That record stands to this day. For many years afterward, it carried a sign on each side of the pilothouse stating “9-42.”

The City of Cincinnati, also built by Howard a few years later in 1899, was slightly smaller, with a wood hull measuring 300 feet by 38 feet and engines with 26-inch cylinders and a 10-foot stroke. On January 20, 1918, the Ohio River was frozen over and gorged up in places. The two big boats were moored at Cincinnati when a gorge broke loose, and the ice started moving. Both had their wooden hulls crushed, and they sank. Photos of the City of Louisville capture it fighting valiantly with steam up, smoke coming from the stacks and side wheels turning, to no avail.

Even in the era of steel hulls, ice conditions are challenging to operate in. Barges and boat hulls can be holed. Deck crew can spend miserable hours tending portable pumps on leaking barges, keeping them fueled up and running so that the barge doesn’t sink, and the pumps don’t freeze up. Once icing gets too thick, traffic may be forced to find the safest place possible to tie the tow off and wait for conditions to improve. The waiting isn’t much easier on the crew since the circumstances warrant constant vigilance.

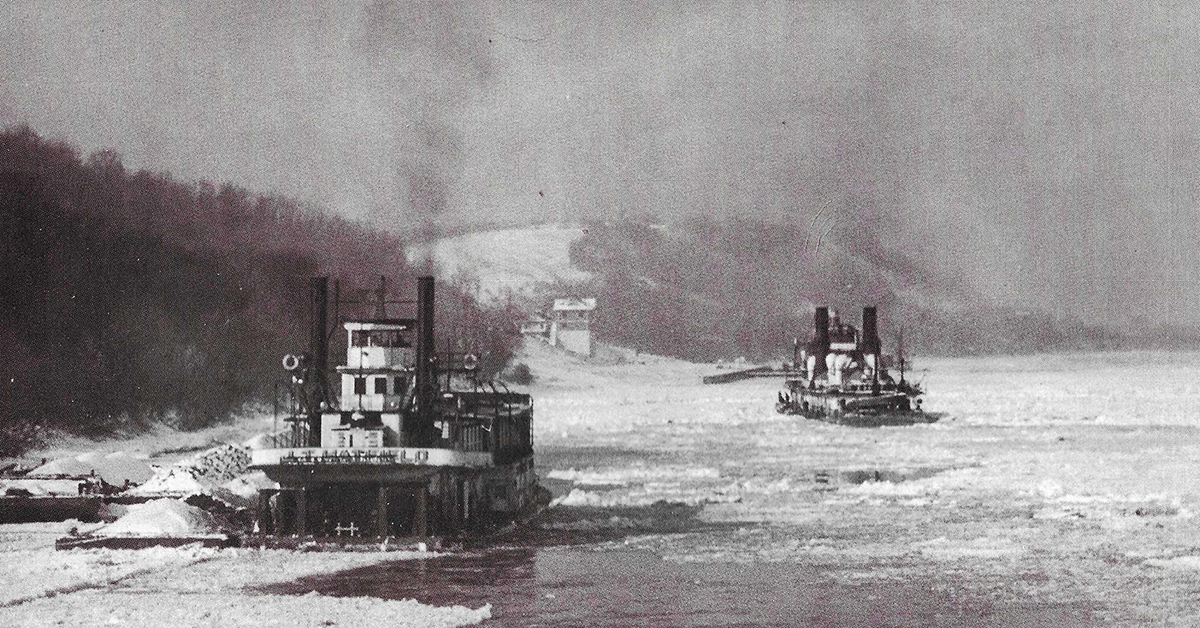

The second photo depicts some boats stopped in heavy icing above old Lock 35 on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River just below New Richmond, Ohio. The boat lying outside the coal tow is the steam sternwheel J.T. Hatfield, originally built as the General Ashburn at Dubuque, Iowa, in 1927 for the Inland Waterways Corporation. It was sold to the Hatfield-Campbell’s Creek Coal Company in 1941. This photo can be somewhat dated by the fact that it was renamed J.T. Hatfield in 1945. It had a steel hull that was 130 feet by 35 feet and was fitted with condensing engines, 15’s, 30’s with 6.5-foot stroke rated 600 hp.

The Hatfield was a stoker-fed coal burner, and visible in the picture is where the crew has been digging in the coal pile of the barge. The crew would transfer the coal to the boat to keep the furnaces fed. As mentioned before, standing by and waiting for the ice to clear was not easy duty. The boat in the distance easing down on the lock is the Mississippi Valley Barge Line’s Louisiana, built in 1930 by Ward at Charleston, W.Va., as a steam prop oil burner, with a steel hull measuring 191 feet by 40.6 feet. It may have been going to the lock to make a crew change, call the office or check on the weather report.

Even in “modern” times, ice has been an issue. Mule training, where a boat pushes one barge while pulling others in a single string behind was very prevalent on the Illinois River. Understandably, some damage to the boat could occur. Several years ago, I was upbound on the Upper Mississippi River below St. Louis. The Sugarland, then owned by Scott Chotin Inc. and considered by many to be the most attractive retractable pilothouse boat ever built, was up ahead, and another vessel radioed to make arrangements to overtake it. A while later, the second boat radioed the Sugarland again to say he didn’t know what was going on but that he wasn’t catching them anymore. The fellow on the Sugarland laughed and said that he had an idea what had happened.

“We just got out of the shipyard from having the stern transom rebuilt after it was beat up on the Illinois last winter, and now, every time a barge gets within a half mile of that pretty new stern, she takes off like a rocket!”

Here’s hoping that all crewmembers can stay as safe and warm as possible throughout the present weather conditions.

Featured image caption: The steamers J.T. Hatfield (left) and Louisiana in heavy ice above old US Lock 35 on the Ohio River in the late 1940s. (Photo from the Jerry Sutphin collection)